Leaders the World Needs

is a regular feature of DePauw Magazine, which is published three times a year.

“For me and for people who stay in public service a long time and enjoy it as much as I do,” said Shatrese Flowers ’95, “you have to really like people.”

That is some statement from someone who for more than 20 years has defended criminals, assisted judges on major cases and, for the past six years, served as a Marion County, Indiana, superior court judge, presiding over trials of people charged with homicide, major felony drug and gun offenses, child molestation and other heinous crimes. And whose courtroom once broke out in a melee when the defendant’s family didn’t like the guilty verdict.

(“I was upset then; I was heated,” she allowed. “I was frustrated and I think the record reflected that.”)

So there are exceptions, but for the most part, “you have to like different types of people,” she said. “Because the people you deal with in public service aren’t all like you or like your friends. They’re not all like your family. I mean, it’s a mix of everyone and everybody, different levels of education. Different social economic statuses. Different ethnicities. Different languages they speak.”

She wanted to be a lawyer since she was in fifth grade. Corporate law; definitely not criminal. But things change and people grow, and Flowers was drawn to criminal defense work while working at a small family-owned practice, her first job as a lawyer.

“I would cover cases for the father in criminal court and I thought, well, that’s kind of interesting. It’s more interesting than I thought.” She went to work as a public defender, intending to serve a year but staying three and a half.

She left when a spot came open in the Indianapolis corporation counsel office – the lawyers who represent city-county agencies and departments. Within 14 months, however, a more tempting opportunity opened: a spot as a superior court master commissioner, who works for elected judges. Flowers got the job and, over nine and a half years, progressed from working in the arrestee processing center to handling initial hearings for misdemeanors and low-level felonies to working for five to seven judges in a week.

“It taught me a lot, like looking at how different judges ran their courtrooms, how they interacted with staff,” she said. After a few years, lawyers began asking when she’d run for judge. “I don’t know,” she’d say. “I guess the time will be right.” In 2013, “I started thinking, I think now is the time … for me to be one of the decision-makers as far as having my own court.”

She won a six-year term, one of five new judges elected. Seniority rules the process: When judges retire, others move up to the coveted courts according to seniority, leaving the less desirable courts for the new judges to divvy up. Flowers’s time as a master commissioner counted, and, as the most senior among the newbies, she had first choice.

Her campaign manager suggested she choose traffic court; it would be easy. But after presiding over jury trials in lower-level felony court, “… I kind of wanted a challenge.”

She chose the major felony drug and gun court, which was rumored to be the busiest court in the state. The caseload was so voluminous that, two years later, it was split into two courts. When vacancies occurred in 2018, Flowers was able to choose again, and she picked a general major felony court, where she would see somewhat less mayhem.

She has learned a lot over 20 years, she said, including from the mother of a murder victim whose death was so violent that the crime scene photos haunted the judge.

“She wasn’t angry or bitter; she was forgiving,” Flowers said. “She was a woman of strong faith and her resolve and her demeanor just were something that resonated with me. … I thought, if she can be just so forgiving, I should be forgiving of anything and everything.”

Still, Flowers sentenced the defendant to more than 100 years. “Even though the act might be egregious and it’s warranted, it doesn’t feel good,” she said. “It doesn’t. But you know, I apply the law. I apply mitigating circumstances and aggravating circumstances in crafting the sentence. And I pronounce it.”

DePauw Magazine

Fall 2020

First Person: DePauw Nursing

First Person: DePauw Nursing Old Gold: The president and the benefactor: Close friendship created an enduring legacy

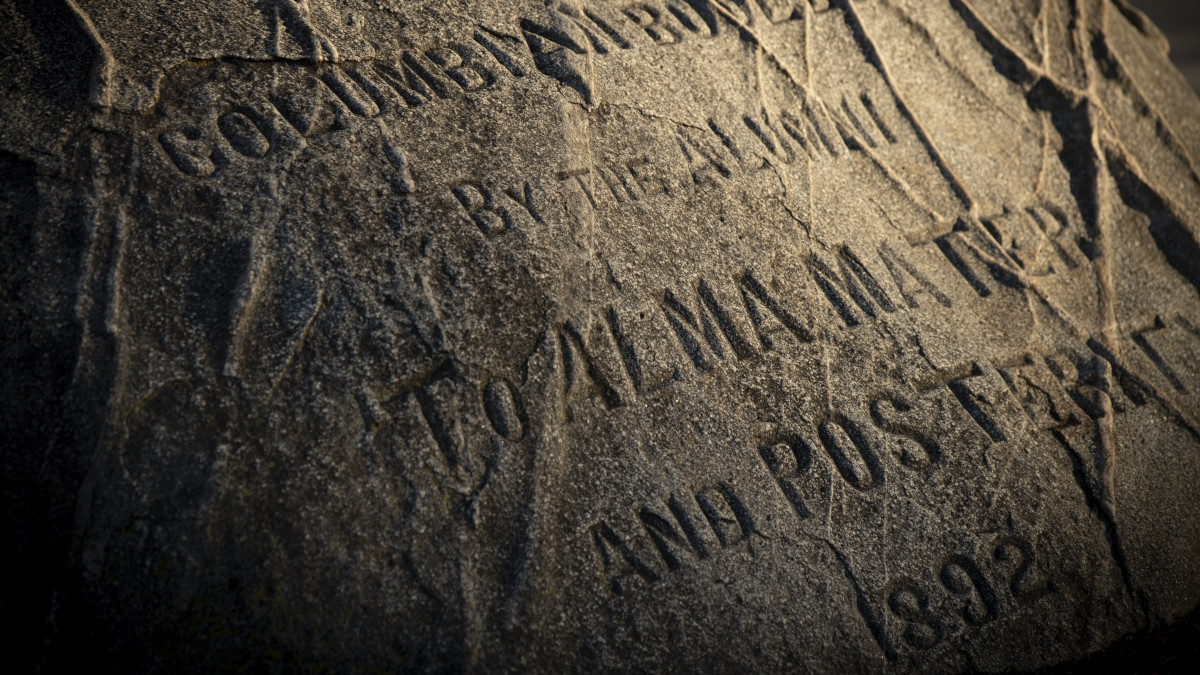

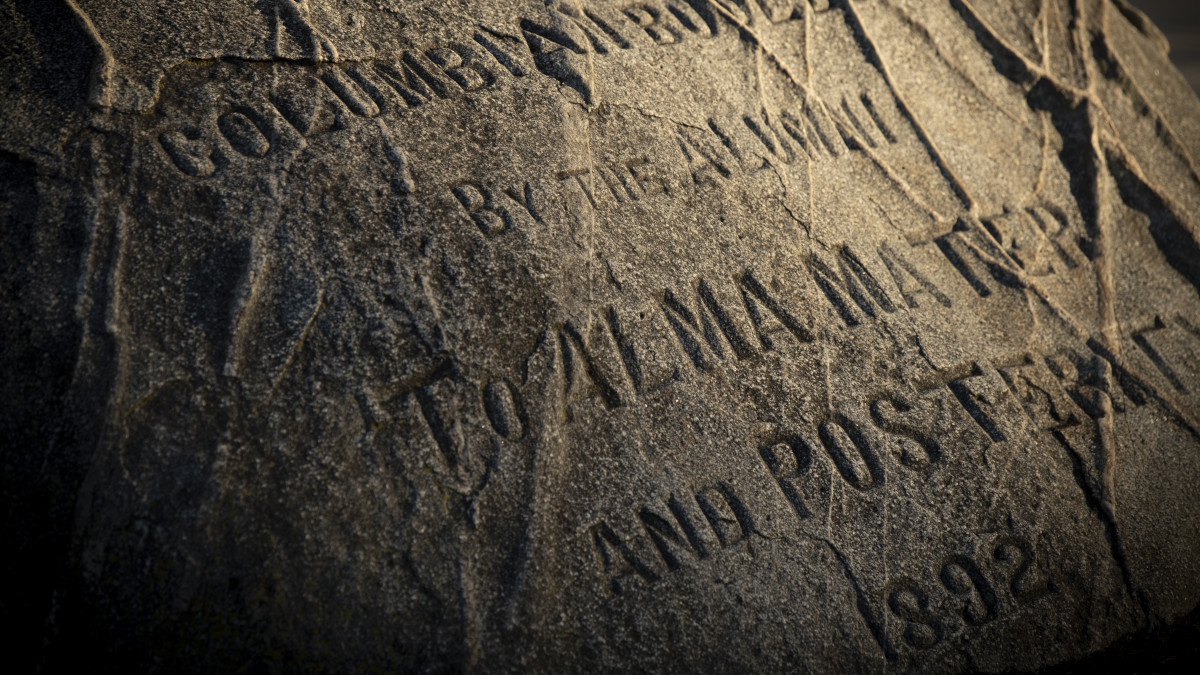

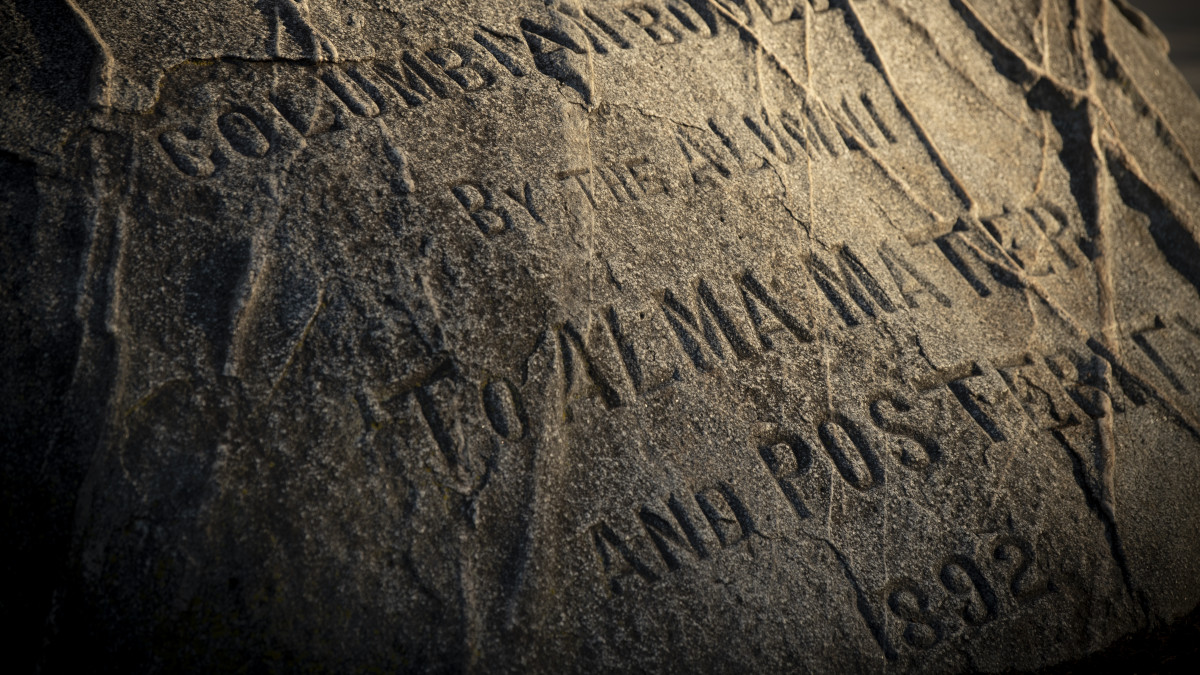

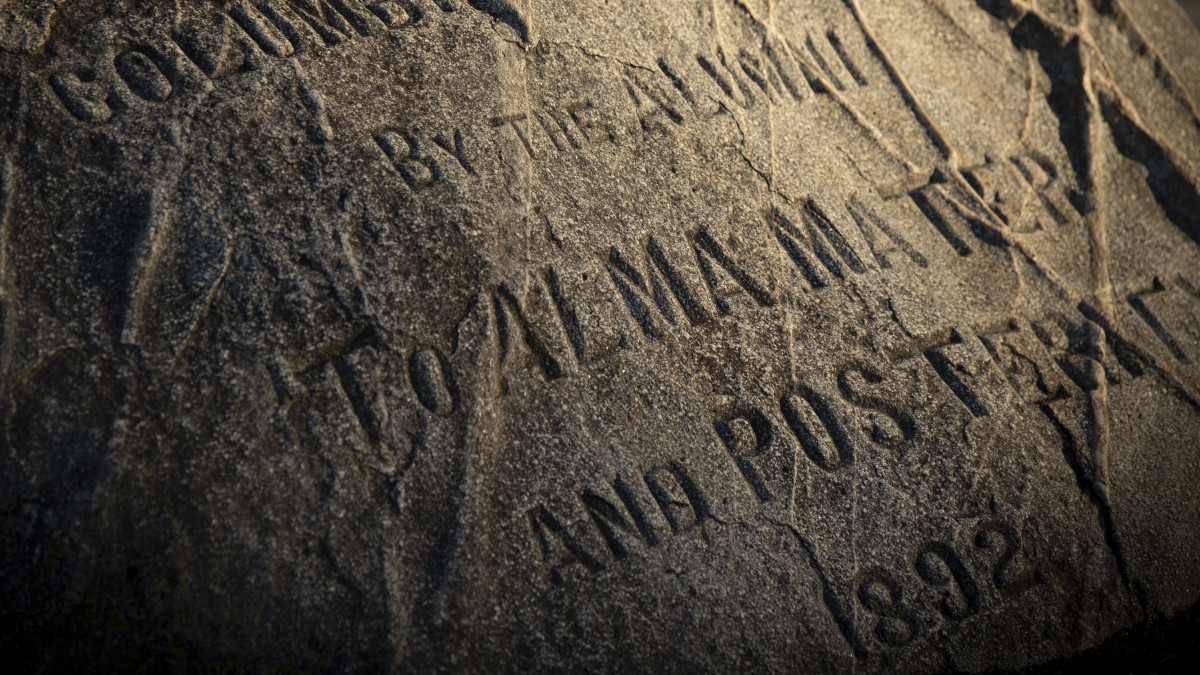

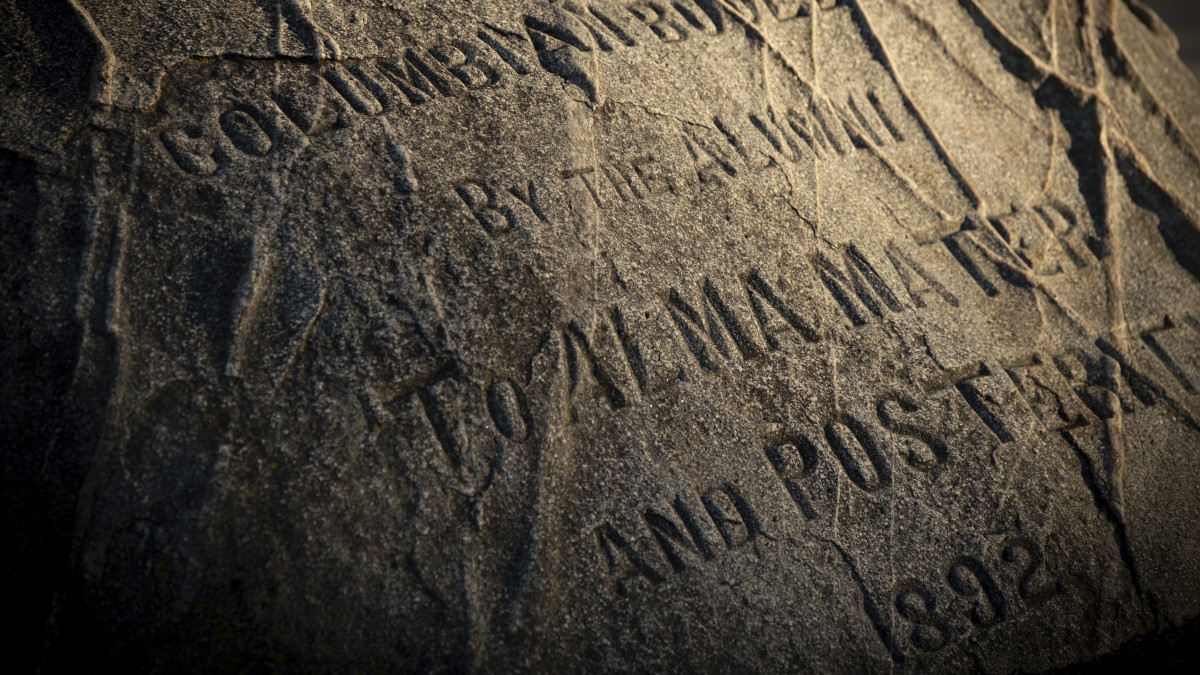

Old Gold: The president and the benefactor: Close friendship created an enduring legacy THE BO(U)LDER QUESTION: Racial Justice

THE BO(U)LDER QUESTION: Racial Justice THE BO(U)LDER QUESTION: Racial Justice

THE BO(U)LDER QUESTION: Racial Justice THE BO(U)LDER QUESTION: Racial Justice

THE BO(U)LDER QUESTION: Racial Justice THE BO(U)LDER QUESTION: Racial justice

THE BO(U)LDER QUESTION: Racial justice THE BO(U)LDER QUESTION: Racial Justice

THE BO(U)LDER QUESTION: Racial Justice THE BO(U)LDER QUESTION: Racial Justice

THE BO(U)LDER QUESTION: Racial Justice THE BO(U)LDER QUESTION: Racial Justice

THE BO(U)LDER QUESTION: Racial Justice THE BO(U)LDER QUESTION: Racial Justice

THE BO(U)LDER QUESTION: Racial Justice THE BO(U)LDER QUESTION: Racial Justice

THE BO(U)LDER QUESTION: Racial Justice THE BO(U)LDER QUESTION: Racial Justice

THE BO(U)LDER QUESTION: Racial Justice The Bo(u)lder Question: Racial Justice

The Bo(u)lder Question: Racial Justice The Bo(u)lder Question

The Bo(u)lder Question The Bo(u)lder Question: Racial Justice

The Bo(u)lder Question: Racial Justice THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: Jane Noble Luljak ’49

THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: Jane Noble Luljak ’49 THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: Veronica Pejril

THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: Veronica Pejril THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: Terry Crone ’74

THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: Terry Crone ’74 THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: John Hammond ’76

THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: John Hammond ’76 THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: Dave Jones ’84

THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: Dave Jones ’84 THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: Lucy Ferguson VanMeter ’97

THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: Lucy Ferguson VanMeter ’97 THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: J.P. Hanlon ’92

THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: J.P. Hanlon ’92 THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: Brittany Bulleit ’05

THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: Brittany Bulleit ’05 THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: Sue Anne Starnes Gilroy ’70

THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: Sue Anne Starnes Gilroy ’70 THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: Dan Quayle ’69

THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: Dan Quayle ’69 THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: Shatrese Flowers ’95

THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: Shatrese Flowers ’95 THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: C. Shea Nickell ’81

THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: C. Shea Nickell ’81 The Public Servants: Nancy Boyer ’73

The Public Servants: Nancy Boyer ’73 THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: Matthew Kincaid ’92

THE PUBLIC SERVANTS: Matthew Kincaid ’92 The Public Servants

The Public Servants Profs see promise in poli sci, history students who plan public service careers

Profs see promise in poli sci, history students who plan public service careers Stimulated and prepared by DePauw, alums work to serve others

Stimulated and prepared by DePauw, alums work to serve others

DePauw Stories

A GATHERING PLACE FOR STORYTELLING ABOUT DEPAUW UNIVERSITY

Browse other stories

-

Athletics

-

Women's Swimming & Diving - DePauw Women Recognized as a Spring 2025 Scholar All-America Team; Three Tigers Recognized

-

Men's Swimming & Diving - DePauw Men Recognized as a Spring 2025 Scholar All-America Team

-

Men's Basketball - Tigers Earn NABC Team Academic Excellence Award; Four Student-Athletes Named to Honor Court

More Athletics

-

-

News

-

National grant supports DePauw’s commitment to civil dialogue

-

Outstanding scholars named to Spring 2025 Dean's List

-

Alumni News Roundup - June 6, 2025

More News

-

-

People & Profiles

-

11 alums make list of influential Hoosiers

-

DePauw welcomes Dr. Manal Shalaby as Fulbright Scholar-in-Residence

-

DePauw Names New Vice President for Communications and Strategy and Chief of Staff

More People & Profiles

-

-

Have a story idea?

Whether we are writing about the intellectual challenge of our classrooms, a campus life that builds leadership, incredible faculty achievements or the seemingly endless stories of alumni success, we think DePauw has some fun stories to tell.

-

Communications & Marketing

101 E. Seminary St.

Greencastle, IN, 46135-0037

communicate@depauw.eduNews and Media

-

News media: For help with a story, contact:

Bob Weaver, Senior Director of Communications.

bobweaver@depauw.edu.