A narrow blue line threads out from beneath Ben Solomon’s sleeve and another from the V formed by his crumpled shirt collar.

Tattoos. He’s up to three now, inked onto his skin “whenever I find a story or a person I’m dealing with that makes me feel like I should mark the moment, I guess. Or just remember it in some sense,” says Solomon, a 2010 DePauw graduate and a video journalist for the New York Times.

“My mother would be happy if I did something else.”

He tells bits of his story as he points to each tattoo successively, but does not move the shirt to reveal the evidence that his work has literally marked him permanently. Too revealing? Too painful?

One tattoo recalls Iraq, where Solomon was embedded with Iraqi troops fighting the Islamic State group in Falluja. Another commemorates his visit to a hillside refugee camp in Bangladesh, where Rohingya Muslim refugees – having escaped rapes, killings and the incineration of their houses by the military in their home country of Myanmar – face mudslides and disease.

The clouds on his right bicep were inspired by the “burial boys” he covered during the Ebola crisis in West Africa, young men who volunteered or, if they were lucky, were paid a pittance to pick up the bloodied and infectious bodies of victims.

Mohammad Shafi

Mohammad Shafi

Solomon accompanied two burial boys to a remote village, where they interred a suspected victim according to a strict protocol. A rainstorm broke as they drove back on an increasingly muddy road, necessitating unnerving speed in the pitch-black jungle to avoid getting stuck. The burial boys, unfazed by their grisly task, were equally unfazed by the circumstances, and one struck up a conversation, inquiring where a shaky Solomon lived.

“I don’t really live anywhere,” Solomon recalls saying. “I just kind of float around, just kind of bounce here to there – just floating about. He said, ‘oh, so you’re a cloud man.’ I’m like, I guess I am. And he said, ‘Don’t worry; you’ll find a cloud woman one day.’ It was so sweet. So I got clouds tattooed on me.”

Solomon has another reminder of his experiences covering the epidemic that killed more than 10,000 people in West Africa: the memento in his mother’s curio cabinet that signifies his membership in the six-journalist Times team that won the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for international reporting.

It is not lost on Solomon, 31, that he was remarkably young – 27 – when he won journalism’s highest honor. “An editor once told me you should never win a Pulitzer Prize before you’re 30 because it’ll ruin your life. I’m trying not to make that true, because in truth a lot of journalists work their whole life to achieve such high journalism that they can be proud of and I have fallen into so many lucky situations.”

Fallen? Maybe. But Solomon frequently makes his own luck, including his experiences with DePauw. He came to Greencastle with one goal – to play football. He had played in high school in St. Louis, offensive lineman and defensive tackle, and longed to do the same in college. DePauw gave him the opportunity.

An editor once told me you should never win a Pulitzer Prize before you’re 30 because it’ll ruin your life. I’m trying not to make that true ...– Ben Solomon ’10

In choosing DePauw, he had rejected the expectation of his parents, both journalists, who figured he’d go to the University of Missouri, a journalism-education powerhouse. Instead, Solomon chose to participate in DePauw’s Media Fellows Program, though he planned a career in film making. Traditional journalism, he believed, was confining and “lame … I didn’t like the idea of working for one place for a long amount of time and climbing slowly up the ladder.”

As for football, “I was a punching bag; I was terrible,” he says. He was intent on transferring when his adviser, communication and theatre professor Jonathan Nichols-Pethick – who had observed that Solomon seemed aimless and who acknowledges he was frustrated by Solomon’s nonchalance about requirements – quizzed him on what he wanted from DePauw.

“I said, I want to go abroad,” Solomon recalls. “I want to go back to Israel,” where he had visited for a Birthright trip when he was 18. “I like it there. I want to see what I can do there. He was, like, cool. They didn’t have a program there and there were a lot of big safety issues. … He was really good about helping me organize around those and going through the college and getting credit for it, even though it wasn’t at all in their standardized list of places.”

Solomon studied at Tel Aviv University in the first semester of his junior year. A friend of his mother, who is a journalism professor at Webster University in St. Louis, helped him land an internship at CBS Evening News with Katie Couric in New York for the second semester.

“Junior year was so important to my development and then my senior year I came back (to DePauw) and I was like, why was I so pretentious?” he recalls. “This place is amazing. I have all my friends here; I live in a good house. It’s so nice. By the end of it, I was really kind of kicking myself for ever even doubting that I liked it there.”

Finally, says Nichols-Pethick, Solomon “seemed to be intellectually a lot more curious and engaged.”

Determined too. While working at CBS – an experience he found “restricting” – Solomon took a class in improvisation, where a classmate was a video producer for the New York Times. He suggested she give him an internship; she blew him off.

“But then over the year I just kept pestering her – calling her when I was back at DePauw. By the end of the year I kept in touch with her, I kept emailing her. She was like, ‘OK, I’ll forward your info to the internship people; we’ll see what they say.’” As an exotic Midwesterner, he stood out from the pack of East Coast applicants and was invited to New York for an interview, where he was told the summer internship was unpaid and thus required him to earn college credit. Only problem was, Solomon had all the credits he needed to graduate in May. He nevertheless assured the interviewers that he would get credit for the internship.

An offer set Solomon scrambling. He told his advisers at the Pulliam Center for Contemporary Media that “I need something that says I’m getting school credit. …They were like, we got it.”

Nichols-Pethick, now director of the Pulliam Center and the Media Fellows Program, acknowledges that he and the director at the time skirted the rules. “The last thing I want to do,” he says, “is stand in the way of an opportunity for somebody because it doesn’t meet an exact criterion.”

During the internship, Solomon made video stories and volunteered to do a project in which no one else had interest. This kind of journalism, he thought, was neither limiting nor lame.

“It wasn’t really until I got here at the Times that I started realizing that that wasn’t how it had to be,” he says. “By the time I got out of college, I realized that you can mix that ambition to make things that feel different, feel special and feel captivating and artistic – you can mix that with journalism and still make it powerful.”

On the last day of his internship, a Friday, the Times staff feted Solomon and other interns. “Monday came around and I just didn’t really know what to do; I had nothing planned so I just figured I’d go back into the office,” he says. “I went to my desk, which was still empty, and I sat down and my editor walked up and he was, like, ‘well, I thought we kicked you out of here; I thought we said goodbye.’ (I said) ‘Yeah, you know, I’m just organizing files and finishing up this project, this little thing. I just wanted to make sure it’s OK.’ He was, like, ‘oh, OK. Well, do you want to shoot? We have this thing; we need another shooter. Can you help? Can you help shoot?’ I was, like, yeah. He was, like, ‘oh, OK, I guess we have to pay you now.’ And that’s how my freelance career began there.”

After a couple of months, the Times offered Solomon a contract. Then in December, when the Arab Spring broke out, Solomon begged his editors to let him cover the revolutions. No. Eventually, they agreed he should travel with columnist Nicholas Kristof to interview refugees displaced by the uprisings but, most decidedly, not be near the violence. A “crazy string of events” kept Kristof from meeting up with Solomon just as rebel troops were advancing on the capital of Libya, Tripoli. Solomon cajoled and his editors capitulated, sending him with veteran reporter Anthony Shadid to cover the fighting there.

I realized that you can mix that ambition to make things that feel different, feel special and feel captivating and artistic – you can mix that with journalism and still make it powerful.– Ben Solomon ’10

His contract work led to a full-time position. During his eight years with the Times, he has covered stories in 51 countries. In June 2017 he was named the Times’s first-ever visual-first correspondent, stationed in the bureau in Bangkok and assigned Southeast Asia as his first beat.

Despite his constant travels, Solomon frequently talks with DePauw students in person or by Skype and promptly responds to their emails, Nichols-Pethick says. Madison Dudley ’18 says he inspired her to intern in Israel and to pursue an international reporting career. “Before I met him, my biggest idol was Richard Engel from NBC News,” she says. “Now it’s someone who went to DePauw who … has gone on to do these things. It felt like it was more of a real possibility.”

Solomon says helping younger people get started in journalism helps him cope with the horrors he has seen and the dangers to which he is regularly exposed. So does therapy.

Says Marilyn Culler, assistant director of the Media Fellows Program: “He has found a way to navigate the deep sorrows of the world and find joy in living.”

James Stewart ’73, a New York Times business columnist and Pulitzer winner, says of Solomon: “I don’t think he has the fear gene, or maybe it’s just very weak. So much so that, after he got back from covering Ebola, we had a conversation and I asked him to promise me he wouldn’t put himself at undue risk of physical harm. He did promise, but I don’t think that would ever stop him. That’s just his nature. Of course that’s also one of his great strengths as a reporter.”

It’s stuff that doesn’t just pass through you. This stuff sticks onto your person. I will remember these places and these people for as long as I’ll live.– Ben Solomon ’10

Solomon shakes off the suggestion that he is fearless, saying, “when I covered Ebola, it was really emotionally and mentally taxing. I’ve covered two wars now. I’ve covered the Rohingya crisis. It’s stuff that doesn’t just pass through you. This stuff sticks onto your person. I will remember these places and these people for as long as I’ll live…

“The way that I justify or the way that I make sense of it is through the lens, through the camera. Yeah, I see really hard and horrible things. I see stories that are some of the most desperate in the world. But the reality is that, as long as my camera is pointing on them, as long as I feel like I’m making stuff that is a contribution, that’s representative of these people, these tragedies and these challenges, as long as I’m justifying my being there with making something that’s important and meaningful to their stories and to these situations, then it feels like I can make sense of it emotionally.”

DePauw Magazine

Fall 2018

1,000 WORDS’ WORTH

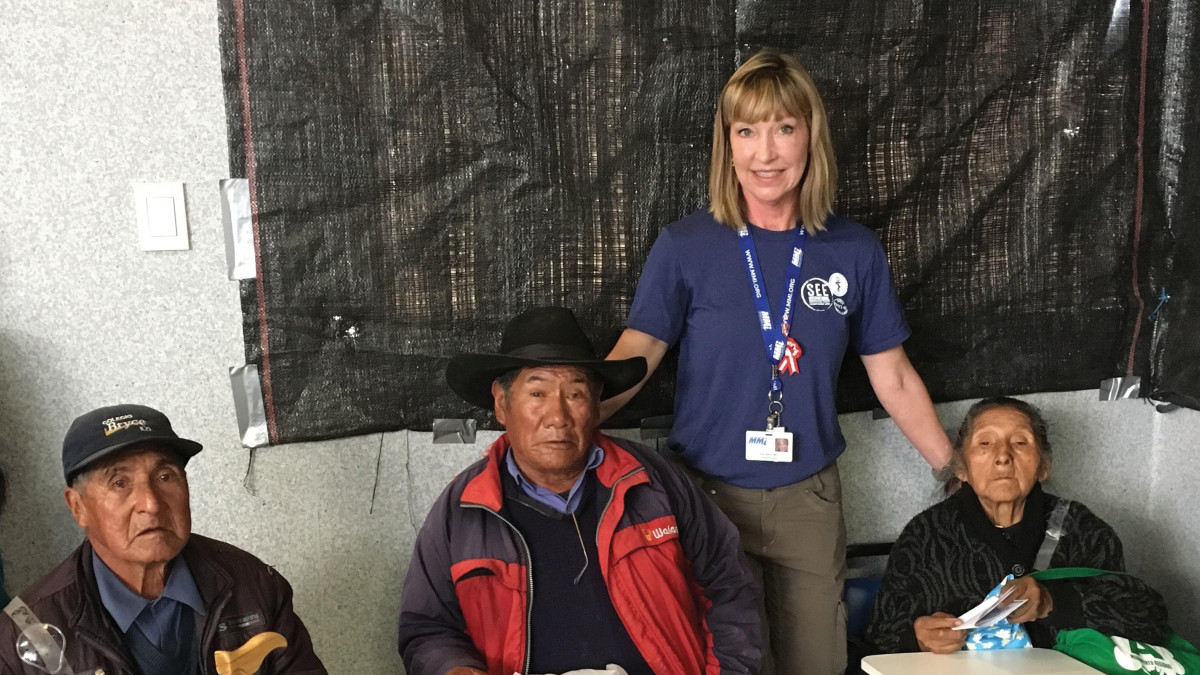

1,000 WORDS’ WORTH Gifted surgeon gives up lucrative practice to give sight to others

Gifted surgeon gives up lucrative practice to give sight to others First Person with Louis Smogor

First Person with Louis Smogor Practitioner or consumer?

Practitioner or consumer? The Storytellers

The Storytellers Hidden legacy: Genealogical search strengthens alum's bond to DePauw

Hidden legacy: Genealogical search strengthens alum's bond to DePauw The High-Flyin’ Class of ’92

The High-Flyin’ Class of ’92 This stuff sticks onto your person

This stuff sticks onto your person

DePauw Stories

A GATHERING PLACE FOR STORYTELLING ABOUT DEPAUW UNIVERSITY

Browse other stories

-

Athletics

-

Women's Golf - Williams Selected Academic All-America®

-

Football - DePauw-Record 190 Student-Athletes Named to NCAC's Dr. Gordon Collins Scholar-Athlete Honor Roll

-

Football - 336 Students Named to 2025 Spring Tiger Pride Honor Roll

More Athletics

-

-

News

-

Outstanding scholars named to Spring 2025 Dean's List

-

Alumni News Roundup - June 6, 2025

-

Transition and Transformation: Inside the First-Year Experience

More News

-

-

People & Profiles

-

11 alums make list of influential Hoosiers

-

DePauw welcomes Dr. Manal Shalaby as Fulbright Scholar-in-Residence

-

DePauw Names New Vice President for Communications and Strategy and Chief of Staff

More People & Profiles

-

-

Have a story idea?

Whether we are writing about the intellectual challenge of our classrooms, a campus life that builds leadership, incredible faculty achievements or the seemingly endless stories of alumni success, we think DePauw has some fun stories to tell.

-

Communications & Marketing

101 E. Seminary St.

Greencastle, IN, 46135-0037

communicate@depauw.eduNews and Media

-

News media: For help with a story, contact:

Bob Weaver, Senior Director of Communications.

bobweaver@depauw.edu.