Ethics in disciplines

KHADIJA STEWART

ON COMPUTER SCIENCE ETHICS:

Computer science students internalize ethical behaviors because many have experienced violations, says Khadija Stewart, associate professor of computer science.

“We talk about malware a lot,” she says. “They are aware of how personally they can be affected with that, whether the piece of malware does something damaging to their data or whether it simply turns the camera on and watches them.”

Ethics discussions bookend computer science majors’ time at DePauw. First-year students undertake exercises that require ethical decisions while seniors study the Association of Computing Machinery’s code of ethics, which calls for computer professionals to, among other things, honor copyrights and patents; give proper credit for intellectual property; and respect privacy.

Impromptu discussions about ethics also occur often, the result of Stewart’s request that students raise topics during each class period. “Often,” she says, “they will bring up an ethical issue that we discuss in class.”

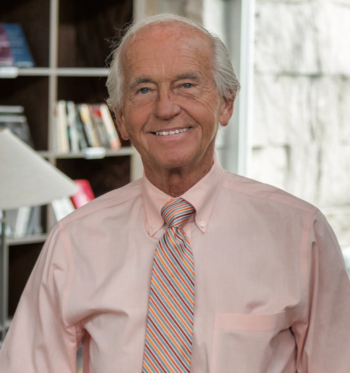

JEFFREY MCCALL

ON JOURNALISM ETHICS:

The proliferation of media outlets and formats has eroded some journalists’ ethics, says Jeffrey McCall, professor of communication and theatre.

“They all have to get their audiences or their clicks or their ratings or whatever (so) they’ve all got to do something to distinguish themselves,” resulting, he says, in “less compelling responsibility among the journalists themselves to say, ‘I’ve got to do it fairly; I’ve got to do it right.’”

The news industry “needs to come to a reckoning here and figure out maybe the way we’re going about news in this day and age is maybe not keeping people engaged. And we need to think about what we can do. . . There’s a role in education, both secondary education and certainly higher education, to reach out and convince young people now who are becoming bystanders that that’s not healthy for them or for our nation – that things are going on that affect them and they might well pay more attention.”

TED BITNER

ON MEDICAL ETHICS:

Recognizing that different people and different cultures have different ethical standards, Ted Bitner, the Hampton and Esther Boswell distinguished university professor of psychology, teaches Honor Scholar students to approach ethical decisions with a consistent methodology.

First, he says, they must identify the moral dilemma. And then they must ask a lot of questions. In end-of-life decisions, for example, is the dying person’s autonomy threatened? If she left a directive, is there a compelling reason to countermand it? Are medical procedures made possible by new technology ethical? Is it ethical for a patient to go to another country where a needed organ is more readily available, perhaps because someone will sell it? Is extending life, no matter what, always ethical?

“People have different views because of their own value system,” says Bitner, also the scientific research coordinator for the Prindle Institute. “We have to be very careful with the students to help them understand that, just because we have this value, just because we have this moral behavior, doesn’t really make it moral.”

Beside: Kevin Kinney keeps his (required) distance from a land iguana in the Galapagos Islands.

KEVIN KINNEY ON THE ETHICS OF ECOTOURISM:

Sixteen people on an airplane. The 70-foot, diesel-fueled touring boat. Electricity. Fresh water. Shipped-in food. The risk of inadvertently bringing in pathogens.

Humans cannot visit the Galapagos Islands 600 miles off the coast of Ecuador without stressing them, even damaging them, biology professor Kevin Kinney says. It’d be nice if visitors followed the ecotour mantra of “take nothing but pictures and leave nothing but footprints,” he says. Better still if nobody visited at all.

But that’s not realistic, and Kinney recognizes the ethical dilemma and opts to take students to the islands that inspired Darwin’s theory of natural selection “because I want them to see this and I want them to think about these issues. . . We’re doing damage when we go down there but there’s nothing to substitute for the firsthand experience of being there.”

Kinney expects his Winter Term students to return from their experience proselytizing about preserving the Galapagos and the environmental issues they illustrate.

“I’ve had students who have come back and changed their career arc and wanted to go into more environmental studies because they saw what was going on,” he says. A couple became vegetarians. He hopes those who are not immediately moved will reflect on the experience and ultimately make eco-friendly choices in their lives.

“You can show them videos and show them pictures” but students are more likely to respond “when they see an animal, when they see the bones of a marine iguana and realize this animal died because of an El Niño year, when it was very dry on the islands. And then they start to think, well, is that El Niño something that we had a hand in? And then they start to realize this is life or death for these organisms. When they start to realize that, that’s a big moment.”

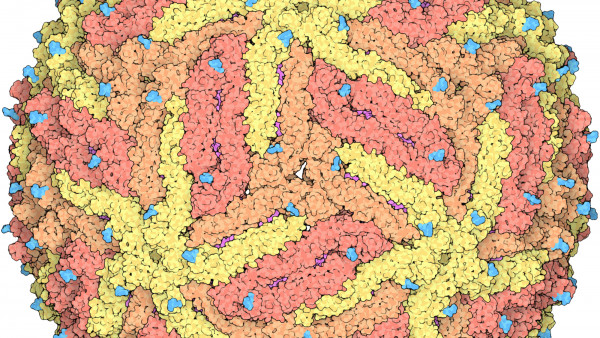

PASCAL LAFONTANT

PASCAL LAFONTANT

ON ETHICS OF GENE MANIPULATION:

Pascal Lafontant was aware of the ethical dilemmas presented by the cutting-edge CRISPR technology when a colleague from Harvard Medical School visited DePauw for four days in April to teach students and professors how to use it to excise problematic genes from the human genome.

“I felt we needed to have an ethical component” so he arranged a discussion about the ethical questions prompted by CRISPR, which holds the promise of curing dread diseases but also raises the specter of eugenics – creation of designer babies or pursuit of a master race.

“To me, those are discussions that need to happen,” Lafontant says. “Those are discussions that are happening.

And not just about CRISPR, says Lafontant, who thinks about ethics in his research on fish. For example, when he performs surgery on a fish, the subject is anesthetized and surgery is done in a room separate from the general population of his lab.

“I definitely want to make sure,” he says, “that when we’re doing our work we’re conscious about the ethical issue involved.”

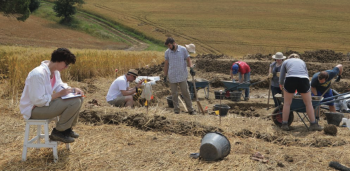

Beside: Rebecca Schindler, left, makes notes as her students and colleagues work at the Gioiella-Vaiano site in central Italy.

REBECCA SCHINDLER

ON ETHICS IN ARCHEOLOGY:

Archeological ethics are “challenging and intellectually engaging because there aren’t necessarily right answers,” says Rebecca Schindler, a classical studies professor. “It’s always contextually dependent on what your goal is and what your values are.”

So Schindler asks her students a lot of questions: Should a monument that humans intentionally destroy be reconstructed for educational purposes? Does authenticity matter? How will future archeologists study such a site?

It’s easy, she says, for students to condemn collectors or museums that pay huge sums for artifacts, incentivizing looters to rob graves, but it’s a more difficult question if the seller, displaced by war, is doing whatever he can to feed his family. When students fret that archeological sites were flooded when Turkey built dams to generate hydroelectric power, she asks them, “how could you possibly let a million people go without electricity?”

In Schindler’s “Who Owns the Past?” class, students consider the ethics of archeological research; handling artifacts, the art market; and displaying material culture from the past.

And at an excavation site in central Italy, where Schindler and her colleague/husband Pedar Foss, also a classical studies professor, arrived with six students in late May for a fourth DePauw expedition, students are encouraged to “be really conscientious of the implications of their work” – not just its contribution to knowledge but also its effects on the community.

At the dig in Comune di Castiglione del Lago, that means listening to locals and consulting them about what they want for their museum, the repository of artifacts recovered from the site, she says.

“Archeologists used to shun local knowledge, like we’re the experts,” she says. “But we’ve tried to embrace it. We try to listen to what everybody tells us about the area because everybody has a story that they want to tell . . .

“The ethical question is, whose story do we value? There’s more than one way to tell the story of the site.”

DePauw Magazine

Summer 2018

Art and science and serendipity

Art and science and serendipity Encouraging an ethical ethos

Encouraging an ethical ethos Front & center

Front & center Prindle’s Purpose

Prindle’s Purpose Ethics in disciplines

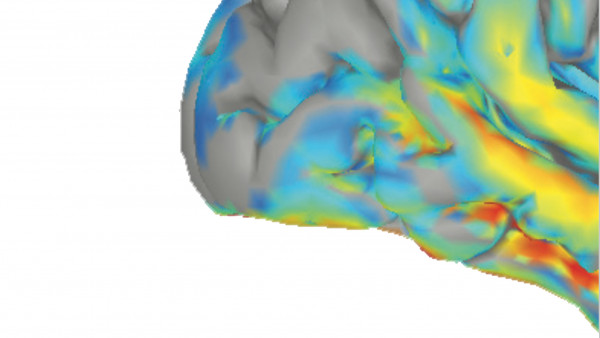

Ethics in disciplines Your brain on ethics

Your brain on ethics

DePauw Stories

A GATHERING PLACE FOR STORYTELLING ABOUT DEPAUW UNIVERSITY

Browse other stories

-

Athletics

-

Women's Swimming & Diving - DePauw Sets Two New Pool Records Against #11 WashU

-

Men's Swimming & Diving - Tigers Finish 102-204 Against #12 WashU in Dual-Meet

-

Men's Track & Field - Tigers Finish Fourth at Rose-Hulman Classic

More Athletics

-

-

News

-

DePauw University Remembers Esteemed President Emeritus Robert G. Bottoms

-

Student and Professor Share Unexpected Writing Journey

-

Four in a Row! DePauw Wins 131st Monon Bell Classic

More News

-

-

People & Profiles

-

Entrepreneurs Eric Fruth ’02 and Matt DeLeon ’02 Are Running More Than a Business

-

Rick Provine Leaves Legacy of Leadership and Creativity

-

History Graduate Cecilia Slane Featured in AHA's Perspectives on History

More People & Profiles

-

-

Have a story idea?

Whether we are writing about the intellectual challenge of our classrooms, a campus life that builds leadership, incredible faculty achievements or the seemingly endless stories of alumni success, we think DePauw has some fun stories to tell.

-

Communications & Marketing

101 E. Seminary St.

Greencastle, IN, 46135-0037

communicate@depauw.eduNews and Media

-

News media: For help with a story, contact:

Bob Weaver, Senior Director of Communications.

bobweaver@depauw.edu.