#73 = Volume 24, Part 3 =

November 1997

|

|

|

I.F. Clarke

Future-War Fiction:

The First Main Phase,

1871-1900

Editors' Note: This article received the

Pioneer Award from the Science Fiction Research

Association for the best critical essay on science

fiction published in 1997.

|

|

Only the most perverse would

reject the proposition that an evolutionary process of

challenge and response has controlled and directed the tale

of the war-to-come ever since that far-off day in 1644, when

the citizens of London first had sight of a six-page fantasy

about the Civil War then raging in England. This was

Aulicus his Dream of

the Kings Sudden Comming to London--a primitive thing, filled with

passion recollected in tumultuous disquiet. The author was

Francis Cheynell, who was notorious enough to secure a minor

place in the Dictionary of National

Biography, where he

appears as a Puritan fanatic well known for his detestation

of Charles I and all he represented.

Cheynell is the first

dreamer in futuristic fiction. He relates how he fell asleep

afflicted by thoughts of the Civil War, and in a protracted

nightmare he has a fearful vision of King Charles triumphant

over Cromwell and the forces of Parliament. That political

fantasy had bite in the May of 1644, when it was still

thought possible that the king could prove the victor in the

Civil War. With that in mind Cheynell did what so many would

go on doing long after him. Within the limitations of six

pages he told his tale of the disaster-to-come as

dramatically as he could, so that readers would have no

doubt that the meaning of his message was: ACT NOW BEFORE IT

IS TOO LATE.

Few followed where Cheynell

had boldly gone. For two and a quarter centuries after the

appearance of Aulicus

his Dream, the

history of future-war fiction was a series of occasional and

usually most unremarkable stories--so few in number that a

modest brief-case could contain them all.1 And then quite suddenly the great

powers of the press, politics, and population came together

in 1871, when Chesney's Battle of Dorking touched off the chain reaction of

future-war stories which continued without cessation until

the outbreak of the First World War. From 1871 onwards not a

year went by without the appearance of a tale of the

war-to-come in Britain, France, or Germany. At times of

major anxiety--the Channel Tunnel panic in 1882, the Agadir

Crisis of 1911, for instance--they appeared by the dozen;

and the probable total for the period from 1871 to 1914 is

not less than some four hundred stories in English, French,

or German. Those languages point to a massive European

interest in The Next

Great War, der nächste Krieg, La Guerre de

demain, as they

called it in the cheerful language of anticipation. Their

tales of the war-to-come were joined together in an unholy

marriage of conflicting interests. They owed the origin, the

circumstances and the consequences of their projected

conflicts to the Other. Locked in a necessary and unloving

embrace with tomorrow's enemy, they found complete

justification for their narratives in the often repeated

claim that their future war would be the next phase in the

history of their nation.

As these tales of the

war-to-come grew in numbers from the 1880s onwards, the

range of their preoccupations expanded so that by the end of

the 19th century a paradigm of military and political

posibilities had come into existence both in Europe and in

the United States. At the far-out paranoid end there were

the total fantasies of the Yellow Peril, of Demon Scientists

and Anarchists, all armed with the most fearful weapons

conceivable and all hell-bent on taking over the world.

These all require, and may yet obtain, their own separate

assessments; but for the present it is enough to say that

the Yellow Peril was one theme the Europeans had in common

with the United States. As Bruce Franklin has shown in

War

Stars (pp. 33-45),

the American versions began with Pierton Dooner's

Last Days of the

Republic in 1880,

and within two decades they had become a flood. During that

time the Europeans did almost as well: Jules Lermina in

La Bataille de

Strasbourg (1895)

described how a scientist blows up Mont Blanc and destroys

the invading Asiatics; the British writer, M.P. Shiel, dealt

with the Chinese attempt to conquer the world in

The Yellow

Danger (1898); and

the Asians were still on the move in 1908 in Bansai!, a German account of a Japanese

attack on the United States by Parabellum (Ferdinand

Heinrich Grautoff).

These were future-war themes

taken to the limit. They had no immediate and substantial

links with the contemporary world situation, as Capitaine

Danrit made clear when he dedicated his three-volume tale of

L'Invasion

noire

(The Black

Invasion, 1895-6) to

Jules Verne. He wrote that his account of a future invasion

of Europe--by hordes of fanatic African Muslims led by a

sultan of genius-- ``...depended on a very questionable

proposition, since the reverse is happening in our age. The

European powers are carving up the Dark Continent as they

like, and they are distributing the primitive populations

amongst themselves as if they were cheap livestock'' (2).

That uneasiness with European colonialism was the trigger

for an imaginary eruption of overwhelming forces--Chinese,

Japanese, Africans--who play their own imperial power-games

with the Western world. The contemporary versions of the

``Bad American Dream,'' for example, clearly derived from

subliminal anxieties about the ``enemy within'' in King

Wallace's The Next

War: A Prediction

(1892), and from American anxieties about the new Japan in

J.H. Palmer's The

Invasion of New York; Or, How Hawaii was

Annexed (1897). For

those who had the courage of their racial prejudices,

however, there was a final solution for the nightmare from

the East--wipe out the inferior races.

Two stories are prime

contenders for the title of the Best in Genocide Fiction:

the first, and likely winner on length, is the chapter on

``The Fate of the Inferior Races'' in Three Hundred Years

Hence (1881) by the

one-time Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, William

Delisle Hay; the second is the short story, ``The

Unparalleled Invasion,'' a by-product of Jack London's work

as a war correspondent during the Russo-Japanese War. The

British author looked forward to the perfect world of the

Victorian dream--advanced technologies, universal peace and

plenty, the white races united within the Oecumenic

Parliament of the States of Humanity. Throughout the Century

of Peace, Hay wrote, ``men's minds had become opened to the

truth, had become sensible of the diversity of species, had

become conscious of Nature's law of development ...The stern

logic of facts proclaimed the Negro and the Chinaman below

the level of the Caucasian, and incapacitated from advance

towards his intellectual standard'' (235). Nature's law

required that the Caucasians should inherit the world. Vast

air fleets sweep across China and discharge ``a rain of

awful death upon the `Flowery Land' below...

... a rain of

death to every breathing thing, a rain that exterminates the

hopeless race, whose long presumption it had been, that it

existed in passive prejudice to the advance of United

Man.

What need is there to say

more? You know the awful story, for awful it undoubtedly is,

that destruction of a thousand millions of beings who once

were held to be the equals of intellectual men. We look back

upon the Yellow Race with pitying contempt, for to us they

can but seem mere anthropoid animals, not to be regarded as

belonging to the race that is summed and glorified in United

Man. (248)

The American argument for

wiping out the Chinese did not cite ``Nature's law of

development.'' It was, in the words of Jack London, a matter

of simple prudence: ``There was no combating China's amazing

birth-rate. If her population was 1000 millions and was

increasing 20 millions a year, in twenty-five years it would

be 1500 millions--equal to the total population of the world

in 1904.''2 The final solution starts with the

United States in 1975, when President Moyer brings the major

White powers together for the destruction of all human

beings in China. On 1 May 1976 their planes begin dropping

``strange, harmless-looking missiles, tubes of fragile glass

that shattered into thousands of fragments on the streets

and housetops'' (269). It is the start of a planned

programme of bacteriological warfare. ``During all the

summer and fall of 1976, China was an inferno...

There was no

eluding the miscroscopic projectiles that sought out the

remotest hiding-places. The hundreds of millions of dead

remained unburied, and the germs multiplied; and, toward the

last, millions died daily of starvation. Besides starvation

weakened the victims and destroyed their natural defenses

against the plague. Cannibalism, murder and madness reigned.

And so China perished.3

These extreme fantasies

derived from the ceaseless dialogue between Western culture

and the immense, ever-growing powers which the new

industrial societies had generated since that day on Glasgow

Green in 1764 when James Watt got the idea for the separate

condenser. One hundred years later Jules Verne began his

most profitable career as the first great writer of science

fiction by demonstrating the most desirable applications of

the new technologies in the achievements of Nemo, Robur, and

the Baltimore Gun Club. And then in Les 500 Millions de la

Bégum

(The Begum's

Fortune, 1879) he

looked at the morality of intentions in the use of

scientific knowledge. Franceville is the ideal city,

dedicated to peace, the happiness of its citizens, and the

good of humankind; Stahlstadt is the dark opposite, the home

of Dr Schulze and his super-gun--totalitarian, regimented,

bent on the conquest of the world. The unwritten conclusion

was that, given sufficient power, anyone--any nation, any

group, any race--could take control of planet Earth. No one

put this better than H.G. Wells in the most telling and most

effective of all future-war stories, The War of the Worlds

(1898). In that

classic tale Wells began with the notion of superior force,

as it had been suffered by the Tasmanians who ``...in spite

of their human likeness, were entirely swept out of

existence in a war of extermination waged by European

immigrants in the space of fifty years.'' When the Martian

cylinders land on the common between Horsell and Woking, the

rifles and artillery of the British prove as useless as the

wooden clubs of the Tasmanians. The super-weapons of the

Martians--all the fire-power and mobility any general could

desire--were warning images of what science might yet do for

the military.

As contemporary weaponry

continued to advance, Wells pursued the theme of

ever-accelerating power and came down to earth from

planetary space. First, he looked at what technology could

do on the battle-field in ``The Land Ironclads'' (1903).

Then, he looked at total warfare in a terrestrial setting in

The War in the

Air (1908)--the

destruction of New York and the collapse of all human

society in that near-future time when ``the great nations

and empires have become but names in the mouths of men.''

And then he produced the most perceptive anticipation in

future-fiction with his account of atomic warfare in

The World Set

Free (1914). He

confronted the ultimate weapon and thought that the immense

destructiveness of the atomic bomb (he gave the term to the

world) would lead to world peace and to ``the blazing

sunshine of a reforming world.''

This discussion of military

power provided abundant material for a parallel sequence of

more conventional tales about ``What It Will be Like in The

Sea Warfare of Tomorrow.'' These were a straightforward form

of future-war fiction--all the fighting without the

politics--for the narratives concentrated almost entirely on

the operations of naval vessels. They were written as

answers to serious questions prompted by the coming of the

ironclad warship, by the introduction of the ram, and by the

development of the destroyer and the submarine. And here

again national interests decided the distribution of these

stories. British writers dominated the field for the good

reason that the Royal Navy was the first line of national

defence for the United Kingdom.4 German writers were conspicuous by

their absence. They had nothing to write about, since the

new Reich did not start on a naval building programme until

the first Navy Law of 1898. The French were more interested

in, and wrote more about, their army; and across the

Atlantic, as Bruce Franklin has demonstrated in

War

Stars (23-33),

American propagandists were turning out preparedness tracts

to present the case for the great navy that the United

States did not have in the 1880s.

One of the best examples of

this anticipatory fiction came from the British Member of

Parliament, Hugh Arnold-Forster, later Secretary of the

Admiralty. He wrote his tale of a ramming action,

In a Conning Tower: A

Story of Modern Ironclad Warfare (1888), in order to give his readers

``a faithful idea of the possible course of an action

between two modern ironclads availing themselves of all the

weapons of offence and defence which an armoured ship at the

present day possesses''(ii). It proved most popular: after

appearing in Murray's

Magazine (July

1888), the story went through eight pamphlet editions, and

there were translations into Dutch, French, Italian, and

Swedish. There was a comparable interest in Der grosse Seekrieg im Jahre

1888

(The Great Naval War

of 1888), written by

Spiridion Gop evi , an officer in the Austrian Navy. His

elaborate account of naval tactics in a war between the

British and French first appeared in the highly professional

Internationale Revue

über die Gesamten Armeen und Flotten in 1886, and in the following year

the story went into an immediate English translation as

The Conquest of

Britain in 1888.

One unusual feature of these

naval anticipations was the good temper and the remarkable

courtesy of the authors--a welcome change from the

propaganda and invective of tales like Samuel Barton's

The Battle of the

Swash and the Capture of Canada (1888), George La Faure's

Mort aux

Anglais!

(Death to the

English!, 1892), or

Karl Eisenhart's Die

Abrechnung mit England (The Reckoning with

England, 1900). For

instance, the British naval historian, William Laird Clowes,

assured his readers that in writing his tale of

The Captain of the

``Mary Rose'' (1892)

he had ``been animated by no unfriendly and by no unfair

feelings towards France.'' Again, F.T. Jane, the journalist

and the founder of the influential Jane's Fighting Ships, began his account of

Blake of the

``Rattlesnake'' (1895) with a long preamble about

``future war yarns.'' They could not be a danger to peace

between nations for the simple reason that ``Foreign nations

are frequently turning out similar stories; yet I have never

heard of any of us bearing them ill-will for it.'' In like

manner the anonymous naval lieutenant who wrote

La Guerre avec

l'Angleterre

(The War with

England, 1900) began

by saying that his subject was the war at sea, and that

meant:

For France there

can only be one naval war--against the British. It does not

follow from this that France should fight the British, nor

that France should have a greater interest in making war

than in maintaining the peace. It is even less permissible

to think that France should wish for a war with the British.

(v)

The evident popularity of

these various tales of the war-to-come marks a sudden and

extensive change in long-established modes of communication.

Almost overnight fiction had replaced the tract and the

pamphlet as the most efficient means of airing a nation's

business in public. For centuries ``the address to the

nation'' had done good service in warning of the

dangers-to-come--from the first signals of alarm at the

coming of the Invincible Armada in 1588 to the outpouring of

pamphlets that accompanied, and often profoundly influenced,

the course of events in the United States in 1776, in France

in 1789, and in Great Britain during the time when the

Armée de l'Angleterre was waiting in Boulogne to

start on the invasion of England.

Although the undisputed

effectiveness of Chesney's Battle of Dorking was a most potent force in

encouraging this shift into fiction, the prime movers in the

great change were a combination of social and literary

factors. First, there was the matter of demand and supply:

the constant growth of populations and the parallel rise in

the level of literacy provided more and more readers for the

increasing numbers of newspapers, magazines for all

interests, and books of every kind. Second, a new and most

influential conclave of historians demonstrated, often with

great eloquence, how their nations had secured their place

in the nineteenth-century world. So, an exclusive sense of

nationhood fed on and grew out of the new histories, which

were the life-work of eminent writers like Guizot, Thierry,

Michelet, Francis Parker, Macaulay, Carlyle, Buckle, von

Ranke, Treitschke. In keeping with the general belief in

``progress,'' they explained the evolution of their nations

as the work of exceptional individuals and the result of

communal movements, of struggles with other nations, and of

decisive victories at Austerlitz, Saratoga, and

Waterloo.

The new, centralised systems

of education passed on their simplified versions of

one-history-for-one-people to the state schools, so that by

the 1890s the young in all the major technological nations

had received an appropriate grounding in the received

history of their country. Again, and for the first time in

human history, the young could see the evolution of the

nation state in the maps that showed the unification of the

German states, or the advance out of the thirteen colonies

westward towards the Pacific, or the lost provinces of

Alsace-Lorraine, or the many additions to the British

Empire.

In the parallel universe of

the new historical fiction, the heroic individual had his

appointed role in the male worlds of Walter Scott, Victor

Hugo, Fenimore Cooper, Alessandro Manzoni, and many others.

In their various ways they sought to reveal the intimate

links between character and action, between the person and

the nation. And so, in January 1871, when Chesney was

considering what would serve him best as a model for the

tale about a German invasion he had contracted to write, he

thought immediately of fiction in the style of

Erckmann-Chatrian. Those two most popular writers had set

their tales about the ``Conscript'' in the well-established

circumstances of the Napoleonic Wars. Their handling of

their stories was an ideal example for a British colonel who

wished to show that the projected events in his history of

the coming invasion would follow from the faults and

failings of the nation in 1871. These errors of the past--so

evident, so avoidable, so serious--gained a powerful

psychological spin from a future history that could handle

disaster or victory with equal facility. The time-frame

recorded events as a chapter, often the last chapter, in the

national history: victory happily and gloriously confirmed

the national destiny; and defeat allowed for telling

contrasts between the final disaster and the better days

gone beyond recall.

All these tales of the

war-to-come advanced along the contour lines of contemporary

expectations. The majority--some two-thirds of them--kept

closely to the political, military or naval facts; and,

whenever their authors had a warning to deliver, they waved

the big stick of fiction at their readers. Most of their

tales were admonitory essays in preparedness--arguments for

a bigger army, or for more ships. Since most of these

authors were responding to some danger or menace represented

by the enemy of the day, they were usually careful to

present their accounts of the war-to-come as the next stage

in the nation's history. Chesney did this very well in the

opening sentences of his Battle of Dorking. His many imitators noted, and often

adopted, the deft way in which he established the time and

scale of the future disaster, as he began his ominous

woe-crying in his first lines:

You ask me to

tell you, my grandchildren, something about my own share in

the great events that happened fifty years ago. 'Tis sad

work turning back to that bitter page in our history, but

you may perhaps take profit in your new homes from the

lesson it teaches. For us in England it came too late. And

yet we had plenty of warnings, if we had only made use of

them. The danger did not come on us suddenly unawares. It

burst on us suddenly, 'tis true, but its coming was

foreshadowed plainly enough to open our eyes, if we had not

been wilfully blind.

Transfer that threat from

the external enemy to an American setting, and

``Stochastic'' (Hugh Grattan Donnelly) responds with a

Chesney-style lamen-tation to introduce an American argument

for strengthening the national defences. He begins his

history of The

Stricken Nation

(1890) by recalling the good years before the British fleet

reduced New York to rubble and caused immense damage to the

Eastern sea ports:

The pages of

universal history may be scanned in vain for a record of

disasters, swifter in their coming, more destructive in

their scope, or more far-reaching in their consequences,

than those which befell the United States of America in the

last decade. Standing on the threshold of the twentieth

century, and looking backward over the years that have

passed since the United States first began to realize the

tremendous possibilities of the impending crisis, we are

amazed at the folly and blindness which precipitated the

struggle, while bewildered and appalled by its effects on

the destinies of mankind.

In 1891 we behold a nation!

A Republic of sixty-two million ... an intelligent, refined,

progressive people; peace and plenty within their borders

from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and from the shores of the

Great Lakes to the Gulf. In 1892, we see the shattered

remnants of the once great Republic. We read with

tear-dimmed eyes of its tens of thousands of heroes fallen

in defence of its flag, of its thousands of millions of

treasure wasted in tardy defence, or paid in tribute to the

invader.

It was standard practice to

start from established positions in the political geography

of Europe or of the United States. The French, for example,

saw a war with Germany and the recovery of Alsace-Lorraine

as no more than patriotic duty. That agreeable prospect

provided cause and consequence for a succession of

anticipations that began in the year of defeat with: Edouard

Dangin, La Bataille

de Berlin en 1875

(The Battle of Berlin

in 1875, 1871). That

theme reappeared five years later in Anonymous,

France et l'Allemagne

au printemps prochain (France and Germany Next

Spring, 1876); and

again in 1877 in Général Mèche,

La Guerre

franco-allemande de 1878 (The Franco-German War of

1878). These were

the first in an ever-growing flood of these guerres imaginaires that reached the highest-level mark

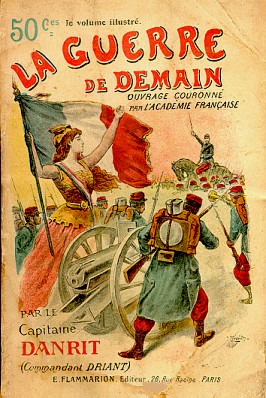

in the many publications of Capitaine Danrit (Commandant

Emile Augustin Cyprien Driant, 1855-1916). He belonged to

the new fraternity of senior officers--patriot writers to

the public--who chose to make their appeals to the masses

through the medium of fiction; for they knew from the

success of Chesney's Battle of Dorking that a tale of the war-to-come,

fought against the expected enemy, was the most effective

means of putting the case to their citizen paymasters for

more funds for more troops and for more warships.

Commandant Driant was an

eminent person, like so many of the authors who wrote

future-war stories before the journalists of the new mass

newspapers took over from them about the turn of the

century. He was commissioned into the infantry and after

eleven years of service with the colours he was appointed

adjutant to General Boulanger at the Ministry of War in

1888. In that year the general's political activities led to

the removal of his name from the army list and in that same

year Driant married the general's youngest daughter and

began work on his first guerre imaginaire. The distinguished record continues:

instructor at St. Cyr; battalion commander by 1898; resigns

commission in 1906 and goes into politics as the deputy for

Nancy; dies a hero's death on the Verdun front in

1916.

The biography reveals an

ardent patriotism and a determination to prepare the French

for the war that they would one day have to fight with

Germany. He made this very clear in his dedication of

La Guerre en rase

campagne

(War in Open

Country, 1888) to

his old regiment, 4e Régiment de Zouaves:

With you I would

have liked to depart for the Great War, which we are all

expecting and which is so long in coming. Under your flag I

still hope to see it, if there is a god of battle and he can

hear me. To while away the waiting I have dreamed of this

war, this holy war in which we shall be victorious; and this

is the book of my dream which I dedicate to you.'

Driant always gave his

readers what they wanted: heroic episodes, great victories

over the Germans, and in the 1192 pages of his

Guerre fatale:

France-Angleterre

(The Fatal War:

France-England,

1902) he had ample space in which to relate the total defeat

of the British. Driant has a world record as the man who

turned out more future-war stories (some twelve in all) than

any other writer before 1914. In 1888 he opened the war

against Germany in La

Guerre de demain

(The War of

Tomorrow) with the

first of three full-length stories which told the tale of:

La Guerre en

forteresse

(Fortress

Warfare),

La Guerre en rase

campagne

(War in Open

Country), and

La Guerre en ballon

(Balloon Warfare). As the scene of battle shifts from

forts to open country and to the skies, Driant works to link

the history of France with his version of la guerre de l'avenir. The action opens in La Guerre en

fortresse, as

reports come in of a sudden German attack. Danrit goes into

stereotype mode: the good French face the dastardly Teutons

who have not declared war. The troops stand to in their

positions, and at dawn their captain addresses them ``in a

serious voice ...

`Mes enfants,

the great day of battle has arrived, the one I have so often

spoken about in our theoretical lectures. The Germans are on

the move, advancing towards our line of forts. They are

attacking us without any declaration of war, and without any

provocation from our side, like one nation that wants to

annihilate another. We are fighting for our lives, for our

survival, for our homes. If we are defeated, we shall be

removed from the map of Europe; we shall cease to be a

military power.If we are victorious, that will be a very

different matter. Here, in this small corner of France we

shall soon be cut off from the rest of the world. We are

going to face determined attacks; we shall face danger every

second. Steel your hearts for this task! There cannot be any

doubt that I would have preferred to march with you in open

country, behind the regimental flag, but fate has decided

otherwise. We have to guard one of the gateways of France.

To let the enemy take it by storm would be most shameful; to

surrender it would be a crime. I have been a prisoner in

Germany; and in Cologne I went through all the humiliation

of defeat after the great battles we fought over

there.'

And his voice trembled with

emotion as his finger pointed in the direction of

Metz.

`I am too old to go through

that again,' he said in a solemnn tone that moved us

profoundly. `Swear all of you that you are ready to die with

me in defending the fort of Liouville which France has

entrusted to us.'5

By 1913 Driant had published

so much fiction, and his stories were so long that half a

century later Pierre Versins felt called on to protest in

the name of sanity. The hundred pages of Chesney's

Battle of

Dorking, said Pierre

Versins in his admirable Encyclopédie, were far more important and

revealing ``than the thousands of white pages soiled day

after day by a national hero of France (they dedicated a

postage stamp to him in 1956). Thousands? Judge for

yourself!

|

La Guerre de

demain

|

2827pp |

|

L'Invasion noire

|

1279pp |

|

La Guerre

fatale

|

1192pp |

|

L'Invasion

jaune

|

1000pp |

|

L'Aviateur du

Pacifique |

512pp |

|

L'Alerte |

454pp |

|

La Guerre

souterraine

|

332pp |

|

TOTAL |

7616pp

6 |

A comparable association

between the British public and the military can be examined

in the ways General Sir William Francis Butler (1838-1910)

and his wife exploited the general interest in warfare. He

had distinguished himself in various colonial

operations--the Ashanti campaign, the Zulu War,

Tel-el-Kebir--and he went on from one senior post to

another, and ended his career as a lieutenant-general in

1900. In between campaigns he found time to make his

contribution to the growing literature of future warfare

with The Invasion of

England (1882), a

variant on an already well-established theme. His wife,

however, was far more famous. The battle-paintings of the

celebrated Lady Butler were reported at length in the Press;

they attracted huge numbers of viewers whenever they were

shown at the Royal Academy; and the editors of the principal

illustrated magazines spent thousands of pounds to secure

rights of reproduction. When her paintings went on tour, it

was reported that viewers queued for hours. The showing of

the famous painting of Balaclava, for instance, attracted some 50,000

at the Fine Art Society in 1876 and when it arrived in

Liverpool, more than 100,000 had paid to see the

picture.

The general had made the

connection between military preparedness and the future of

the nation in his one venture into the fiction of

future-warfare; and his wife gained an international

reputation for paintings that showed the masses the

life-and-death connection between the history of the nation

and the courage of the ordinary soldier. In her most admired

works--The Roll

Call,

The 28th Regiment at

Quatre Bras,

Scotland for

Ever!--she revealed

how much she had profited from the style of the French

genre

militaire,

especially from the realism and accuracy of the most famous

of the French military painters, Jean Louis Meissonier. He

thought highly of her battle scenes, and he has been quoted

as saying of Lady Butler: ``L'Angleterre n'a guère

qu'un peintre militaire, c'est une femme.''7

The French had created their

own heroic iconography out of their exceptional military

history. A succession of gifted painters--Horace Vernet,

Adolphe Yvon, Alphonse de Neuville, Edouard Detaille, and

the incomparable Jean Louis Meissonier--revealed the supreme

moments of victory and defeat. To look backward was to see

the glorious past, battle by battle, and one great warrior

after another, as they appear to this day in the ``Salle des

Batailles'' at Versailles. To look forward to the war of the

future, however, required gifts of imagination that were

peculiar to only one man. Albert Robida (1848-1926) was the

Jules Verne of the sketch pad and the magazine drawing. The

two men quarried from the new technologies for their vision

of things-tocome; and both had their base in the new

magazines--for Verne the Magasin d'éducation et de

récreation;

for Robida his own La

Caricature. Where

Verne was all high seriousness in his stories, Robida was

relaxed and amused at the images that came to him out of the

future. He looked into the twentieth century in his

Le Vingtième

Siècle

(The Twentieth

Century, 1883) and

found a world where the droll, whimsical images confirmed

the fact of progress and universal prosperity: air taxis,

aeronefs-omnibus, transatlantic balloons, aerial hotels,

apartment blocks made from compressed paper, television for

all, synthetic foods, submarine cities, underwater sports,

and a women-only stock exchange.

Robida was equally at his

ease with the possibilities of future warfare. His first

anticipation of la

guerre qui vient

appeared in La

Caricature. This was

the famous account of La Guerre au vingtième

siècle

(War in the Twentieth

Century, #200, 27

October 1883), and then a revised version came out in a

magnificent 48-page album in 1887. It was a remarkable

moment in the history of publishing. An amiable French

civilian with a wry sense of humour had produced the first

images of what the sciences could do for the military. His

alphabet of aggression revealed the extraordinary shape of

things to come: armoured fighting vehicles, bacteriological

weaponry, bombers, chemical battalions, female combat

troops, fighter planes, flame-throwers, poison gas provided

by the Medical Assault Corps, psychological warfare experts,

underwater troops. Although his drawings were well ahead of

their time, Robida was a true man of his times in the

nonchalance he showed in contemplating the most lethal

weapons then conceivable. We know now what was then hidden.

The planners and the prophets had drawn the wrong

conclusions from the unprecedented advances of the age. A

sturdy confidence in the continued progress of humankind

encouraged the belief that the new weapons would lead to

shorter, even better wars. In 1901, for example, at the end

of a chapter on ``Changes in Military Science,'' a senior

instructor at West Point set down the then current American

military doctrine that ``wars between civilized nations,

when carried on by the regularly organized forces, will be

short.'' He reasoned that ``the great and increasing

complexity of modern life, involving international contacts

at an ever-increasing number of points, will combine with

the military conditions herein outlined to reduce the

duration of war to the utmost.''8

This view of coming things

is apparent in Robida's draughtmanship. His images are

brilliant, now slightly archaic anticipations of what the

military would achieve in the twentieth century.

Unfortunately Robida's writing is not the equal of his

drawing. His narrative finds its own place in the

never-never void of a fantastic future-history, as if Robida

could never bring himself to make the obvious conclusions

from the lethal weaponry he had drawn. The story opens, for

instance, on the droll note that Robida reserves for the

more destructive events in his narrative:

The first half

of the year 1945 had been particularly peaceful. Apart from

the usual goings-on--that is, apart from a small three-month

civil war in the Danubian Empire, apart from an American

offensive against our coast which was repulsed by our

submarine fleet, and apart from a Chinese expedition which

was smashed to pieces on the rocks of Corsica--life in

Europe continued in total calm.9

Again, Robida uses the

desperate and often hilarious adventures of his intrepid

hero, Fabius Molinas from Toulouse, as his best means of

keeping the reader amused with the unfolding jollity of

total warfare. The narrative moves with lightning speed, as

Molinas goes through a series of rapid promotions for the

sake of the images--air gunner to pilot officer to

second-lieutenant in the mobile artillery to commandant of

``the Potassium

Cyanide, a submarine

torpedo vessel of entirely new construction'' (105). As

Molinas survives disasters far beyond the call of duty, the

swift and somewhat flippant style keeps the narrative going

at such a speed that the reader has little time to ponder

the consequences of the more striking incidents. On

occasions Robida seems to point towards a far from

comfortable conclusion. There is, for example, the air

attack on a town:

There was a loud

cry, and a puff of smoke. Three more bombs followed; and

then there was total silence. The camp fires had been

extinguished, and a pall of death covered all, even the

wretched inhabitants who had stayed on in the town. They

were all instantly suffocated in their homes. These things

are the accidents of war to which the recent advances of

science have accustomed all of us.10

Robida was the Lone Ranger

in the French guerres

imaginaires: one of

the very few (like A.A. Milne and P.G. Wodehouse) who found

it possible to be funny about ``the next great war.'' He

rescued his comic tale from the Bastille of real events,

because he was able to ignore contemporary politics, unlike

the hundreds of earnest writers--British, French, and

German--for whom the tale of the European war-to-come was a

desirable extension of national policy by means of fiction.

For that reason these tales often sold well, and went on

selling in sudden bursts of popularity whenever some

perceived danger attracted the attention of a nation. In

1882, for instance, the proposals for the construction of a

Channel Tunnel set the alarm bells ringing in the United

Kingdom; and, as the arguments against so imprudent, so

perilous a connection with the Continent went the rounds of

the Press, anxious patriots took to writing fearful tales

that promised the worst in their titles: The Seizure of the Channel

Tunnel,

The Surprise of the

Channel Tunnel,

How John Bull Lost

London,

The Siege of

London,

The Story of the

Channel Tunnel,

The Battle of

Boulogne. The best

of these was the work of Howard Francis Lester, a barrister

and an eminent person in the British legal system. In

The Taking of

Dover (1888) he told

a tale of French treachery--of French assault troops hidden

in Dover, waiting for the day when they could emerge to

seize the town and begin the invasion of England. The tale,

slotted into an appropriate place in French history, is told

after the conquest by the commander of the assault troops

who shakes his head with great effect at his recollections

of British folly and unpreparedness. It seemed only

yesterday they were plotting the seizure of Dover, and now

he could not ``but pity the nation; but their humiliation,

as it was occasioned by sheer recklessness, by avarice for

the gains of trade, and by blind stupidity, appears to my

judgment to have been fully deserved'' (11).

Link to: Selected

illustrations from Robida's La Guerre au Vingtième

Siècle

The topicality of tomorrow's

peril guaranteed that most of these stories would have their

brief day of popularity before they vanished into the hands

of the rare-book dealers. At their most notorious best,

however, they can still bring home the seriousness of

politics at the times of major crises; and they reveal how

easy it was for the citizens of the pre-1914 world to

believe that a future European war would be a short

affair--without immense casualty lists, fought with

conventional weapons, and conducted in a reasonably humane

way. They were writing about, and preparing for, the wrong

war. One of the ablest historians of the First World War has

pointed out that

The nations

entered upon the conflict with the conventional outlook and

system of the eighteenth century merely modified by the

events of the nineteenth century. Politically, they

conceived it to be a struggle between rival coalitions based

on the traditional system of diplomatic alliances, and

militarily a contest between professional armies--swollen,

it is true, by the continental system of conscription, yet

essentially fought out by soldiers while the mass of the

people watched, from seats in the amphitheatre, the efforts

of their champions.11

A benign conspiracy had made

it impossible for all but the very few to see that the rapid

advances in weaponry would change the scale of warfare. For

example, the favourite dogma of technological and social

progress caused Charles Richet--the distinguished

bacteriologist and winner of the Nobel Prize for

medicine--to forecast a best of all possible future worlds

in his Dans cent

ans (In One Hundred Years, 1892). Eight years before the

Wright brothers began their flights at Kitty Hawk, Richet

was confident that the prospect of everlasting peace was

growing day by day, because modern armaments had brought the

nations up before the ultimate deterrent. Vast national

armies had replaced the small forces of earlier times; and

as for their weaponry,

Quick-firing

rifles, enormous guns, improved shells, smokeless and

noiseless gunpowder--these are so destructive that a great

battle (such as there never will be, we hope) could cause

the deaths of 300,000 men in a few hours. It is evident that

the nations, no matter how unconcerned they may be at times

when driven by a false pride, will draw back before this

terrible vision.

But things are changing for

the better. New means of warfare,probably more destructive

than ever, are on the drawing-board. By continually

improving our armaments, we will end by making war

impossible. Should flying machines ever be invented, they

will spread devastation everywhere. No town, no matter how

far it is from the frontier, will be able to defend

itself.12

Richet had no figures to

support his belief that the nations would ``draw back before

this terrible vision,'' whereas Ivan Bloch produced a

mountain of statistics in the six volumes and 3094 pages of

his lengthy treatise on The Future of War. For some nine years Bloch had

studied every war since 1870--everything from the numbers of

combatants, ammunition supply, rate of fire to casualty

lists--and he had come to the conclusion ``that war has

become impossible alike from a military, economic, and

political point of view.....

The very

development that has taken place in the mechanism of war has

rendered war an impracticable operation. The dimensions of

modern armaments and the organization of society have

rendered its prosecution an economic impossibility; and,

finally, that if any attempt were made to demonstrate the

inaccuracy of my assertions by putting the matter to a test

on a great scale, we should find the inevitable result in a

catastrophe which would destroy all existing political

organizations. Thus, the great war cannot be made, and any

attempt to make it would result in suicide.13

The general view was the

very opposite. What the majority expected can be examined in The Great War of

189- (1891), the

first-ever piece of future-war writing composed by a

consortium of military and naval experts. This was an action

replay of contemporary assumptions and expectations about

the most likely conduct of operations on land or at sea in a

future European war; and it did in its time what General Sir

John Hackett and associates set out to do in their Third World

War (1978). The

publication of the story in the then new illustrated

magazine, Black and White, is even more significant than its

contents. It was the first full-length illustrated study of

``the next great war''--the parts appeared weekly from 2

January to 21 May 1891. Moreover, the editor of Black and

White had

commissioned the story--as he told his readers in his

introduction to the first part--in order to give them ``a

full, vivid and interesting picture of the Great in War of

the future.''

That bid to increase the

print run of a new magazine marked the beginning of a new

trend in the Press. The war-to-come had moved out from its

original base in the middle-class journals and had become a

valued commodity for the mass-circulation magazines and

newspapers that began to appear in the 1890s. Thus, the

editorial hand can be seen at work in the presentation of

the story. One major innovation showed in the realism and

careful attention to detail in ``the scene of action'' style

of the narrative. This was most evident in the

up-to-the-minute accounts that told the tale in a sequence

of dated reports from the front, telegrams from

correspondents with the combatants, and editorial comments

in the manner of contemporary newspapers. Another innovation

in this search for the authentic appeared in the frequent

first-class action illustrations--the work of outstanding

contemporary war artists who sought to give the impression

of on-the-spot photography. Again, the members of the

writing team represented an array of the major talents. The

co-ordinator was the distinguished naval officer,

Rear-Admiral P. Colomb, known as ``Column and a Half'' from

his habit of writing long letters to the Times. He contributed the naval episodes,

and he edited the land warfare accounts from Charles Lowe, a

distinguished foreign correspondent of the Times, and Christie Murray who had been

the special correspondent of the Times during the Russo-Turkish War of

1877.

The great war of 189- begins

in the Balkans, in keeping with general expectations; and

the immediate cause proved unusually prescient--the

attempted assassination of Prince Ferdinand of Bulgaria. The

ultimate cause--a preview of 1914--is the chain-effect of

the Triple Alliance between Germany, Austria-Hungary, and

Italy. The action begins with the Serbian attack on

Bulgaria. The Austrians occupy Belgrade as a precautionary

move; and in response the Russians occupy the principal

Bulgarian ports on the Black Sea. Germany mobilizes in

support of Austria-Hungary; the French rally to Russia and

declare war on Germany. The United Kingdom begins by keeping

to the traditional policy of ``glorious isolation,'' but is

eventually drawn into the conflict against the French and

the Russians. Well-known contemporary

personalities--political, military, naval--play their parts

in this drama of the expected. There are various major

engagements on land and sea, most of them one-day affairs,

in a war of rapid movement with infantry advancing at the

double and grand cavalry charges. There are no long casualty

lists; all combatants behave like gentlemen; and the war is

over by Christmas.

From 1890 onwards the tale

of the war-to-come adapted to the new circumstances of an

ever-growing demand from the burgeoning popular press.

Editors began to commission tales of ``the next great war.''

One of the first into the new business was that astute

entrepreneur, Alfred Harmsworth. He began a most profitable

association with the sensational writer, William Le Queux,

when he commissioned a future-war story for his new tabloid, Answers. This was

The Poisoned Bullet, a tale of a Franco-Russian

invasion, which ran for six months and ended on 2 June 1894.

The yarn went on to even greater success. When it was later

published as a book with the title of The Great War in England in

1897 (1894), it ran

through five editions in a month, and attracted attention in

France, Italy, and Germany. Twelve years later Harmsworth

(by then elevated to Viscount Northcliffe) made the

newspaper coup of the pre-1914 period. In 1906 he

commissioned Le Queux to write a serial, The Invasion of 1910, for his tabloid

Daily Mail. The story did wonders for the

circulation figures of the newspaper. It made a small

fortune for Le Queux; there were translations into

twenty-seven languages, and over one million copies of the

book edition were sold.

At that time, however, the

enemy was still France for the British. That was quite

evident from the activities of editors and publishers. Grant

Richards, a successful publisher, commissioned a French

invasion story from Colonel Maude, The New Battle of

Dorking (1900), in

the hope that it would do as well as the original Chesney

story. Again, the editor of Le Monde

Illustré

commisioned Henri de Nousanne to write an end-of-the-British

Empire story, La

Guerre Anglo-Franco-Russe (The Anglo-Franco-Russian

War). That took up

the entire special number of 10 March 1900, complete with

excellent illustrations and a detailed map of the world

which showed how the Russians and the French shared out the

British possessions between themselves. But the scale of

that hopeful history could not compare with the far greater

enterprise that transferred the locations and events in

Wells's War of the

Worlds (without the

knowledge or permission of the author) to a New England

setting in the Boston Post and to the New York area in the

New York Evening

Journal. As David Y.

Hughes has shown in a groundbreaking study, the double act

of brigandage started from the legitimate publication of

Wells's story in the Cosmopolitan (April-December,

1897).14 For the editor of the New York Journal, Arthur Brisbane, that version was

an ideal opportunity to run a serial that would, so he

calculated, send up sales towards the hoped-for million

figure by the simple process of turning the British original

into an all-American affair. The sub-editors on the Journal

got to work--changing the text and adding their own

variations to the original--and on 15 December 1897 their

readers had the pleasure of beginning the serial account of Fighters from Mars:

The War of the Worlds. The process was repeated in the

editing room of the Post, and on 9 January 1898 the

Boston-only version opened as Fighters From Mars: The War of the

Worlds in and Near Boston. This spectacular triumph of

entrepreneurial journalism suggests that two American

editors had to fall back on the pretence of the Fighters from

Mars, because the

United States did not have any enemies able to wage war on

the scale of the conflicts contemplated across the Atlantic.

Their enterprise proved so successful, and the interest in

the most fantastic of future-war fiction so great, that the Journal and the

Post combined for another venture into

the No Man's Land of coming things. They decided to

commission, and they printed six weeks later, a great Yankee

sequel: Edison's

Conquest of Mars by

Garrett P. Serviss. This primitive version of Star

Wars was the most

ambitious and the most way-out future-war story of the

1890s. The trailer in the Post promised the final salvation of

planet Earth:

``Edison's Conquest of

Mars,"

...A Sequel

to...

``FIGHTERS FROM

MARS''

OF EXTRAORDINARY

INTEREST

How the People of All the

Earth, Fearful of a Second Invasion from Mars, Under the

Inspiration and Leadership of Thomas A. Edison, the Great

Inventor, Combined to Conquer the Warlike Planet.

Written in

Collaboration With Edison by Garrett P. Serviss, the

Well-Known Astronomical Author

Edison provides the know-how

for Earth to strike back against the Martians; but the world

has to find the funds to manufacture his electrical ships

and vibration engines by the thousand. The word goes forth

from Washington that all the nations ``must unite their

resources, and if necessary, exhaust all their hoards, in

order to raise the needed sum ...

Negotiations

were at once begun. The United States naturally took the

lead, and their leadership was never for a moment questioned

abroad. Washington was selected as the place of meeting for

a great congress of nations. Washington, luckily, had been

one of the places which had not been touched by the

Martians. But if Washington had been a city composed of

hotels alone, and every hotel so great as to be a little

city in itself, it would have been utterly insufficient for

the accommodation of the innumerable throngs which now

flocked to the banks of the Potomac. But when was American

enterprise unequal to a crisis?15

By the end of the century

the tale of the war-to-come had clearly become a thriving

business that responded to the very different interests of

two sets of readers. In the universe of serious politics and

national defence the short storydeclined in numbers and

vanished from all but the most prestigious magazines, like

the Strand and McClure's Magazine; but the lobbyists for

preparedness continued with their messages, working more

effectively in long stories that often ran to many editions.

In the newer universe of the fancy-free—those who followed

conjecture wherever it led—there were no limits to their

fantasias of the future. One favoured theme was the

scientist of genius and his invention of the superweapon;

and here the delightful excitement that powered these hectic

dramas of the boundless—dynamite ships, immense flying

machines, super-bombs—tends to obscure the beginnings of a

confrontation between science and society.

Jules Verne was the first to

create the Prospero image of the inventor of genius in Nemo

and Robur. His heroes exemplified a confidence in science

and in human capabilities; their theme song could have been

set to the sweet music of progress in Walt Whitman's line:

``Never was average man, his soul, more energetic, more like

a God''(``Years of the Modern,'' 1865). Those sentiments had

once inspired the young Tennyson with great hopes for the

future in his hymn to progress, ``Locksley Hall''; but some

forty-three years later, he had very different thoughts in

his ``Locksley Hall. Sixty Years After'':

- Is there evil but on

earth? or pain in every peopled sphere?

- Well be grateful for the

sounding watchword `Evolution' here.

- Evolution ever climbing

after some ideal good,

- And Reversion ever

dragging Evolution in the mud.

Jules Verne in his old age,

like Tennyson, revised his ideas about the gifts of science.

In Face au

drapeau

(Face the

Flag, 1896) the

invention of the super-bomb, the Fulgurator, is the occasion

for weighing scientific achievement in the scales of good

and evil. Verne went further in his Maître du monde (Master of the World, 1904), where Robur reappears--an

Edison gone wrong--as a danger to the world. In like manner,

the bad genius, ``a mad genius in charge of a new and

terrible explosive,'' dominates the action in Robert

Cromie's The Crack of

Doom (1895). He has

discovered that ``one grain of matter contains enough

energy, if etherized, to raise one hundred thousand tons

nearly two miles'' (36). He sets out to destroy the world,

but fortunately a prototype James Bond defeats him at the

last moment.

Good scientists came singly

or in groups. The example of Ferdinand de Lesseps, for

instance, offered the French ideas for turning the tables on

their hereditary enemy. In George Le Faure's Mort aux Anglais! (Death to the English!, 1892) the good French patriot and

man of genius devises yet another perfect scheme to defeat

the British: reverse the Gulf Stream and freeze them out! An

even more ingenious variant on that notion comes from

Alphonse Allais who devotes the aptly named Projet d'attitude inamicale

vis-à-vis de l'Angleterre (Plan for Hostile Relations against

England, 1900) to a

plan for freezing the Gulf Stream. The Channel then ices

over ten feet deep and the French march across to final

victory.

Other operations for the

good of the nation or of humankind were the work of secret

international brotherhoods like the dedicated anarchists in

George Griffith's The

Angel of the Revolution. That tale of terror began in

January 1893 as a serial in the new British tabloid, Pearson's

Weekly; it ran

through 39 instalments; and worked through the contemporary

schedule of super-weapons from compressed air guns to fast

aerial cruisers. Good here triumphs over evil: the

Franco-Russian forces are defeated; and the AngloSaxon

Federation of the World is proclaimed. This happy notion of

the Anglo-Saxon Conquest of the world appeared in a scenario

that had similar scripts on both sides of the Atlantic. In

G. Danyer's Blood is

Thicker than Water (1895) a British writer reckoned the

Americans and the British had so much in common that the two

nations would inevitably become the policemen of the world;

they would intervene in a war between France and Germany;

and would finally come together in a grand fraternal

union:

...all will be

equal in the brotherhood of their race, and over all will

float, as against the rest of the world, a common flag,

which, hoisted when danger threatens, will be the signal for

the rally for a common object of every force that can be

disposed of by the greatest union of which history makes

mention. (158-59)

An American version of these

world ambitions appeared in B.R. Davenport's Anglo-Saxons Onward! A Romance of the

Future (1898), where

an American author looked forward to an alliance between

Americans and British against the Russians and the Turks. As

the President of the United States told the Senate when he

presented the Treaty of Alliance between the two

nations:

...the fact that

Great Britain was America's only natural ally, that any

circumstance tending to weaken the English nation was

pregnant with danger to the influence and welfare of the

Anglo-Saxon race all over the world, and consequently an

attempt upon Great Britain was full of dire consequences to

the Republic as the other great Anglo-Saxon nation.

(257)

These final solutions for

the problems of war and peace must have owed something to

Andrew Carnegie who had argued for an Atlantic alliance in

his tract on ``The Reunion of Britain and America'' in 1893.

Indeed, the idea that the future belonged to the

Anglo-Saxons was in the air about the turn of the century.

It was central to Wells's forecast in Anticipations (1902) where he showed himself

convinced that:

...a great

federation of white English-speaking peoples, a federation

having America north of Mexico as its central mass (a

federation that may conceivably include Scandinavia) and its

federal government will sustain a common fleet, and protect

or dominate or actually administer most or all of the

non-white states of the present British Empire, and in

addition much of the South and Middle Pacific, the East and

West Indies, the rest of America, and the larger part of

black Africa. (260-61)

When Wells was engaged on

his Anticipations in 1901, he saw no connection

between the Navy Law of 1898, which began the construction

of a large German navy, and the increased possibility of a

great European war. The first signs of a possible

Anglo-German confrontation, however, had already appeared

in: T.W. Offin, How

the Germans took London (1900); and in Karl Eisenhart, Die Abrechnung mit

England

(The Reckoning with

England, 1900). The

German writer describes the war-to-come against the United

Kingdom; and he begins by saying that ``The entire Navy had

long yearned for the Day when they could take on the hated

English; for they had brought on themselves immense hatred

and an animosity like that which the French had experienced

in 1813.''16 That was the signal for a great

outpouring of tales about the coming war between the British

and the Germans. For the following fourteen years, British

writers described a German invasion of England in tales

like: The

Invaders, The Invasion of

1910, The Enemy in our

Midst, The Death

Trap; and German

writers gave their version of der nächste

Krieg in their

visions of: Der

Weltkrieg: Deutsche

Träume, Die `Offensiv-Invasion' gegen England, Deutschlands Flotte im

Kampf.17 All these essays in future-think had

two things in common: the authors expected a war between the

Imperial Reich and the United Kingdom; and in their

descriptions of naval and military engagements they failed

entirely to foresee the new kind of warfare that began in

the autumn of 1914.

NOTES

1. For a survey of early

future-war stories, see I.F. Clarke, ``Before and After The Battle of

Dorking,'' SFS, 24:34-46, March 1997.

2. Jack London, ``The

Unparalleled Invasion,'' Excerpt from Walt. Nervin's

``Certain Essays in History,'' McClure's Magazine (July 1910), 308-14 and reproduced

in: I.F. Clarke (ed), The Tale of the Next Great War,

1871-1914 (Liverpool: Liverpool UP, 1995),

265.

3. Ibid., 269. London's

story has been chosen as one of the texts to be used by

students of English in the Central China Normal University

at Wuhan, Hubei, People's Republic of China.

4. These British naval

stories became a flood in the 1890s--an effect of the

interest in many new types of warship and of the increasing

tension between the United Kingdom and France, the only

comparable naval power at that time. The major stories were:

William Laird Clowes, The Captain of the``Mary

Rose,'' 1892; A.N.

Seaforth (George Sydenham Clarke), The Last Great Naval

War, 1892; Captain

S. Eardley-Wilmot, The Next Naval War, 1894; The Earl of Mayo, The War Cruise of the

Aries, 1894; J. Eastwick, The New

Centurion, 1895;

F.T. Jane, Blake of

the ``Rattlesnake,''

1895; Francis G. Burton, The Naval Engineer and the Command of

the Sea, 1896;

H.W.Wilson and A. White, When War breaks out, 1898;

P.L.Stevenson, How the Jubilee Fleet

escaped Destruction, and the Battle of

Ushant, 1899.

5. Capitaine Danrit, La Guerre des forts:

Grand Récit Patriotique et Militaire (Paris: Fayard, 1900), 14. All

translations from French and German have been made by the

author.

6. See ``Danrit, Capitaine''

in Pierre Versins, Encyclopédie de l'Utopie...et

de la Science Fiction (Lausanne: L'Age d'homme, 1972),

222-23.

7. Quoted in Paul Usherwood

& Jenny Spencer-Smith, Lady Butler. Battle Artist,

1846-1933 (London:

National Army Museum, 1877), 166. This survey gives an

excellent acount of Lady Butler's paintings. The influence

of Meissonier is examined in the chapter entitled ``The

Influence of French Military Painting,'' 143-66.

8. C. De W. Willcox,

``Changes in Military Science'' in The 19th Century: A Review of

Progress (London and

New York: G. P. Putnam, 1901), 492-93.

9. Albert Robida, La Guerre au

vingtième siecle, translated in I.F. Clarke (ed.), The Tale of the Next

Great War, 1871-1914

(Liverpool: Liverpool UP, 1995), 94.

10. Ibid., 99. My thanks to

Marc Madouraud of Villiers-Adam for the

illustrations.

11. B.H. Liddell Hart, History of the First

World War, 1970

(London: Pan Macmillan, 1992), 28.

12. Charles Richet, Dans cent

ans (Paris: Paul

Ollendorff, 1892), 62-3.

13. ``Has War Become

Impossible?'' in Review of Reviews: Special

Supplement, xix,

Jane-June, 1899, 1-16. Bloch began his study of modern

warfare in 1888. The book was first published in Russia in

1897, then in France and Germany in 1898. An abridged

English translation appeared in 1900: W.T.Steed (ed.), Modern Weapons and

Modern War (London:

``Review of Reviews'' Office, 1899).

14. The full, fascinating

story appears in: David T. Hughes. ``The War of the Worlds in the Yellow Press,''

Journalism

Quarterly, 43, 4

(Winter 1966), 639-646.

15. Garrett P. Serviss, Edison's Conquest of

Mars, with an

introduction by A. Langley Searles, Ph.D. (Los Angeles:

Carcosa House, 1947), 16.

16. Karl Eisenhart, Die Abrechnung mit

England (Munich:

Lehmann, 1900), 3.

17. Publication details for

these works are as follows: Louis Tracy, The Invaders (London: Pearson, 1901); William Le

Queux, The Invasion

of 1910 (London: E.

Nash, 1906); Walter Wood, The Enemy in our

Midst (London: J.

Long, 1906); Robert William Cole, The Death Trap (London: Greening, 1907); August

Niemann, Der

Weltkrieg-Deutsche Träume (Leipzig: F.W. Bobach, 1904); Karl

Bleibtreu, Die `Offensiv-Invasion' gegen England (Berlin: Schall & Rentel, 1907);

F.H. Grautoff, Deutschlands Flotte im

Kampf (Altona: J. Hrder, 1907).

Back to Home Back to Home

|

|

|