#113 = Volume 38, Part 1 = March 2011

N. Katherine Hayles

Material Entanglements: Steven Hall’s The Raw Shark Texts as Slipstream Novel

In Bruce Sterling’s short but provocative essay delineating the “slipstream” genre, he characterizes it as “a contemporary kind of writing which has set its face against consensus reality ... [and] which simply makes you feel very strange; the way that living in the late twentieth century makes you feel, if you are a person of a certain sensibility.” Although he does not say more about why late-twentieth-century living should make one feel strange, I suggest that a strong reason is the growing power, pervasiveness, and hiddenness of databases. Databases of every kind now populate digital media, from the vast and deep data of the Internal Revenue Service to the broad-reaching data of the Department of Defense and the secret files of the National Security Agency, not to mention commercial databases of large corporations such as Walmart, Microsoft, and Chase Bank, as well as myriad other information systems on which virtually every academic, social, and economic institution depends. Indeed, so important are databases to contemporary society that Lev Manovich has suggested they are the dominant cultural form, displacing the long-standing priority of narrative (212-43). Their tremendous influence notwithstanding, most of these databases are invisible to the general public, which either does not have access to them or, in best-case scenarios, is able to search them but not to see their internal structures. This is the “consensus reality” of late-twentieth- and twenty-first- century life in developed countries.

The creepiness of knowing that one’s everyday transactions depend on invisible databases suggests an obvious point of intervention for contemporary novels: subverting the dominance of databases and re-asserting the priority of narrative fictions. Steven Hall’s remarkable first novel The Raw Shark Texts (2007) creates an imaginative world that performs the power of written words and reveals the dangers of database structures. The narrative begins when Eric Sanderson, the protagonist, says “I was unconscious. I’d stopped breathing” (3). As he fights for life and breath, he realizes that he knows nothing about who he is; all of his memories have mysteriously vanished. The backstory is related through letters he receives from his former self, “The First Eric Sanderson,” who tells him he is the victim of a “conceptual shark,” the Ludovician, that feeds on human memories and hence the sense of self. As the Second Eric Sanderson journeys to discover more about his past, the text explores what it would mean to transport a (post)human subjectivity into a database, at the same time that it enacts the performative power of imaginative fiction conveyed through written language.

Before discussing the moves through which the text performs this extrapolation, I will recapitulate the contrasts between narrative and database. Analyzing database structures, Alan Liu identifies the crucial move as “the separation of content from material instantiation or formal presentation” (216; emphasis in original). Liu points out that contemporary web pages typically draw from backend databases and then format the information locally with XML tags. This separation of content from presentational form allows for what Liu sees as the imperatives of postindustrial information—namely, that discourse be made transformable, autonomously mobile, and automated. He locates the predecessor technologies in the forms, reports, and gauges of John Hall at Harpers Ferry Armory and the industrial protocols of Fredrick Winslow Taylor. While these early prototypes may seem on their faces to be very different from databases and XML, Liu argues that they triggered “the exact social, economic, and technical need for databases and XML” (222; emphasis in original) insofar as they sought to standardize and automate industrial production.

The shift from modern industrialization to postindustrial knowledge work brought about two related changes. First, management became distributed into different functions and automated with the transition from human managers to database software. Second, content became separated not only from presentational form but also from material instantiation. Relational databases categorize knowledge through tables, fields, and records. The small bits of information in records are recombinable with other atomized bits through search queries carried out in such languages as SQL. Although database protocols require each atom to be entered in a certain order and with a certain syntax, the concatenated elements can be reformatted locally into a wide variety of different templates, web pages, and aesthetics. This reformatting is possible because when they are atomized, they lose the materiality associated with their original information source (for example, the form a customer fills out recording a change of address). From the atomized bits, some sequence can then be re-materialized in the format and order the designer chooses.

As Liu argues, postindustrial knowledge work, through databases, introduced two innovations that separate it from industrial standardization. By automating management, postindustrial knowledge work created the possibility of “management of, and through, media,” (224), which leads in turn to the management of management, or what Liu calls “metamanagement” (227). The move to metamanagement is accompanied by the development of standards and, governing them, standards of standards. “The insight of postindustrialism,” Liu writes, “is that there can be metastandards for making standards” (228). Further, by separating content from both form and materiality, postindustrial knowledge work initiated variable standardization: standardization through databases, and variability through the different interfaces that draw upon the databases (234). This implies that the Web designer becomes a “cursor point” drawing on databases that remain out of sight and whose structures may be unknown to him. As Liu summarizes:

Where the author was once presumed to be the originating transmitter of a discourse ... now the author is in a mediating position as just one among all those other managers looking upstream to previous originating transmitters—database or XML schema designers, software designers, and even clerical information workers (who input data into the database or XML source document). (235)

Let us now compare the postindustrialized knowledge work of databases to narrative fiction. Whereas data elements must be atomized for databases to function efficiently, narrative fiction embeds “data elements” (if we can speak of such) in richly contextualized environments of the phrase, sentence, paragraph, section, and story as a whole. Each part of this ascending/descending hierarchy depends on all the other parts for its significance and meaning, in feedback and feedforward loops called the hermeneutic circle. Another aspect of contextualization is the speaker (or speakers), so that every narrative utterance is also characterized by viewpoint, personality, and so forth. Moreover, narrative fictions are conveyed through the material instantiations of media, whether print, digital, or audio. Unlike database records, which can be stored in one format and imported into a completely different milieu without changing their significance, narratives are entirely dependent on the media that carry them. Separated from their native habitats and imported into other media, literary works become, in effect, new compositions, notwithstanding that the words remain the same, for different media offer different affordances, navigational possibilities, and so forth.1

In contrast to databases whose elements may be concatenated in any order, narratives are linear in the sense that one word follows another in syntactical order, and sequential in the sense that one section follows another. Narratives are sensitively dependent on the order of narration; change the order of sections, and a new narrative emerges, even though the words in each section may remain the same. Finally, narratives are temporally encoded. Since the order of narration is crucial to a fiction’s meaning, temporality becomes a prominent means by which narratives achieve significance, as a number of narrative theorists have shown (see Genette and Ricoeur). These contrasts set the stage for my discussion of the strategies by which The Raw Shark Texts instantiates and performs itself as a print fiction—strategies that imply a sharp contrast between narrative and database, especially in light of the standardizations that have made databases into the dominant form of postindustrial knowledge work.

Two Different Kinds of Villains. As Jessica Pressman points out, a major villain in the text, Mycroft Ward, personifies the threat of data structures to narrative fiction.2 Mycroft Ward, a “gentleman scientist” (199) in the early twentieth century, announced that he had decided not to die. His idea was as simple as it was audacious: through a written list of his personality traits and “the applied arts of mesmerism and suggestion” (200; emphasis in original), he created “the arrangement,” a method whereby his personality was imprinted on a willing volunteer, a physician named Thomas Quinn devastated by the loss of his wife. On his deathbed, Ward transferred all his assets to Quinn, who then carried on as the body inhabited by Ward’s self. His experiences in World War I impressed upon him that one body was not enough; through accident, warfare, or other unseen events, it could die before its time. Ward therefore set about to standardize the transfer procedure, recruiting other bodies and instituting an updating process (held on each Saturday) during which each body shared with the others what it had learned and experienced during the week. In addition, in order to strengthen the desire for survival, Ward instituted an increased urge toward self-preservation. This set up a feedback loop such that, each time the standardizing process took place, the result was a stronger and stronger urge for survival. In the end, all other human qualities had been erased by the two dominant urges of self-protection and expansion, making Ward a “thing” rather than a person. By the 1990’s,

the Ward-thing had become a huge online database of self with dozens of permanently connected node bodies protecting against system damage and outside attack. The mind itself was now a gigantic over-thing, too massive for any one head to contain, managing its various bodies online with standardizing downloads and information-gathering uploads. One of the Ward-thing’s thousands of research projects developed software capable of targeting suitable individuals and imposing “the arrangement” via the internet. (204)3

The above summary takes the form of a nested narrative, one of many that pepper the main story. This one is narrated by Scout, the Second Eric’s companion, herself a victim of an internet attack by the “Ward-thing” to take over her body. Saved only because her younger sister pulled out the modem cord to make a phone call, Scout is aware that some small part of her is inhabited by the Ward-thing, while the online database contains some small part of her personality. She is alive as an autonomous person because she fled her previous life and now lives underground in the “un-space” of basements, cellars, warehouses, and other uninhabited and abandoned places that exist alongside but apart from normal locales. The precariousness of her situation underscores the advice that the First Eric Sanderson gives to his successor: “there is no safe procedure for [handling] electronic information” (81; emphasis in original).

The qualities Liu identifies as the requirements to make postindustrial information as efficient and flexible as possible—namely transformability, autonomous mobility, and automation—here take the ominous form of a posthuman “thing” that needs only to find a way to render the standardizing process more efficient in order to expand without limit, until there are a million or billion bodies inhabited by Mycroft Ward, indeed until the world consists of nothing but Mycroft Ward, a giant database hidden from sight and protected from any possible attack.4 Ward in this sense becomes the ultimate transcendental signified, which Liu (following Derrida) identifies as “content that is both the center of discourse and—precisely because of its status as essence—outside the normal play or (as we now say) networking of discourse” (217). At that terminal point, there is no need for stories, their function having been replaced by uploading and downloading standardized data.

Whereas traditional narrative excels in creating a “voice” that the reader can internalize, with the advent of databases the author no longer crafts language so that it seems to emanate from the words on the page. Rather, the author-function is reduced to creating the design and parameters that give form to content drawn from the databases. As Liu points out, the situation is even worse than reducing the author function to a “cursor position,” for the “origin of transmission in discourse network 2000 is not at the cursor position of the author. Indeed, the heart of the problem of authorship in the age of networked reproduction is that there is no cursor point” (235-36), only managers downstream of invisible databases that dictate content. This threat to the author’s subjectivity (and implicitly to the reader’s) is dramatically apparent in the significantly named Mr Nobody, one of Ward’s node bodies.5 When the Second Eric is invited to meet with Nobody, he first finds a confident, well-dressed man working on a laptop. As the conversation proceeds, however, Nobody becomes increasingly disheveled and drenched in sweat until “liquid streamed off him into small brown pools around the legs of his chair,” (143), a description that reinforces the role water and liquidity play in the text. At one point he turns away from Eric and begins conversing with an invisible interlocutor: “It’s too long, the weave has all come apart—loose threads and holes, he’s showing through, you know how it gets just before the pills” (143; emphasis in original). Scout later holds up the confiscated pill bottles, marked with such labels as “CONCENTRATION,” “REASONING,” “STYLE” (177). “This is him,” she comments. “The closest thing to a him there was anyway. This is what was driving the body around instead of a real self” (178). She continues, “He wasn’t really a human being anymore, just the idea of one. A concept wrapped in skin and chemicals” (178).

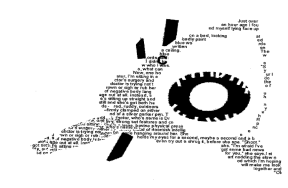

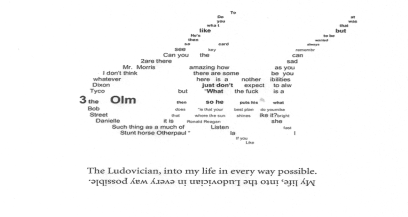

Whereas Ward represents the complete separation of form and content (node bodies versus online database), the text’s other major villain, the Ludovician shark, embodies the complete fusion of form and content. Graphic and verbal representations of the “conceptual shark” depict it as formed through the collapse of signifier and signified into one another. Shown as a graphic, the shark’s body is composed of words and typographical symbols (see Figure 1). Moreover, the text that forms the body changes from image to image, making good the premise that the shark’s flesh forms from the memories he has ingested (in Figure 1, some of the text seems to refer to memories that could have belonged to the First Eric).

Figure 1: Graphic representing Ludovician shark as comprised of words

Represented verbally, the shark combines the morphology of an actual shark with flesh comprised of ideas, language, and concepts, as shown in this passage when Eric and Scout are being pursued by the Ludovician:

Less than fifty yards behind us and keeping pace, ideas, thoughts, fragments, story shards, dreams, memories were blasting free of the grass in a high-speed spray. As I watched, the spray intensified. The concept of the grass itself began to lift and bow wave into a long tumbling V. At the crest of the wave, something was coming up through the foam—a curved and rising signifier, a perfectly evolved fin idea. (158)

Such descriptions create homologies between action in the diegesis, the materiality of the shark as it appears within the story and the materiality of the marks on the page.

A further transformation occurs when not just the shark, but the surrounding environment, collapses into a conceptual space that is at once comprised of words and represented through words on the page. Illustrative is the striking scene when the Second Eric is attacked by the shark in his own home, and suddenly the mundane architecture of floor and room gives way to a conceptual ocean:

The idea of the floor, the carpet, the concept, feel, shape of the words in my head all broke apart on impact with a splash of sensations and textures and pattern memories and letters and phonetic sounds spraying out from my splashdown.... I came up coughing, gasping for air, the idea of air. A vague physical memory of the actuality of the floor survived but now I was bobbing and floating and trying to tread water in the idea of the floor, in fluid liquid concept, in its endless cold rolling waves of association and history. (59)

The Dangerous Delights of Immersive Fiction. Pressman rightly notes that the entanglement of print mark with diegetic representation insists on the work’s “bookishness,” a strategy she suggests is typical of certain contemporary novels written after 2000 in reaction to the proclaimed death of print. Here, fear rather than necessity is the mother of invention; she proposes writers turn to experimental fiction to fight for their lives, or least the life of the novel. Discussing the Ludovician shark, she likens its devouring of memories to a fear of data loss (and to Alzheimer’s disease). In addition to these suggestions, I think something else is going on as well, a pattern that emerges from the way depth is handled in the text. The shark is consistently associated with a form that emerges from the depths; depth is also associated with immersion—for example in Eric’s “splashdown” in his living room and his later dunking when he goes hunting for the shark.

This latter episode, which forms the narrative’s climax, follows the plot of Jaws (1975) almost exactly. Like Jaws, the climax is non-stop, heart-pounding action, arguably the clearest example in the text of what is often called “immersive fiction” (see, e.g., Mangen). The link between the acts of imagination that enable a reader to construct an English drawing room or a raging ocean from words on the page is, in mise-en-abyme, played out for us within the very fiction upon which our imaginations operate. Scout and Trey Fidorous, the man who will be the guide to locate and attack the Ludovician, put together the “concept” of a shark-hunting boat, initially seen as an eccentric conglomeration of planks, speakers, an old printer, and other odds and ends laid out in the rough shape of a boat. “It’s just stuff,” Fidorous comments, “just beautiful ordinary things. But the idea these things embody, the meaning we’ve assigned to them in putting them together like this, that’s what’s important” (300). While Scout and Fidorous create the assemblage, Eric’s task is to drink and be refreshed by a glass full of paper shards, each with the word “water” written on them. At first he has no idea how to proceed, but emerging from a dream in which he falls into shark-infested waters, he suddenly senses that his pant leg is wet—moistened by water spilled from the overturned glass. With that, torrents of water flood into the space, and the flat outline of the boat transforms into an actual craft floating on the ocean. Rubbing “a hand against a very ordinary and very real railing,” Fidorous tells him that the boat “is the current collective idea of what a shark-hunting boat should be” (315). Hovering between believing in the scene’s actuality and seeing it as the idea of the scene, Eric is advised by Fidorous, “It’s easier if you just accept it” (317). With that, the scene proceeds in immersive fashion through the climax.

What is the connection between immersive fiction and immersion in dangerous waters inhabited by a memory-eating shark? At the same time that the text defends the aesthetic of bookishness, it also presents fiction as a dangerous activity to be approached with extreme care. In the one case, we see the strongly positive valuation the author places on the printed book; in the other case, the valuation is more ambivalent or perhaps even negative. Nevertheless, the two align in attributing to fiction immense powers to bring a world into being. The most dramatic testimony to fiction’s power comes when the Second Eric finds the courage to enter the upstairs locked room in the house he inhabits/inherits from his predecessor. Inside is a red filing cabinet, and in the top drawer, a single red folder with a typed sheet that begins “Imagine you’re in a rowing boat on a lake,” followed by evocative details that are the stock in trade of immersive narratives. Then the narrative commands,

Stop imagining. Here’s the real game. Here’s what’s obvious and wonderful and terrible all at the same time: the lake in my head, the lake I was imagining, has just become the lake in your head....

[T]here is some kind of flow. A purely conceptual stream with no mass or weight or matter and no ties to gravity or time, a stream that can only be seen if you choose to look at it from the precise angle we are looking from now....

[T]ry to visualize all the streams of human interaction, of communication. All those linking streams flowing in and between people, through text, pictures, spoken words and TV commentaries, streams through shared memories, casual relations, witnessed events, touching pasts and futures.... This waterway paradise of all information and identities and societies and selves.... (54-55)We know from Fidorous that conceptual fish, including the Ludovician, evolved in the information streams that have, during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, reached unprecedented density and pervasiveness (although the Ludovician is an ancient species). The passage continues with an ominous evocation of the shark’s appearance:

know the lake; know the place for what it is ..., take a look over the boat’s side. The water is clear and deep.... Be very, very still. They say life is tenacious. They say given half a chance, or less, life will grow and exist and evolve anywhere.... Keep looking and keep watching (55).

The lake, then, is a metonym for both fiction and the shark, a conjunction that implies immersive narratives are far from innocent. It is no accident that Eric, after reading the text quoted above, experiences the first attack by the Ludovician in his living room.

Why would fiction be “terrible” as well as wonderful, and what are the deeper implications of double-valued immersion? Like the shark, immersive fictions can suck the reader in. In extreme cases, the reader may live so intensely within imagined worlds that fiction comes to seem more real than mundane reality—as the characters of Emma Bovary and Don Quixote testify. A related danger (or benefit?) is the power of fiction to destabilize consensus reality, as in the narrator’s pronouncement in Gravity’s Rainbow (1973) that “It’s all theatre” (3). Once certain powerful fictions are read, one’s mental landscape may be forever changed (this happened to me when I first encountered Borges’s fictions). Recalling Henri Lefebvre’s proclamation that social practices construct social spaces, narrative fiction is a discursive practice that at once represents and participates in the construction of social spaces. Through its poetic language, it participates in forging relationships between the syntactic/grammatical/semantic structures of language and the creation of a social space in which humans move and live, a power that may be used for good or ill. No wonder the First Eric says of his evocation of a fictional lake, quoted above, that this text is “‘live’ and extremely dangerous” (69).

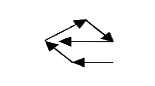

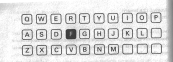

Countering the dangers of immersive fiction is the prophylaxis of decoding. To imagine a scene, a reader must first grasp the text through the decoding process of making letters into words, words into narratives. Reading an immersive fiction, the fluent reader typically feels that the page has disappeared or become transparent, replaced by the scene of her imagination. In The Raw Shark Texts, this process is interrupted and brought into visibility through elaborate encoding protocols, notably with the First Eric’s flashback narratives. The first such narrative arrives in a package that includes a video of a light bulb flickering on and off in a dark room, accompanied by two notebooks, one full of scribbles, the other a handwritten text. The letter explaining the package says that the on-off sequences of the flickering bulb are sending a message in Morse code, the letters of which are transcribed into one of the notebooks. The decoding does not stop there, however, for the Morse code letters are further encrypted through the QWERTY code (see Figure 2). Locate each Morse code letter on a standard

Figure 2: QWERTY decryption method

typewriter keyboard, the letter instructs; note that it is surrounded by eight other letters (letters at the margins are “rolled around” so they are still seen as surrounded by eight others). One of the eight is then the correct letter for a decrypted plaintext, with the choice to be decided by context.

This decryption method is tricky, for it means that one needs a whole word before deciding if a given letter choice is correct. Not coincidentally, it also emphasizes the dependence of narrative on context and sequential order. Whole paragraphs must be decrypted before the words comprising them may be considered correct, and the entire narrative before each of the paragraphs can be considered stable. The reader is thus positioned as an active decoder rather than a passive consumer, emphasized by the hundreds of man-hours required to decrypt the “Light Bulb Fragments.” These textual sections, purporting to be the plaintexts of the encodings, recount the adventures of the First Eric with his girlfriend Clio Ames on the Greek island of Naxos.

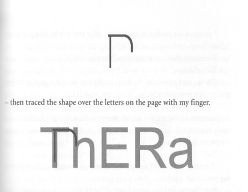

The decoding does not end there, however, for Fidorous points out to Eric that encoded on top of the QWERTY code is yet another text, encrypted through the angular letters formed by the vector arrows that emerge from the direction the decoding took from one QWERTY keyboard letter to another (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Double encryption through vectors formed from QWERTY letters

This text, entitled “The Light Bulb Fragment (Part Three/Encoded Section),” begins “Everything is over” (410), with the First Eric narrating the denouement following Clio’s death while scuba diving. Since the double encryption begins with the very first series of letters in the first “Light Bulb Fragment,” the tragic end of the First Eric’s time with Clio is written simultaneously with the beginning, a fantastically complex method of double writing that pays tribute to the complex temporalities for which narratives are justly famous.

These encodings-within-encodings represent not only protection against immersion but protection against the Ludovician as well. Writing serves two opposite functions in the text. On the one hand, it is part of the stream of information from which the Ludovician evolved and through which it catches the scent of Eric Sanderson (First and Second) as it pursues him. On the other hand, as fiction, it also can be used to disguise Eric’s trail and protect against the Ludovician, as can other written documents such as letters, library books, and so on. As the First Eric explains, “Fiction books also generate illusionary flows of people and events and things that have never been, or maybe have only half-been from a certain point of view. The result is a labyrinth of glass and mirrors which can trap an unwary fish for a great deal of time” (68). Nested narratives, because of their complexity, are especially effective. The First Eric says he has an “old note” claiming “that some of the great and more complicated stories like the Thousand and One Nights are very old protection puzzles, or even idea nets by which ancient people would fish for and catch the smaller conceptual fish” (68). In addition to encoding and encryption, also effective as protection are material objects associated with writing or covered by writing. When they are pursued by the Ludovician coming up through the grass, Scout gives Eric a “letter bomb” composed of old typewriter keys and other such metal shards to throw at the creature. “The explosion sends metal letters—all their associations, histories, everything—blasting out in all directions to scramble the flow the shark is swimming in,” she explains (166). The resulting delay in the shark’s pursuit enables them to reach “un-space.”

If social spaces are formed through social practices, as Henri Lefebvre asserted, then the social practice that both creates and names un-space is writing. The deeper Scout and the Second Eric penetrate into it, the more books, telephone directories, and writing of all sorts emerge as the built environment providing protective camouflage. Their goal is Fidorous’s lair, the entrance to which is constructed as a tunnel in which “everything, everything had been covered in words, words in so many languages. Scraps flapped against me or passed under my crawling wrists covered in what I vaguely recognized as French and German, in hard Greek and Russian letters, in old fashioned English with the long ‘f’s instead of ‘s’s and in Chinese or Japanese picture symbols” (225). Indeed, even the map through the tunnel comes in the form of a word, “ThERa,” a Greek island in the Cyclades chain that includes Naxos. As Scout and the Second Eric wend their way through the tunnel, they “read” the word not through linguistic decoding but through embodied movement, feeling in their knees and hands the turns that take them from the top of the “T” to the loop of the “a” (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: “Thera” as embodied mapTheir embodied transversal emphasizes that writing/reading is not only a semiotic encoding/decoding but a material practice as well. In contrast to the dematerialization that occurs when data are separated from their original instantiations, entered as database records, and re-instantiated as electronic bits, inscriptions on paper maintain a visible, even gritty materiality capable of interacting directly with human bodies.

The Raw Shark Texts as a Distributed Media System. However much it celebrates “bookishness,” The Raw Shark Texts cannot avoid its embeddedness in a moment when electronic databases have become the dominant cultural form. Along with strategies of resistance, the novel also slyly appropriates other media, including digital media, for its own purposes, instantiating itself as a distributed textual system. At the center of the system is the published novel, but other fragments are scattered across a range of media platforms, including short texts at various internet sites, translations of the book in other languages, and occasional physical locations. The fragments that have been identified so far are listed at “The Red Cabinet,” a page on an online forum site devoted to Steven Hall. The effort involved in identifying the fragments changes the typical assumption that a reader peruses a novel in solitude. Here the quest for understanding the text, even on the literal level of assembling all its pieces, requires the resources of crowd sourcing and collaborative contributions.

Elsewhere on this forum site, under the general rubric of “Crypto-Forensics,” Hall himself notes that “[f]or each chapter in The Raw Shark Texts there is, or will be, an un-chapter, a negative. If you look carefully at the novel you might be able to figure out why the un-chapters [are] called negatives.” This broad hint may direct us to the text’s climax, when the action becomes most immersive. As the narrative approaches the climax, an inversion takes place that illustrates the power of fiction to imagine a spatial practice undreamed by geographers: space turns inside out. The text’s trajectory from the mundane ordinary space in which the Second Eric awakes, the actual locations in England to which he journeys,6 the “un-spaces” of underground tunnels and protective architecture of written materials he discovers, and finally the imaginative space of the mise-en-abyme of the shark boat and the ocean on which it floats, may in retrospect be seen as an arc that moves the novel’s inscribed spaces further and further from consensus reality. The spatial inversion that occurs at the climax is the fitting terminal point of this arc.

The inversion comes when Eric, carrying a postcard with a picture of Naxos, discovers that the original picture has been mysteriously replaced by a picture of his house. When he experimentally tries thrusting his hand inside the picture, the image starts to come to life, with cars whizzing and birds flying by. He realizes he has an opportunity to return home via this route but refuses to go back to a safe but mundane reality. With that, the picture changes again, to the brightly colored tropical fish the First Eric had retrieved from Clio’s underwater camera after she died and then had thrown down a dark hole in a foundation. “Something huge happening here. Something so, so important” (422), the Second Eric thinks. Earlier, when he had a similar sensation, he had thought about a coin that has lain in the dirt, one side up, the other down for years; then something happens, and it gets reversed. “The view becomes the reflection and the reflection the view,” he muses (392).

This sets the scene for our understanding of the “negatives.” They represent alternative worlds in which the reflection—the secondary manifestation of the view—becomes primary, while the view becomes the secondary reflection. The point is made clear in the negative to Chapter 8. Found in the Brazilian edition and available only in Portuguese, it presents as letter 175 from the First Eric. Translated by a contributor to the collective forum project, the letter says in part,

I have dark areas on my mind. Injuries and holes whose bottom I can’t see, no matter how hard I try. The holes are everywhere and when you think about them, you can’t stop thinking about them. Some holes are dark wells containing only echoes, while others contain dark water in their depths. Inside them I can see a distant full moon, and the silhouette of a person looking back at me. The shape terrorizes me. Is it me down below? Is it you? Maybe it isn’t anyone. The view becomes a reflection and ... something more, something else.

Evocative of the lake scene in which the dark water becomes the signifier for the emergence of the Ludovician, the phrase that the First Eric cannot quite complete is fully present in the Second Eric’s thoughts in the novel: “The view becomes the reflection, and the reflection the view.” Simply put, the negatives represent an alternative epistemology that from their perspective is the view, but from the perspective of the “main” narrative represents the reflection.

A cosmological analogy may be useful: the negatives instantiate a universe of anti-matter connected to the matter of the novel’s universe through wormholes. The parallel with cosmology is not altogether fanciful, for in the “undexes” (indexes on “The Red Cabinet” page that reference the semantic content of the negatives), one of the entries is “Dr Tegmark,” a name that repeats at the novel’s end in the phrase “Goodby Dr Tegmark” (426). The reference is to Max Tegmark, an MIT physicist who has written several popular articles about parallel universes. On his web site, entitled “The Universes of Max Tegmark,” the scientist has commented:

Every time I’ve written ten mainstream papers, I allow myself to indulge in writing one wacky one.... This is because I have a burning curiosity about the ultimate nature of reality; indeed, this is why I went into physics in the first place. So far, I’ve learned one thing in this quest that I’m really sure of: whatever the ultimate nature of reality may turn out to be, it’s completely different from how it seems. So I feel a bit like the protagonist in the Truman Show, The Matrix or The 13th Floor trying to figure out what’s really going on. (emphasis in original)

The speculative nature of Tegmark’s “wacky” articles and his intuition that consensus reality is not an accurate picture is represented in the novel through the wormhole that opens in the print text when Eric puts his hand in the photograph. The fact that mundane reality is now the “reflection” (relative to his viewpoint) implies that he is now in an alternative universe, one that is somehow definitively different from the place where he began.

What are the differences, and how are they represented within the text? We can trace the emergence of this alternative universe through the Second Eric’s journey into un-space. In addition to wending deeper into the labyrinths of written material that lead to Fidorous, Eric experiences a growing attraction to Scout and an intuition that somehow Scout is not only like Clio but, in a “ridiculous” thought that won’t leave him alone, actually is Clio mysteriously come back from the dead (303). This, the deepest desire of the First Eric, is why he let the Ludovician shark loose in the first place. The Second Eric discovers a crucial clue in the bedroom that the First Eric occupied in Fidorous’s labyrinth; he finds an Encyclopedia of Unusual Fish containing a section on “The Fish of Mind, Word and Invention” (263-64).The section refers to an “ancient Native American belief that all memories, events and identities consumed by one of the great dream fishes would somehow be reconstructed and eternally present within it” (265; emphasis in original). Shamans allowed themselves to be eaten by the shark, believing that in this fashion “they would join their ancestors and memory-families in eternal vision-worlds recreated from generations of shared knowledge and experience” (265; emphasis in original). Reading about this practice, the First Eric evidently resolved to seek Clio in a similar fashion, a venture that implies the existence of a vision-world in which they could be reunited and live together.

Negative 1 is the Aquarium Fragment, which presents as the prologue to The Raw Shark Texts. Alluded to in Chapter 7 (63),it narrates the backstory to the First Eric’s quest. An extra page inserted into the Canadian edition contains the fragment’s cover image and title page describing it as “a limited edition lost document from THE RAW SHARK TEXTS by Steven Hall.” In pages numbered -21 to -6 (since this is a negative, the numbers would logically go from the more negative to the less negative as the narrative moves forward), the First Eric recounts entering the Aquarium, an underground un-space that contains row after row of neglected fish tanks. He finds the tank containing the Ludovician, “the last one in captivity,” his guide Jones tells him. In front of the tank sit three old men, each looking at the man on his left while furiously scribbling on a pad of paper. Finding one of the pages, Eric reads a description of a man’s face in minute detail, recounted in one long run-on sentence that, Jones tells him, runs through all the files in the room. “Direct observation. Always in the present tense, no simile, analogy, nothing remembered or imagined. No full stops. Just only and exactly what they see when looking at the man to their left, in a continuous and ongoing text” (-8). Eric understands that this writing functions as a “non-divergent conceptual loop,” a kind of verbal feedback system that constitutes the shark’s cage. Significantly, this is a form of writing that abjures any fictionalizing, any act of the imagination. Walking into the space, Eric experiences a “horrific clarity” that “came into the world, a sense of all things being exactly what they were.... I turned slowly on my heels; all three men were staring straight at me. All things filled with relevance, obviousness and a bright four-dimensional truth” (-8).

It is in this state that Eric sees the Ludovician, “partly with my eyes, or with my mind’s eye. And partly heard, remembered as sounds and words in shape form. Concepts, ideas, glimpses of other lives or writings or feelings—” (-7). There follows a graphic of the kind seen in the main text, of a shark comprised of words, which Eric perceives as “swimming hard upstream against the panicking fast flow of my thoughts” (-7). After another, larger-sized graphic (because the shark is getting closer), there follows the sentence, “The Ludovician, in my life in every way possible,” followed by the upside-down and inverted sentence, “My life, into the Ludovician in every way possible” (-6). The mirror inversions of the sentence across the horizontal plane and vertical axis function as the wormhole that allows the reader to traverse from the alternative universe of the negative back to the “main” narrative of the print novel (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Image at the end of “The Aquarium Fragment”The “negative” prologue is essential for understanding the logic behind the Second Eric’s intuition that Scout is Clio, as well as for the denouement in which Eric and Scout swim toward Naxos, presumably to re-enter the idyllic life the First Eric shared there with Clio. This is, of course, an impossible desire—to bring someone back from the dead and enjoy once again the life one had before the beloved’s death. As an impossible desire, this wish is deeply tied up with the Ludovician and what the “conceptual shark” represents. As we have seen, the Ludovician is constituted through a feedback loop between signifier and signified, mark and concept. As theorized by Saussure, the mark and concept are two sides of the same coin, two inseparable, although theoretically distinct, entities. In re-writing Saussure, Jacques Lacan changed the emphasis so that the concept (or signified) faded into insignificance and the major focus was on the play of signifiers in infinite chains of deferrals, a process arising from what Lacan described as “the incessant sliding of the signified under the signifier” (419). Lacan theorized that the chain of signifiers was linked with the deferral of socially prohibited desire, specifically desire for the mother. Because desire, to exist as such, implies lack, the chain of signifiers is driven by a logic that substitutes a secondary object for the unattainable object of desire, a substitution displaced in turn by another, even more distanced object of desire, and so on in an endless process of deferrals and substitutions. Language as a system instantiates this logic in the play of signifiers that can never be definitively anchored in particular signifieds—i.e., a system of “floating signifiers.”

What if language, instead of sliding along a chain of signifiers, was able to create a feedback loop of continuous reciprocal causality such that mark and concept co-constituted each other? Such a dynamic differs from Saussure, because there is now no theoretical distance between mark and concept; it also differs from Lacan, because the signified not only re-enters the picture but is inextricably entwined with the signifier. Contravening Lacan’s logic of displacement, the result might be to enable an impossible desire to be realized, albeit at a terrible cost, since it is precisely on the prohibition of desire that, according to psychoanalytic theory, civilization and subjectivity are built. The Ludovician represents just this opening and this cost: Clio is restored in Scout, but at the cost of annihilating the First Eric’s memories and therefore his selfhood. When the wormhole opens for the Second Eric, he has the choice of re-entering the universe in which impossible desire can be satisfied or returning to his quotidian life, in which case the Scout-Clio identification would surely disappear, if not Scout herself. When he decides to remain in the universe of the reflection rather than the view, he traverses the wormhole and comes out on the other side.

The mutual destruction of the Ludovician and Mycroft Ward occurs when the two inverse signifiers (the complete separation of form and content in Ward and their complete fusion in the Ludovician) come into contact and cancel each other out in a terrific explosion, an event the text repeatedly compares to matter and anti-matter colliding (246, 318). With that, the wormhole closes forever, and the cost of Eric’s choice is played out in the denouement. In a move that could never be mapped through database and GIS technology, the narrative inscribes a double ending.

The first is a newspaper clipping announcing that the dead body of Eric Sanderson has been recovered from foundation works in Manchester. Allusions to the Second Eric’s journey echo in the clipping; for example, the psychiatrist making the announcement is named “Dr Ryan Mitchell,” the same name Eric encountered in the “Ryan Mitchell mantra” used to ward off the first attack of the Ludovician. The repetition of names implies that his journey through un-space has been the hallucinogenic rambling of a psychotropic fugue (the condition with which Eric’s psychiatrist, Dr Randle, had diagnosed him). Extensive parallels support this reading, suggesting that Eric has taken details from his actual life and incorporated them into his hallucination. In this version, the distinction between the First and Second Eric is understood as an unconscious defense mechanism to insulate Eric from the pain of Clio’s loss. For example, Eric recounts in the double-encoded section that his anguish is exacerbated by late-night phone calls from Clio’s father blaming him for her death, with the phone rings represented as “burr burr, burr burr” (412). In the shark-hunting episode, the shark’s attack on the boat is also preceded by “burr, burr” (418), presumably the sound of the creature rubbing against the boat’s underside. Similarly, the foundation in which Eric’s body is found corresponds with the “deep dark shaft” (413) in which the First Eric threw Clio’s fish pictures. The image is repeated in the (hallucinated) dark hole into which the First Eric descended to find the Ludovician, and the “dark wells” that the First Eric perceives in his memory in Negative 8. This reading is further supported by a clever narrative loop in which the Second Eric starts writing his life’s story with a magical paintbrush given him by Fidorous, beginning with “I was unconscious. I’d stopped breathing” (286; emphasis in original), a move that locates the entirety of the Second Eric’s narration within his hallucination.

The other version takes the Second Eric’s narrative as “really” happening. This reading is reinforced by a postcard Dr Randle receives a week after Eric’s body is found announcing that “I’m well and I’m happy, but I’m never coming back,” signed “Eric Sanderson” (427). The card’s obverse, shown on the next page (428), depicts a frame from Casablanca (1942) in which the lovers are toasting one another, a moment that in this text is literally the last word, as if to contravene the film and insist that happy endings are possible after all. Also reinforcing this reading is the reader’s investment in the Second Eric’s narrative. To the extent a reader finds it compelling, she will tend to believe that the Second Eric is an authentic subjectivity in his own right.

The undecidability of the double ending makes good the novel’s eponymous pun on “Rorschach Tests.” Like an inkblot, the double ending inscribes an ambiguity so deep and pervasive that only a reader’s unconscious projections and conscious inclinations can give it final shape. This ambiguity highlights another way in which narrative differs from database: its ability to remain poised between two alternatives without needing to resolve the ambivalence. In the fields of relational databases, undetermined or unknown (null) values are anathema, for when a null value is concatenated with others, it renders them null as well. In narrative, by contrast, undecidables enrich the text’s ambiguities and make the reading experience more compelling, precisely because both endings are supported by textual evidence and so rendered undecideable.

Conclusion. In defining slipstream, Sterling characterized it as a genre that “has set its face against consensus reality,” which aligns it with some aspects of the cognitive estrangement characteristic of science fiction. At the same time, Sterling’s differentiation of it from both sf and the mainstream positions the genre somewhere in the middle, partaking of both its parents while never exactly aligning with either. Many sf novels play with the notion of a hallucinogenic fantasy that either becomes, or at least cannot be distinguished from, consensus reality—for example, Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Lathe of Heaven (1971), Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game (1985), and Greg Egan’s Quarantine (1992). Some cyberpunk texts have featured plots very similar to Hall’s, with a lurking online presence offering a psychological or even physical threat, such as John Varley’s story “Press Enter■” (1985) or Pat Cadigan’s novel Synners (1991). In this respect, The Raw Shark Texts is at least as much science fiction as it is mainstream. What it contributes to the slipstream genre is a quality it shares with many contemporary mainstream novels but that is very rare in sf: an involvement with its materiality as a verbal object made of words created by ink marks durably impressed on paper. The feedback loops it instantiates between the text as diegetic narrative and as material object gives its imaginative world a conceptual depth and a materio-semiotic vibrancy that make it exemplary of what slipstream can accomplish.

In addition, The Raw Shark Texts provides us with a parable for our times. Narrative is undoubtedly a much older cultural form than database (especially if we consider databases as written forms), and much, much older than the digital databases characteristic of the information age. In evolutionary terms, narrative co-developed with language, which in turn co-developed with human intelligence (see Deacon and Ambrose). Narrative, language, and the human brain are co-adapted to one another. The requirements for the spread of postindustrial knowledge that Alan Liu identifies—transformability, autonomous mobility, and automation—point to the emergence of machine intelligence and its growing importance in postindustrial knowledge work. It is not human cognition as such that requires these attributes but rather machines that communicate with other machines (as well as humans). In contrast to databases, which are well adapted to digital media, it is notoriously difficult to program intelligent machines to produce narratives, and those that are created circulate more because they are unintentionally funny than because they are compelling stories (see Wardrip-Fruin for examples). To that extent, narrative remains a uniquely human capacity.

In the twin perils of the Ludovician shark and Mycroft Ward, we may perhaps read the contemporary dilemma that people in developed countries face nowadays. In evolutionary terms, the shark is an ancient life-form, virtually unchanged during the millennia in which primates were evolving into homo sapiens. The Ward-thing is a twentieth and twenty-first-century phenomenon, entirely dependent on intelligent machines for its existence. Walking around with Pleistocene brains but increasingly immersed in intelligent environments in which most of the traffic goes between machines rather than between machines and humans, contemporary subjects are caught between their biological inheritance and their technological hybridity. Science fiction provides many examples of how this conundrum might be negotiated, including Arthur C. Clarke’s far-reaching exploration of immortality in The City and the Stars (1956), Vernon Vinge’s near-future technological hybridity in Rainbows End (2006), Laura J. Mixon’s vision of radical prostheses in Proxies (1998), and Greg Egan’s complex representation of a computational future in Permutation City (1993). What slipstream novels such as The Raw Shark Texts contribute to these explorations is to imagine a (post)human future in which writing, language, books, and narratives remain crucially important. With the passing of The Age of Print, books and other written documents are relieved of the burden of being the default medium of communication for twentieth and twenty-first-century societies. Now they can kick up their heels and rejoice in what they and they alone among the panoply of contemporary media do uniquely well: tell stories in which writing is not just the medium of communication but the material basis for a future in which humans, as ancient as their biology and as contemporary as their technology, can find a home.

NOTES

1. See my Writing Machines for an elaboration of this point. For a further discussion of the narrative-database distinction, see my “Narrative and Database.”

2. “Mycroft Ward,” as Pressman notes, is a near-homophone for “Microsoft Word”; like the ubiquitous software, Ward threatens to take over the planet. Mycroft is also the name of Sherlock Holmes’ elder brother, described by Arthur Conan Doyle as serving the British government as a kind of human computer: “The conclusions of every department are passed to him, and he is the central exchange, the clearinghouse, which makes out the balance. All other men are specialists, but his specialism is omniscience” (766). This, combined with his distaste for putting in physical effort to verify his solutions, makes him a suitable namesake. The reference is reinforced when Clio tells the First Eric that when she was hospitalized for cancer, she read Conan Doyle stories until she was sick of them (Hall 122).

3. The name Ward, and the reference to him as a “thing,” suggest a conflation of two H.P. Lovecraft stories of body-snatching and mind-transfer, The Case of Charles Dexter Ward (1941) and “The Thing on the Doorstep” (1937). Certainly, there is a Lovecraftian dimension to the fusion of technoscience and the occult in Ward’s scheme.

4. We are told that Mycroft Ward wants to take over the Second Eric because it knows that the Ludovician is hunting him and it needs the Ludovician in order to expand its standardizing procedure without limit (282-83). Although we are not told why the Ludovician would enable this expansion, it seems reasonable to conclude that the personalities of the node bodies put up some resistance to being taken over, and overcoming this resistance acts as a constraint limiting the number of node bodies to about a thousand. Apparently the idea is that the Ludovician will be used to evacuate the subjectivities that Ward wants to appropriate, annihilating their resistance and enabling Ward’s expansion into the millions or billions.

5. Hall follows the convention of omitting periods after Mr, Dr, etc.

6. For a mapping of these locations, see Hui (125).WORKS CITED

Ambrose, Stanley H. “Paleolithic Technology and Human Evolution.” Science 291.5509 (2 March 2001): 1748-53.

Deacon, Terrence W. The Symbolic Species: The Co-Evolution of Language and the Brain. New York: Norton, 1997.

Doyle, Arthur Conan. “The Adventure of The Bruce-Partington Plans.” 1912. The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes. Hertfordshire, UK: Wordsworth Editions, 1993. 765-82.

Genette, Gérard. Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method. 1972. Trans. Jane E. Lewin. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1983.

Hall, Steven. The Raw Shark Texts. Edinburgh: Canongate, 2007.

─────. The Raw Shark Texts. Toronto: HarperPerennial Canada, 2008.

Hayles, N. Katherine. “Narrative and Database: Natural Symbionts.” PMLA 122.5 (Oct. 2007): 1603-1608.

─────. Writing Machines. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2002.

Hui, Barbara Lok-Yin. Narrative Networks: Mapping Literature at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century. PhD Dissertation. University of California, Los Angeles. 2010.

Lacan, Jacques. “The Instance of the Letter in the Unconscious.” 1966. Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English. Trans. Bruce Fink, in collaboration with Héloïse Fink and Russell Grigg. New York: Norton, 2006. 412-43.

Lefebvre, Henri. The Production of Space. 1974. Trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith. London: Blackwell, 1991.

Liu, Alan. Local Transcendence: Essays on Postmodern Historicism and the Database. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2008.

Mangen, Anne. The Impact of Digital Technology on Immersive Fiction Reading: A Cognitive-Phenomenological Study. Saarbrücken, Germany: VDM, 2009.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2001.

Pressman, Jessica. “The Aesthetic of Bookishness in Twenty-First Century Literature.” Michigan Quarterly Review 48.4 (Fall 2009): 465-82.

Pynchon, Thomas. Gravity’s Rainbow. New York: Viking, 1973.

Ricoeur, Paul. Time and Narrative, Volume 1. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1990.

Sterling, Bruce. “Slipstream.” SF Eye #5. 1989. Online. 22 Nov. 2010.

Universes of Max Tegmark, The. Website of Max Tegmark, Professor of Physics, MIT. Online. 15 Dec. 2010.

Wardrip-Fruin, Noah. “Surface, Data, Interaction and Expressive Processing.” A Companion to Digital Literary Studies. Ed. Susan Schreibman and Ray Siemans. Oxford: Blackwell, 2008. 163-82.

Back to Home