Cartography in the Age of Google

November 23, 2010

The first time you step into Beth Wilkerson’s GIS Center, you know you’ve found the right place. Except for her desk, a large-format printer and scanner, the room is covered with maps she’s helped to conceive. There are images from an animated map that shows the waxing and waning of Chinese dynasties, and archaeological maps created for the Collaboratory for GIS and Mediterranean Archaeology (CGMA), the project that brought Wilkerson to DePauw in 2002. Judging by her walls, most of the University’s academic departments have passed through her office at one time or another.

“I went into computer science because it was applicable to every discipline,” Wilkerson says. “I enjoy GIS for the same reason. It gives me a chance to learn about things like public policy or archaeology while I’m providing the technical expertise to spatially visualize and analyze data for projects in these fields.”

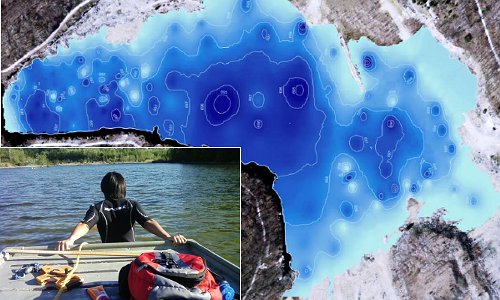

Every fall for GIS Day, part of the National Geographic Society’s Geography Awareness Week, Wilkerson displays the most recent GIS projects from students and faculty members. This year’s event featured everything from how glaciers created Indiana’s farmland, to the effects of deforestation in Brazil and Zambia. Alan K.W. Lee ’12 and Neil T. Fitzharris ’10 channeled their inner Lewis and Clark to create a map of the DePauw Nature Park quarry pond. Wearing a wetsuit he had from a trip to the Galapagos Islands, Lee held Fitzharris in place in a small boat as he took depth and GPS readings, which Wilkerson helped them turn into a three-dimensional model of the pond floor.

“I consider Beth to be the single most important support person on campus,” says Kelsey Kauffman, assistant professor of University studies. “She makes DePauw a really special place.”

That’s high praise, and for good reason. Just as they did in Columbus' time, maps play a significant role in how we understand the world around us. Wilkerson is one of a new breed of cartographers using computer-based GIS, or geographic information systems, to create powerful visual tools. Her maps are truly living things, impacting the lives of people far beyond DePauw's campus – even if they don't know it.

Three years ago, Kauffman’s 2007 Winter Term class was packed into a crowded Senate committee hearing at the Indiana Statehouse. Most of the people who filled the gallery that day were there to discuss a highly publicized bill regulating cell phone use. But that was the second item on the agenda.

Before the committee could move on to the main event that had attracted reporters and industry lobbyists, Kauffman’s students were scheduled to testify on Senate Bill 3, a proposed expansion of Indiana’s anti-drug laws.

Since the 1970s, states have designated places such as schools and public parks as drug-free zones. The zones carry a harsher penalty for being caught with narcotics near a playground than on the interstate. Senate Bill 3 simply added places of worship to the list of existing drug-free zones. And who would vote against that?

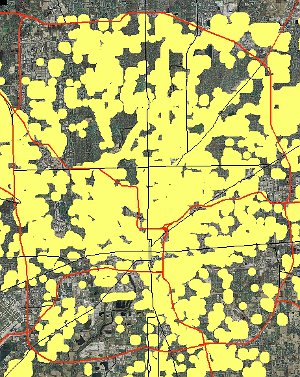

As good as the bill’s intentions were, there were significant consequences – you just needed a bird’s-eye view to see them. Kauffman’s students brought maps that Wilkerson had helped them create, showing how including churches as drug-free zones would affect Marion County and the city of Indianapolis. By adding the city’s churches to its parks and schools – with a 1,000-foot buffer surrounding each – few places in Indianapolis wouldn’t be covered by drug-free zones.

As good as the bill’s intentions were, there were significant consequences – you just needed a bird’s-eye view to see them. Kauffman’s students brought maps that Wilkerson had helped them create, showing how including churches as drug-free zones would affect Marion County and the city of Indianapolis. By adding the city’s churches to its parks and schools – with a 1,000-foot buffer surrounding each – few places in Indianapolis wouldn’t be covered by drug-free zones.

(Right: A map of drug-free zones, in yellow, in Indianapolis as a result of the proposed expansion.)

The law that was meant to push drug activity away from children would, in effect, become redundant. Drug dealers would either move into the communities surrounding the city, or simply target schools and parks because there would no longer be an added disincentive to avoid them.

“The reason why the zones are considered important is that they make a school or a park a special place,” Kauffman says. “I don’t want drug dealers near churches. I also don’t want them near Chuck E. Cheese’s. But once you blanket the entire city with drug-free zones, as this bill would have done, you’ve lost the special protection.”

Four students – then-freshmen Keelin A. Kelly, Curtis G. Moore, Rebecca M. Murphy and Megan Tucker-Hall – took turns presenting their maps. The six minutes that had been allotted for their testimony turned into almost two hours of increasingly contentious questioning. Exchanges between the senators became especially heated.

“At one point, the chair of the committee told two legislators to go outside if things were going to come to blows,” says Kelly, who now works in energy policy for the Colorado Public Interest Research Group.

When it came time for a vote to move the bill out of committee, the senators were deadlocked. Another committee member, who hadn’t been present during the group’s testimony, had to be called into the room to cast the deciding vote in its favor. But the students’ testimonies had irreversibly changed the bill’s course. Senate Bill 3 – once a political winner, absolutely sure to become law and propel its sponsors to reelection – was defeated in a Senate vote.

As a measure of their success, lobbyists even approached Kauffman after the hearing, offering to hire students from her class. It was a triumph of representative democracy, but Kauffman and Kelly confess they had a secret weapon in the maps.

“Our maps were so great because they were clear and factual,” Kelly says. “The legislators couldn’t ignore the information we presented, and some of them later used our maps on the Senate floor to defeat the bill.”

“There’s no way anybody could have understood the impact of the bill without the maps,” agrees Kauffman. “We went to Beth to ask for her help, and she immediately said, ‘I can tell where all the churches are.’ She goes to a data set that none of us know exists. You and I could not in our wildest dreams create these maps by ourselves. It’s Beth that made them work.”