So you want to write a novel. Be prepared for intense preparation, exhaustive research, careful writing and meticulous revision.

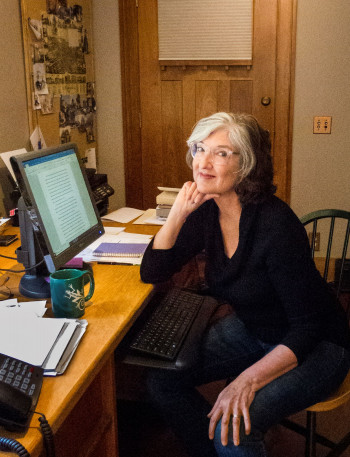

That’s what you can expect, anyway, if you follow the lead of Barbara Kingsolver ’77, bestselling author of eight novels and eight other books. Though engrossed in work on a new one, she responded in writing to DePauw Magazine’s questions about how to write a bestseller.

The plot thickens:

PROLOGUE: “I get ideas everywhere,” she said. “On a walk in the woods, in the grocery. I’m a chronic eavesdropper. I love listening to people’s language, their points of view. …

“Nothing ‘just comes.’ I spend years evaluating ideas for their literary potential. For a novel to be worth a reader’s time (and mine), it needs to be about something extremely and universally important, so I lean into my biggest worries. Some examples from my past novels: climate change, partisan divides between rural and urban people, cultural paradigm shifts, the history of colonial arrogance, child abuse. … The hard part is finding a way into a story that will ask big questions, guiding a reader through a compelling exploration of the subject.”

Early in a book project, Kingsolver spends time “choosing and honing a subject, sketching the architecture of the plot, inventing the characters and finding the story’s voice. I usually spend a year or more on those things before I write the first sentence, the first scene, so I’m very clear about where it’s all going.”

THE SETTING: Kingsolver works on a desktop computer in a book-lined, upstairs office in her family’s Virginia farmhouse. It’s quiet; “any kind of music or noise is distracting, because I’m listening to voices in my head,” she said.

“Does that sound, um, crazy? To be honest, fiction writing might be a carefully controlled lunacy.”

A map of her novel’s location – real or drawn by her – hangs on a nearby bulletin board, surrounded by photos “that resemble important images in my mind – my characters (faces or body types), crucial possessions, articles of clothing, views out a window. It grows into a giant collage. If my novel has an exotic location that’s far from the real view out my real window – like the Congo, Mexico or the 19th century – these visual cues help to get me centered in the world of my novel. I’ll often begin my writing day standing in front of that bulletin board, letting my focus go soft and walking in. Like Alice’s looking glass.”

A map of her novel’s location – real or drawn by her – hangs on a nearby bulletin board, surrounded by photos “that resemble important images in my mind – my characters (faces or body types), crucial possessions, articles of clothing, views out a window. It grows into a giant collage. If my novel has an exotic location that’s far from the real view out my real window – like the Congo, Mexico or the 19th century – these visual cues help to get me centered in the world of my novel. I’ll often begin my writing day standing in front of that bulletin board, letting my focus go soft and walking in. Like Alice’s looking glass.”

She begins by creating computer files to store descriptions of her characters and their histories; timelines; themes; and “a big, expanding plot outline.” When she has worked out the plot, she creates a file for each chapter, starting with a few sentences about what will happen in it. “As the story develops and I know more, I can fill these out in greater length,” she said. “By the time I actually begin writing the novel scene by scene, I never start with a blank page. …

“Once I’m well into the book, I’ll jump around a lot. Ideas come to me for scenes that happen at various points mid-novel, and I can write them and put them in place. At some point, usually pretty early on, I’ll get a clear vision of the book’s final scene, and write it. The end is always written long before I reach that point in the first draft. That way, I can aim everything else toward that focal point, making sure it all adds up just right.”

"Close the door. Write with nobody looking over your shoulder. Don't try to figure out what other people want to hear from you. Figure out what it is you have to say."– Barbara Kingsolver

THE INITIATING EVENT: Kingsolver majored in zoology at DePauw (the precursor to biology), figuring it would lead to a “secure livelihood.” Writing, she said, “was a private passion that grew out of my love of reading. Novels opened the windows of my brain. I started keeping a journal at age 8, and never stopped. I had no ambition to become a professional writer … I just wrote every day, as a way of processing my experience.”

By college age, “I was reading very consciously, noticing how Dickens constructed his plots, how Steinbeck used point of view to reveal character. Doris Lessing blew my mind, showing me that a novel is – or can be – not just about plot and character but also the biggest problems in the world, like sexism and racism.”

RISING ACTION: “I’m always creating on the page, even if I’m working within a planned plot,” Kingsolver said. “The creation is craft. Choosing the exquisitely right words, making sentences that sing, finding the poetry of language.”

She is not influenced by public acclaim or reader expectation, she said. “You don’t get a backlist like mine by trying to please an audience. I mean, let’s face it: climate change, racism, death by snakebite – these things do not scream ‘marketable.’ I just concentrate on doing my best work, even if it takes me into dark and scary places, and trust readers to follow me.

“Many years ago I wrote these words of advice that are now popping up every day in my Instagram feed, so they must be ringing true: ‘Close the door. Write with nobody looking over your shoulder. Don’t try to figure out what other people want to hear from you. Figure out what it is you have to say. It’s the one and only thing you have to offer.’”

CONFLICT: When she embarks on a new book, even after writing 16, “I struggle all over again with the sense that this is too hard, I’ve bitten off more than I can chew, I won’t be able to pull it off,” she said. “When I start feeling daunted, I have to take a deep breath and give myself permission to write a bad first draft. … That permission is very liberating.”

Some of her best thinking occurs in bed, “when I’m first awake in a dreamy state. Often, when I have a tough writing knot to untangle, I’ll set the specific intention of knowing the answer the next morning. And usually, I do.” Other times, she’ll take a five-minute walk, using “basically the same techniques that are helpful in amicably settling disputes with a spouse.

“In some ways, writing a novel is like a marriage. You have to keep showing up, enjoying the company and, when problems arise, you trust the process of working them out.”

CLIMAX: “For me, the real art is in revision,” Kingsolver said. “It’s most of the work I do. Honing the language, finding new insights into character, rearranging scenes and events to build the story more perfectly. … I promise you, every paragraph of mine is rewritten at least a dozen times before it’s published. Some are rewritten a hundred times. The first page, probably two hundred.”

FALLING ACTION: The time it takes for Kingsolver to complete a novel varies. Some were written in two years; “The Lacuna” took about seven; “The Poisonwood Bible,” 20. “I also worked on other things during that time, but I was actively writing that novel for two decades,” she said.

DENOUEMENT: When a book is finished, “it’s a cathartic ritual to take down all those pictures and start again with a clean cork surface, waiting to be filled,” she said. In between books, she works on smaller projects – travel articles, magazine pieces, essays.

“It’s therapeutic, looking forward to these projects as small treats, because finishing a book is strangely sad,” she said. “There’s a postpartum letdown, the painful farewell to these people who’ve been living in my head for several years.”

She has no plans to retire. Writers “tend to hit our stride in middle age and could actually do our best work in our 70s or 80s,” she said, “because our stock in trade is not just language, it’s wisdom. Isn’t that what readers are really looking for? And wisdom can’t be rushed; it only accrues with time and experience.”

DePauw Magazine

Spring 2021

Leaders the World Needs

Leaders the World Needs First Person by Nate Spangle ’19

First Person by Nate Spangle ’19  The Bo(u)lder Question

The Bo(u)lder Question  How to reckon with the past

How to reckon with the past How to die peacefully

How to die peacefully How to be creative in a crisis

How to be creative in a crisis How to do well by doing good

How to do well by doing good How to argue before the Supreme Court

How to argue before the Supreme Court How to run for your life

How to run for your life How to write a love letter

How to write a love letter How to create art

How to create art How to find Jimmy Hoffa

How to find Jimmy Hoffa How to break into TV

How to break into TV How to be happy

How to be happy  DePauw Magazine: The How-To Issue

DePauw Magazine: The How-To Issue Town-gown: How to find common ground on common ground

Town-gown: How to find common ground on common ground How to write a bestseller

How to write a bestseller How to save a life

How to save a life

DePauw Stories

A GATHERING PLACE FOR STORYTELLING ABOUT DEPAUW UNIVERSITY

Browse other stories

-

Athletics

-

Women's Golf - Williams Selected Academic All-America®

-

Football - 336 Students Named to 2025 Spring Tiger Pride Honor Roll

-

Football - DePauw-Record 190 Student-Athletes Named to NCAC's Dr. Gordon Collins Scholar-Athlete Honor Roll

More Athletics

-

-

News

-

Outstanding scholars named to Spring 2025 Dean's List

-

Alumni News Roundup - June 6, 2025

-

Transition and Transformation: Inside the First-Year Experience

More News

-

-

People & Profiles

-

11 alums make list of influential Hoosiers

-

DePauw welcomes Dr. Manal Shalaby as Fulbright Scholar-in-Residence

-

DePauw Names New Vice President for Communications and Strategy and Chief of Staff

More People & Profiles

-

-

Have a story idea?

Whether we are writing about the intellectual challenge of our classrooms, a campus life that builds leadership, incredible faculty achievements or the seemingly endless stories of alumni success, we think DePauw has some fun stories to tell.

-

Communications & Marketing

101 E. Seminary St.

Greencastle, IN, 46135-0037

communicate@depauw.eduNews and Media

-

News media: For help with a story, contact:

Bob Weaver, Senior Director of Communications.

bobweaver@depauw.edu.