You might be surprised to learn that Daniel Mendoza was in his senior year at DePauw University and had not identified a major.

But don’t assume that this is the story of some indecisive slacker, some ne’er do well. Mendoza – who did graduate in 2001 – is anything but.

But don’t assume that this is the story of some indecisive slacker, some ne’er do well. Mendoza – who did graduate in 2001 – is anything but.

Call him a Renaissance man. A jack of a lot of trades and, yes, a master of many. A polymath.

He is a prolific scientist with the sensibility of a policymaker and the skills of a diplomat. He is a former competitive cyclist who now competes in snowshoe races and duathlons. If Mendoza has a problem, it is that he has too many interests.

He acknowledges that that created some issues when he was at DePauw. As the offspring of two scientists – an agronomist father and a physicist/mathematician mother – Mendoza was determined not to follow in their footsteps, he said. As he was growing up in his native Peru – with a detour of several years in Nairobi, Kenya, where his father worked for the United Nations Environment Programme – he decided to study chemistry.

“I actually bounced around the sciences a lot,” he said. “I would take several courses in one major and then I would bounce to another major and by my senior year I was basically 80% of the way through four majors.”

“I just wanted to learn a lot. I was just really curious and I was just really happy to be here.”– Daniel Mendoza

Everything scientific interested him – so much so that he double-booked classes. Registration was not computerized in those days, so he got away with it. “I would have classes at the exact same schedule and I would just alternate between which ones I went to. I was averaging, I think, 21 credit hours,” as opposed to the traditional 16.

“I just wanted to learn a lot,” he said. “I was just really curious and I was just really happy to be here.”

He managed to hold down his expenses for texts by borrowing each one from the library for the allotted two hours. “I would actually force myself to get all the reading and all the homework done in those two hours. Just once a week and that was it,” he said.

He saved time and money, enabling him to socialize, pursue athletics (he was the pusher for Sigma Nu’s Little 5 team his first year, then rode for the next three) and work 30 hours a week. His grades were another story.

He saved time and money, enabling him to socialize, pursue athletics (he was the pusher for Sigma Nu’s Little 5 team his first year, then rode for the next three) and work 30 hours a week. His grades were another story.

“I barely got a 2.8,” he acknowledged. And then, in his senior year, there was that problem of no major. Computer science professor Gloria Townsend “sat me down and said, ‘OK, you have to graduate with a major.’ Because I was basically only two classes away from a chemistry or a math major. But then I wanted to really focus more on physics and computer science. …

“I always tell everyone that Gloria saved my life. She basically helped guide me and she was very real. She was saying ‘you’re screwing up; you have a lot of talent and you can do this.’ And that kind of mentorship, that kind of guidance, that kind of caring you don’t see in a large university.”

Townsend remembers telling Mendoza, “You can't do everything. You have to focus. If you water yourself down, you will be mediocre in a large number of areas and will not be able to make the world a better place. …

“When he was a teenager, Danny's ability to see the world differently from the way others see it distinguished him.”

"Danny's ability to see the world differently from the way others see it distinguished him.”– Gloria Townsend

As right as Townsend was about his abilities, he has proven her wrong in one way: Though he focuses on plenty, he is rarely mediocre. He ended up graduating with two majors and two minors. He got a master’s degree in physics and a Ph.D. in Earth and atmospheric sciences at Purdue University. As he was completing his doctorate, “I realized that about 50% of people believe in climate change; about 100% percent believe in lung cancer,” precipitating “my left turn, as I like to call it, into health.”

At Purdue, he studied air pollution and greenhouse gases, and measured carbon monoxide emissions from specific sources in specific locations – a particular building or an exact spot along a road – in Indianapolis. As a postdoctoral fellow at the University of South Florida, he researched road-source emissions that are known to damage health.

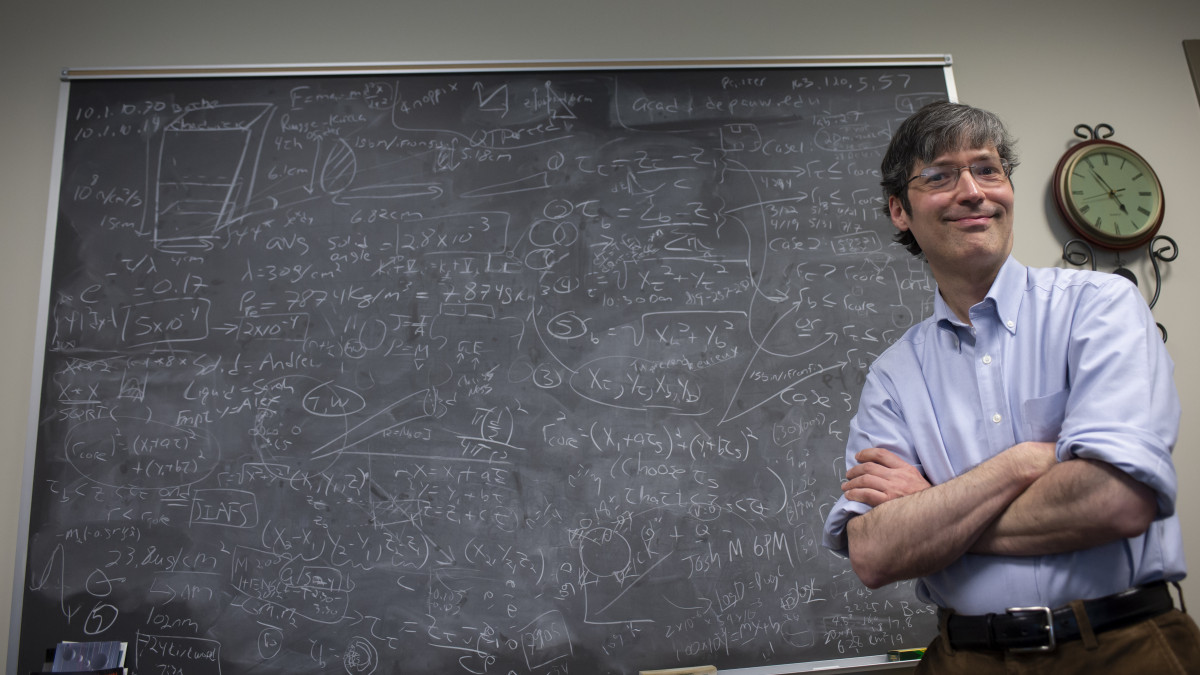

He moved in 2014 to the University of Utah, where he is a research assistant professor in the atmospheric sciences department, a visiting assistant professor in city and metropolitan planning and a postdoctoral fellow in the medical school’s pulmonary division. He has expanded his research to study the atmospheric transport of pollutants and gene-environment interaction – that is, how gene mutations can make some individuals especially susceptible to a pollution-related illness.

“We need to put a face on this,” Mendoza said. “So a lot of the work that I do is focused on vulnerable populations, and the easiest population to really track down and that everyone can relate to is children.” He recently submitted a research paper for publication in which he assesses the impact of pollution on school absenteeism. Because he understands that lawmakers – those with the power to regulate emissions – respond more to dollar signs than heart strings, he expresses that impact in costs: a school district’s loss in state funding when students miss school; the loss in productivity when mom or dad misses work to care for the sick child; the loss of profit to the parent’s employer.

His savvy has paid off; during Utah’s legislative session last year, he worked on four bills, including one that equips all schools with emergency inhalers for students with asthma. All four passed.

A couple of years ago, university colleagues noticed the breadth of Mendoza’s interests and recommended that he read a research paper about ozone, a serious problem caused by sunlight in the American West. Ozone dissipates at night but, the study found, Los Angeles is so lit up by artificial lights that the ozone wasn’t breaking down as expected.

“They baited me with that paper,” he said, and he soon joined the university’s Consortium for Dark Sky Studies. He since has become the consortium’s co-director and editor of the Journal of Dark Sky Studies.

Though he has mentored students and guest-lectured for years, he’ll teach his first class next fall, the capstone class for the school’s new minor in dark sky studies. Students will study the effects of the loss of dark skies on human health, the ecology and tourism and will learn how to frame policy proposals to enact change.

In addition to his academic pursuits, Mendoza sits on the board of numerous service organizations and has organized three Breathe Clean festivals (he couldn’t attend the 2019 event because he was at DePauw to address students).

He also is an avid athlete. He learned during grad school that, if he read a problem and then went out for a run or bike ride, he could devise solutions and internalize a lesson. In 2007, he cycled in 84 road, off-road, track and velodrome races in the United States and, in 2008, he landed a spot on a professional cycling team in Spain, riding as a support worker for the team leaders. “Dream fulfilled,” he said, but “my science is more what’s my calling.”

While in Florida, he joined a six-runner group that won the Ragnar race from Miami to Key West. Less eager to run in mountainous Utah, he turned to snowshoeing. In 2016, he won the 10K and marathon international division competitions in the U.S. National Snowshoe Championships. He also skis cross-country and participates in running-cycling duathlons.

You might wonder if he ever sleeps. “I actually sleep a solid seven to eight hours a night,” he said. “I used to not, and then I started to read a lot more of the background on the impact of lack of sleep and the incidence of Alzheimer’s, and I decided that I want to remember my name when I’m 80.”

(Dark skies photo courtesy of Paul Ricketts.)

DePauw Magazine

Spring 2020

Leaders the World Needs: Alum who attended college against odds guides youths to do same

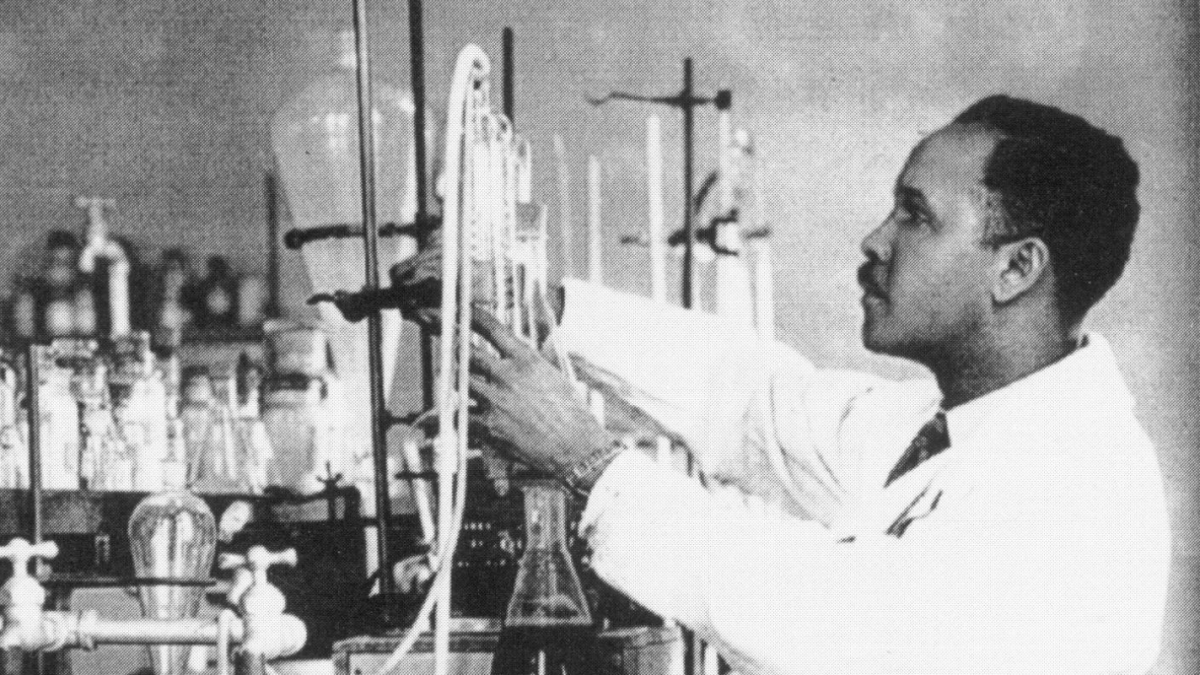

Leaders the World Needs: Alum who attended college against odds guides youths to do same OLD GOLD: Percy Julian, unappreciated in his time, inspires today

OLD GOLD: Percy Julian, unappreciated in his time, inspires today FIRST PERSON with Jonna McGinley Reilly '00

FIRST PERSON with Jonna McGinley Reilly '00  The Bo(u)lder Question By Rebecca Bordt

The Bo(u)lder Question By Rebecca Bordt The poet

The poet The iceman

The iceman The most American athlete ever

The most American athlete ever

The beekeeper

The beekeeper The juggler

The juggler The lucky guy

The lucky guy Aligned stars: Snowshoeing scientist studies the skies

Aligned stars: Snowshoeing scientist studies the skies Indelible images: Devastating photo, desperate need move alums to act

Indelible images: Devastating photo, desperate need move alums to act The nonconformists

The nonconformists A twist of fate: Unexpected discovery rekindles family legacy

A twist of fate: Unexpected discovery rekindles family legacy

DePauw Stories

A GATHERING PLACE FOR STORYTELLING ABOUT DEPAUW UNIVERSITY

Browse other stories

-

Athletics

-

Women's Swimming & Diving - DePauw Sets Two New Pool Records Against #11 WashU

-

Men's Swimming & Diving - Tigers Finish 102-204 Against #12 WashU in Dual-Meet

-

Men's Track & Field - Tigers Finish Fourth at Rose-Hulman Classic

More Athletics

-

-

News

-

DePauw University Remembers Esteemed President Emeritus Robert G. Bottoms

-

Student and Professor Share Unexpected Writing Journey

-

Four in a Row! DePauw Wins 131st Monon Bell Classic

More News

-

-

People & Profiles

-

Entrepreneurs Eric Fruth ’02 and Matt DeLeon ’02 Are Running More Than a Business

-

Rick Provine Leaves Legacy of Leadership and Creativity

-

History Graduate Cecilia Slane Featured in AHA's Perspectives on History

More People & Profiles

-

-

Have a story idea?

Whether we are writing about the intellectual challenge of our classrooms, a campus life that builds leadership, incredible faculty achievements or the seemingly endless stories of alumni success, we think DePauw has some fun stories to tell.

-

Communications & Marketing

101 E. Seminary St.

Greencastle, IN, 46135-0037

communicate@depauw.eduNews and Media

-

News media: For help with a story, contact:

Bob Weaver, Senior Director of Communications.

bobweaver@depauw.edu.