You’ve heard the clichés since childhood: Think hard. Put your mind to it. Wear your thinking cap.

Apparently Mom was right – or, at least, early evidence from a research study being conducted by a DePauw University professor and his students suggests so. It appears that, when an ethical decision is considered, those who put more mental energy into the task are more likely to decide ethically. Those with low self-control are more likely to make an unethical decision.

Many more experiments must be conducted and many ethical questions must be considered before definitive statements can be made, findings can be verified and practical ways to use the work can be identified. But the work by Robert West, a neuroscientist and the Elizabeth P. Allen distinguished university professor, and his students already is attracting international attention.

West, who came to DePauw in fall 2015 in part to create a new neuroscience major, has expanded on two experiments that he had conducted with a colleague at Iowa State University. There, West and the colleague, who worked in information systems, wanted to find out what happens in the brain when people decide to commit cybercrimes, which cost the world economy $3 trillion – yes, that’s with a “t” – in 2015 and are expected to cost $6 trillion by 2021.

West’s work at DePauw constitutes a third experiment, on which he collaborated with Emily Budde ’18, starting with her 10-week summer research experience in 2016 and, except for the following summer, until she graduated in May.

“Right now we’re at the point where we’re trying to understand what’s going on when you’re making those decisions,” West says. “What are some of the variables that might modulate that? And so, 10 years from now, we might actually be able to make a recommendation.”

The first goal of the research at DePauw was to reproduce the effects found at Iowa State in a new environment. West and Budde also sought to learn if eliminating an aspect of the first two experiments that raises ethical concerns for some – deception of the subjects – would make a difference in the results. The subjects in Iowa were told that a survey they completed established a personality profile and that their stipends would be higher if their responses during the research were consistent with the profile. That wasn’t true, West says, but the researchers used the deception – which is considered acceptable by some researchers as long as it is ultimately revealed – to motivate subjects to answer candidly, even when doing so revealed their willingness to make an unethical decision.

At DePauw, the subjects were encouraged to answer the questions as honestly as they could while pretending to be someone else. “We got rid of the deception and still basically got the same data,” West says.

They also introduced several new concepts: Did the time span between a decision and the anticipated result matter? Did it matter who benefited from the decision – the person making it or someone else? And did one’s self-control, impulsivity and willingness to take risks – determined by the volunteer subjects’ responses to questions about the likelihood that they would engage in certain activities – affect the results?

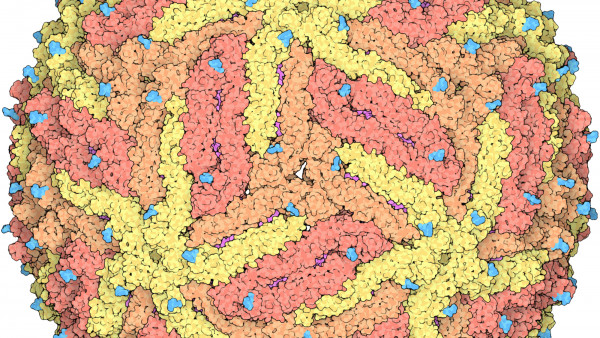

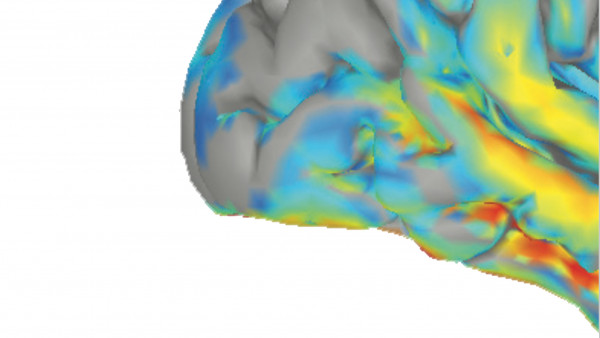

For the experiment, 40 subjects – students, faculty and staff – worked a saline gel into their scalps and donned headgear resembling a swim cap. As the subjects completed a questionnaire that posed ethical questions, 32 electrodes measured activity in the medial prefrontal cortex and the temporoparietal junction parts of their brains.

“Within about a fifth of a second to a half of a second after the person starts thinking about this, making one of these decisions, this region seems to be active,” West says. Less brain activity occurred when a subject made an unethical decision, apparently because he or she was “not spending the brain energy to do the work of making the correct decision.”

West and Budde noted that the effects did not occur when the subject was making a less consequential decision, such as whether to attend a ballgame. “It’s only when you’re making a decision about doing something you shouldn’t be doing,” West says. “It’s not simply the act of having to weigh a decision.”

Budde, who performed much of the hands-on work with subjects, came to DePauw and its Science Research Fellows program with an interest in psychology. One class with West, she says, convinced her that she should study social neuroscience, and the lab experience afforded her as a research fellow has been a plus.

Budde did research last summer in her hometown at the University of Cincinnati. She landed the position through networking enabled by the fellows program – one of its benefits, says Michael Roberts, chair of DePauw’s Psychology and Neuroscience Department.

“This level of research engagement is unusual and exemplary,” he says. “It is terrific preparation and makes our students stellar candidates for top graduate and professional programs.”

Budde has been accepted to graduate school for the fall, where she hopes to figure out if she prefers academia or applied research psychology.

Though it is premature to drawn too many conclusions, the work generated interest and garnered news coverage when West and his Iowa State colleague submitted a paper in June 2017 for a survey of the social and behavioral science for national security conducted by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine.

The paper concluded that the work “has the potential to provide insight into violations of (information security) by organizational insiders and to also identify processes or procedures that may serve to mitigate insider threat to organizational InfoSec.”

West presented another paper, co-authored by science research fellows Kaitlyn Malley ’19 and Bridget Kirby ’20, at the NeuroIS Retreat in Vienna in late June 2018. Early that month, Kirby presented the work at the Interdisciplinary Symposium on Decision Neuroscience at the University of Michigan.

Given the extent of cybercrime, any mitigation would be significant, West says. He also wants to learn whether the findings apply to other fields – say, police work or journalism.

It’s too early to know, he says, if hiring managers will someday use brain activity to determine if a candidate will be a good hire or criminal investigators will be able to determine if a suspect is likely to commit a crime – and whether the law and society will accept such uses. But he warns that businesses already use questionnaires to screen prospective employees, even though such uses are not necessarily validated by evidence.

That’s just one of the ethical gray areas related to West’s research about ethical decision-making.

“For me,” he says, “the ethical piece is, don’t put the cart before the horse, No. 1. No. 2, you can’t jump from basic science to translational science in months or years. It doesn’t happen. I’m sorry; I know the world wants that but it doesn’t happen.”

To learn more about the way ethics is taught at DePauw University, read the summer 2018 issue of DePauw Magazine, available at https://www.depauw.edu/offices/communications-marketing/depauw-magazine/.

DePauw Magazine

Summer 2018

Art and science and serendipity

Art and science and serendipity Encouraging an ethical ethos

Encouraging an ethical ethos Front & center

Front & center Prindle’s Purpose

Prindle’s Purpose Ethics in disciplines

Ethics in disciplines Your brain on ethics

Your brain on ethics

DePauw Stories

A GATHERING PLACE FOR STORYTELLING ABOUT DEPAUW UNIVERSITY

Browse other stories

-

Athletics

-

Women's Swimming & Diving - DePauw Sets Two New Pool Records Against #11 WashU

-

Men's Swimming & Diving - Tigers Finish 102-204 Against #12 WashU in Dual-Meet

-

Men's Track & Field - Tigers Finish Fourth at Rose-Hulman Classic

More Athletics

-

-

News

-

DePauw University Remembers Esteemed President Emeritus Robert G. Bottoms

-

Student and Professor Share Unexpected Writing Journey

-

Four in a Row! DePauw Wins 131st Monon Bell Classic

More News

-

-

People & Profiles

-

Entrepreneurs Eric Fruth ’02 and Matt DeLeon ’02 Are Running More Than a Business

-

Rick Provine Leaves Legacy of Leadership and Creativity

-

History Graduate Cecilia Slane Featured in AHA's Perspectives on History

More People & Profiles

-

-

Have a story idea?

Whether we are writing about the intellectual challenge of our classrooms, a campus life that builds leadership, incredible faculty achievements or the seemingly endless stories of alumni success, we think DePauw has some fun stories to tell.

-

Communications & Marketing

101 E. Seminary St.

Greencastle, IN, 46135-0037

communicate@depauw.eduNews and Media

-

News media: For help with a story, contact:

Bob Weaver, Senior Director of Communications.

bobweaver@depauw.edu.