Leaders the World Needs

is a regular feature of DePauw Magazine, which is published three times a year.

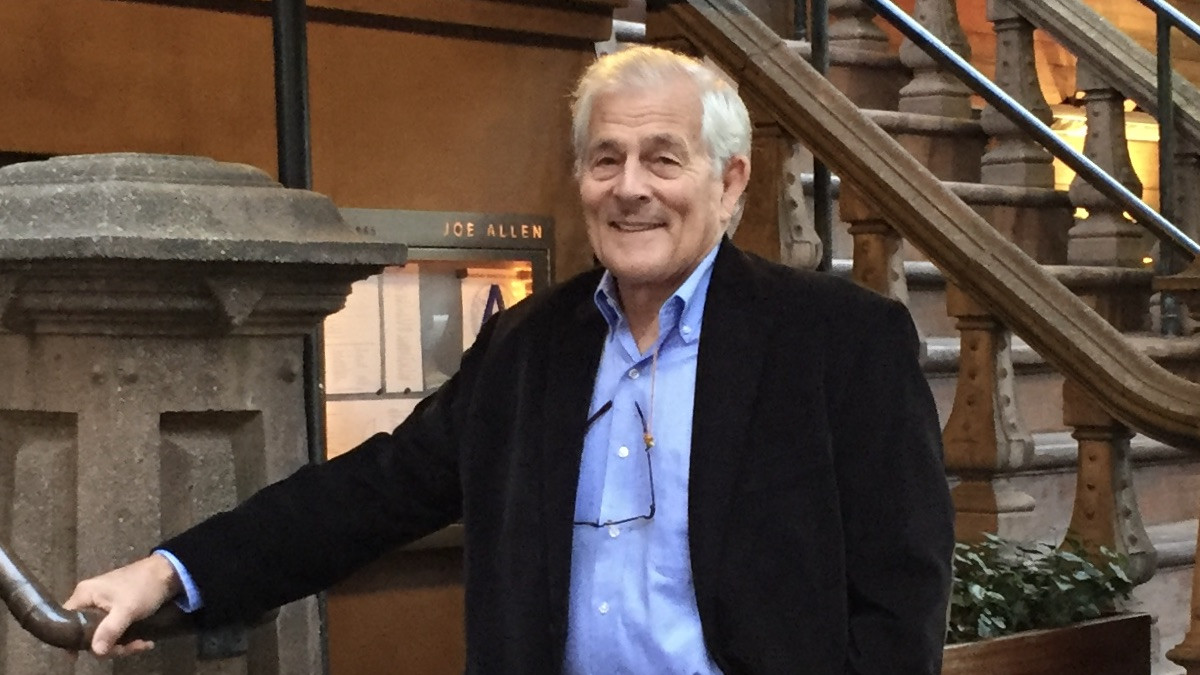

David T. Allen ’61 was a newly minted physician, working as a pediatric intern at Palo Alto-Stanford Hospital in 1966, when he was sent to Guatemala to draw blood from indigenous people.

Polio had ravaged the United States less than two decades earlier, then dramatically curbed in the mid-1950s when Jonas Salk developed a vaccine. The disease did not seem to affect people in the developing world, and Allen’s work was intended to decipher if Guatemala’s people had an antibody that made them immune.

Polio had ravaged the United States less than two decades earlier, then dramatically curbed in the mid-1950s when Jonas Salk developed a vaccine. The disease did not seem to affect people in the developing world, and Allen’s work was intended to decipher if Guatemala’s people had an antibody that made them immune.

It was not easy. At the time, the indigenous people believed they were born with a finite volume of blood that was not replenished and thus “they were not willing donors,” Allen said. He regularly traded medical care for a test tube of blood. The experience demonstrated that “belief systems trump everything,” and Allen sees that happening again with COVID-19. “When you have a situation like this particular epidemic and you then are trying to explain to people how transmission works and they have a belief system that discounts it, it’s very difficult to get people to change behavior,” he said.

He knows what he is talking about. After that internship, he joined the Epidemic Intelligence Service, part of the Centers for Disease Control, where for three years he traveled to nine developing countries to combat malaria and promote maternal health. That led to health positions of escalating authority in Tennessee’s state government until July 1980, when he was named Kentucky’s health commissioner, a position he held more than three years. He next went into private practice until December 1987, when he was appointed health director of the Louisville and Jefferson County Health Department.

"When you have a situation like this particular epidemic and you then are trying to explain to people how transmission works and they have a belief system that discounts it, it’s very difficult to get people to change behavior."– David T. Allen '61

He was on the new job less than two months when Louisville experienced an outbreak of hepatitis A; it eventually sickened 240 people and killed three. Allen led the investigation to find the cause, checking the public water supply, workplace drinking fountains and ice machines and restaurants. Meanwhile, his department undertook a massive public education campaign, plastering public washrooms across the county with half a million “wash your hands” signs. It ultimately was determined the culprit to be a truckload of contaminated iceberg lettuce distributed to several Louisville restaurants.

Allen later returned to the private sector, working on the corporate side and practicing medicine, so his 50-year career, he said, was split equally between public health and private practice. He volunteered his services in Haiti after the devastating 2010 earthquake and for 14 years did a monthly medical segment on a Louisville television station. Until he turned 79 in spring 2019, he worked several shifts a month at a Baptist Health Urgent Care clinic. And he has many thoughts about what should be done to slow the spread of COVID-19. (“We need to do the strictest social distancing and then we need to get into the field just literally millions of tests and identify who is in the infected but asymptomatic population, because that’s the real key to spread,” he said.)

It all amounts to “an incredibly blessed career,” Allen said. “I’ve had a wonderful time. I have a wonderful family. What more can you ask?”

DePauw Magazine

Summer 2020

The Bo(u)lder Question

The Bo(u)lder Question  Retired archivist reflects on 36 years as DePauw’s memory keeper

Retired archivist reflects on 36 years as DePauw’s memory keeper First Person by Connie Campbell Berry '67

First Person by Connie Campbell Berry '67 First Person by Wayne Glausser

First Person by Wayne Glausser Battling an epidemic, treating individuals: Physician alum has done it all

Battling an epidemic, treating individuals: Physician alum has done it all  Welcome, Class of 2024!

Welcome, Class of 2024! She has loved them since she was 6: vet cares for, competes with and rescues horses

She has loved them since she was 6: vet cares for, competes with and rescues horses Liberal arts taught wildlife vet to consider different approaches to patients’ problems

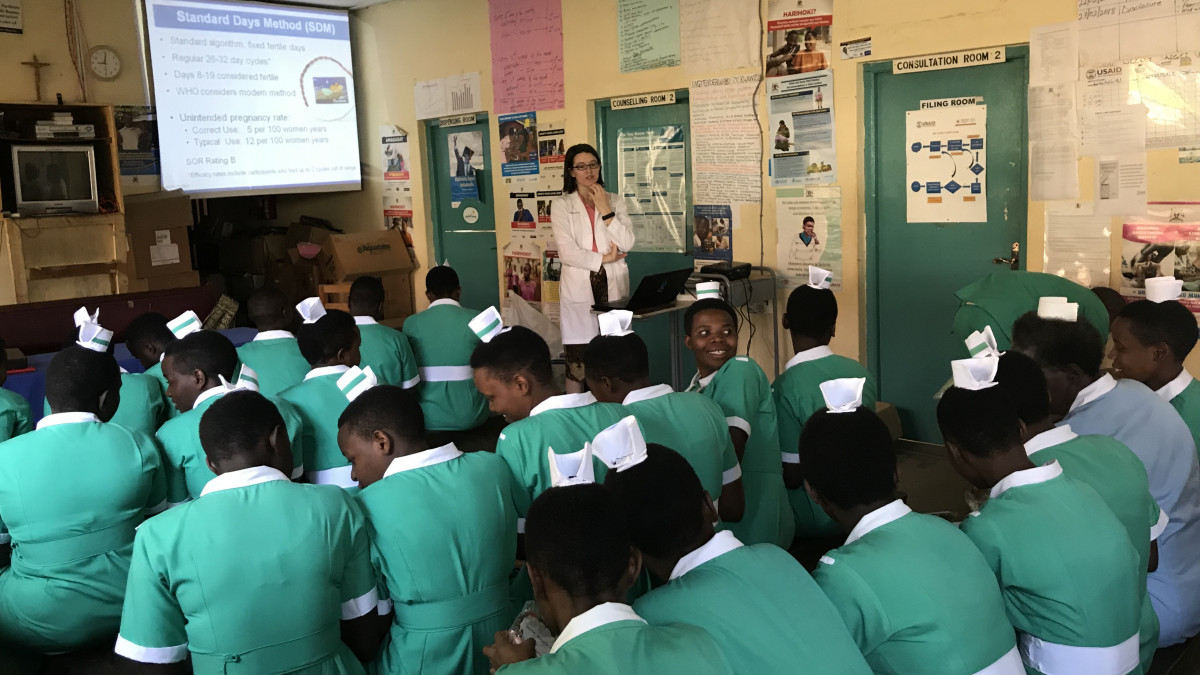

Liberal arts taught wildlife vet to consider different approaches to patients’ problems Scientist and humanitarian: Prof embodies disparate interests, then acts on and teaches them

Scientist and humanitarian: Prof embodies disparate interests, then acts on and teaches them Researcher follows the science toward treatments

Researcher follows the science toward treatments The ‘dura mater’ handles medical training and motherhood with aplomb

The ‘dura mater’ handles medical training and motherhood with aplomb  Evolving interests drive ’12 grad to trade test tubes for a stethoscope

Evolving interests drive ’12 grad to trade test tubes for a stethoscope Alum hopes to meet global needs by establishing med school

Alum hopes to meet global needs by establishing med school The healers

The healers Personal experiences prepared ’76 alum for work, service

Personal experiences prepared ’76 alum for work, service DePauw in the time of COVID-19

DePauw in the time of COVID-19 DePauw’s new president: A ‘visionary,’ empathetic and focused optimist ... who sings

DePauw’s new president: A ‘visionary,’ empathetic and focused optimist ... who sings

DePauw Stories

A GATHERING PLACE FOR STORYTELLING ABOUT DEPAUW UNIVERSITY

Browse other stories

-

Athletics

-

Women's Golf - Williams Selected NCAC Women's Golf Athlete of the Week

-

Men's Golf - Tigers Finish 12th at Music City Shootout; "B" Team Places Fifth

-

Women's Golf - DePauw Wins Music City Shootout

More Athletics

-

-

News

-

Francesca Seaman Speaks the Language of Mentorship

-

DePauw Announces $10 Million Matching Challenge for Student Scholarships

-

DePauw University Remembers Esteemed President Emeritus Robert G. Bottoms

More News

-

-

People & Profiles

-

Empie, Party of Five: One Family’s Unique DePauw Bond

-

Entrepreneurs Eric Fruth ’02 and Matt DeLeon ’02 Are Running More Than a Business

-

Rick Provine Leaves Legacy of Leadership and Creativity

More People & Profiles

-

-

Have a story idea?

Whether we are writing about the intellectual challenge of our classrooms, a campus life that builds leadership, incredible faculty achievements or the seemingly endless stories of alumni success, we think DePauw has some fun stories to tell.

-

Communications & Marketing

101 E. Seminary St.

Greencastle, IN, 46135-0037

communicate@depauw.eduNews and Media

-

News media: For help with a story, contact:

Bob Weaver, Senior Director of Communications.

bobweaver@depauw.edu.