The Geology of New Zealand

February 25, 2010

New Zealand is home to one of the broadest collections of geological features on the planet, all packed densely across an area the size of Colorado. For geologists who want to see their field in action—without having to drive across an entire continent—New Zealand is the place to go.

"It's a small country, but in some ways it's also a huge country," Associate Professor of Geosciences Tim D. Cope says. "There is so much topography there that if you were to flatten New Zealand out, it would be a whole lot bigger than it looks on a map."

During Winter Term 2010, Cope and Professor of Geociences James G. Mills led a group of students on a tour of New Zealand's geological highlights. With Cope and Mills driving the group's two 15-passenger vehicles, outings started early and lasted most of the day, ending each night at the next hostel on the itinerary. Cope first organized the tour while he was a graduate student at Stanford University. Since then, many of the sites, such as Mount Ngauruhoe—an active volcano better known to many as Mount Doom—were made internationally famous by the Lord of the Rings films.

During Winter Term 2010, Cope and Professor of Geociences James G. Mills led a group of students on a tour of New Zealand's geological highlights. With Cope and Mills driving the group's two 15-passenger vehicles, outings started early and lasted most of the day, ending each night at the next hostel on the itinerary. Cope first organized the tour while he was a graduate student at Stanford University. Since then, many of the sites, such as Mount Ngauruhoe—an active volcano better known to many as Mount Doom—were made internationally famous by the Lord of the Rings films.

"Whenever people saw our big bus of Americans drive up, if it was one of the filming sites they assumed we were on a Lord of the Rings tour," Cope says.

Director Peter Jackson likely chose New Zealand as a filming location not only because he's a native, but also because of the country's incredible geological diversity. Separated by only a narrow stretch of the Cook Strait, the country's North and South Islands are the product of entirely different tectonic phenomena.

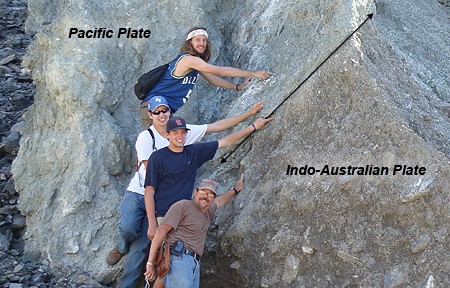

Beneath the North Island, the Pacific tectonic plate is being forced under the Indo-Australian plate, forming a chain of volcanoes where molten rock reaches the surface above. This sort of volcanic activity can occur on land or underwater depending on where the plates meet. The group took a day trip to White Island, an active marine volcano off the North Island's coast, named for the cloud of steam that rises from it. There, students were constantly reminded of forces beneath their feet. White Island erupted as recently as July 2000, and its seeping sulfur gas and acidic crater lake warrant the use of gas masks, hard hats and careful steps.

Beneath the North Island, the Pacific tectonic plate is being forced under the Indo-Australian plate, forming a chain of volcanoes where molten rock reaches the surface above. This sort of volcanic activity can occur on land or underwater depending on where the plates meet. The group took a day trip to White Island, an active marine volcano off the North Island's coast, named for the cloud of steam that rises from it. There, students were constantly reminded of forces beneath their feet. White Island erupted as recently as July 2000, and its seeping sulfur gas and acidic crater lake warrant the use of gas masks, hard hats and careful steps.

"[White Island] made me feel so small and insignificant, but I loved it," says Christina M. Wildt ‘13. "The fact that we have no control over the awesome powers that are shaping the world is what really turned me on to geology."

On the South Island, the Pacific and Indo-Australian plates collide, pushing the Southern Alps nearly four kilometers high at a geologic pace of 1.1 centimeters per year. The group hiked along glaciers that formed in the South Island's high altitude, carving their way to sea level through a temperate rainforest.

Because of the different type of tectonic convergence on the South Island, it's possible to place a hand on outcroppings of both massive plates at the same time (pictured above). Cope argues that being able to touch and walk among the lessons taught in the classroom is a key part of an education in geology.

"You can't learn science without a laboratory," Cope says. "Chemists have a chemistry lab; we have the planet. In a sense, this is a laboratory exercise where students are able to get their hands on the science."

Cope's students agree. Wildt and Christopher D. A. Taljan '13, both freshmen, took an introductory geology course during their first semester on campus to prepare for the trip. They returned from New Zealand impressed at how much they had learned in three weeks.

"To try and identify a certain rock, or to point out a given geologic structure is so much harder in the field, but so much more rewarding than it is in the classroom," Taljan says. "It helps you notice the differences between two rocks that could be easily identified as the exact same thing."

"It made a huge difference to be able to actually see and touch the geologic features that we learned about in class," Wildt says. "I thought I understood everything that I learned in our Earth and the Environment course, but I realized after I was in New Zealand that you can't really understand geology fully unless you experience it in the field."

Back