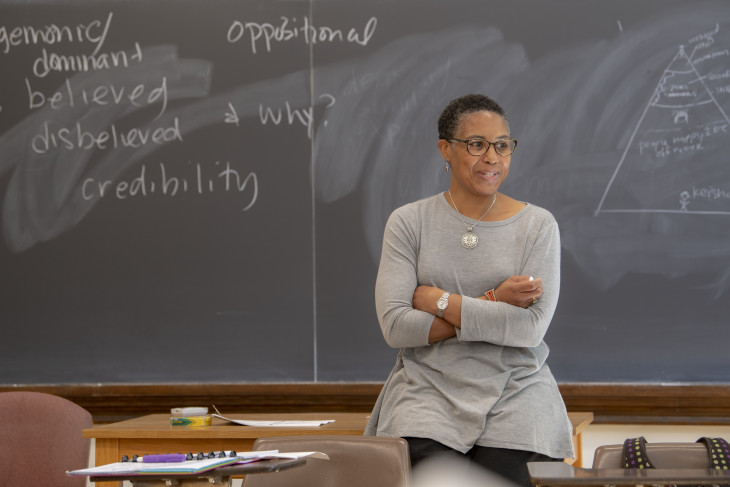

An intervention. That’s how Tamara Beauboeuf describes the first-year seminar she teaches.

Matthew Oware, meanwhile, wants his first-year seminar to complicate things.

What the heck is going on?

“Growing Up Girl” and “Man Up: Unpacking Manhood and Masculinity” are two of 33 semester-long seminars that introduce first-year students to their academic advisers, encourage them to think critically and enable them to sharpen their written and oral communication skills.

Beauboeuf, professor of women’s, gender and sexuality studies, says she pointedly developed “Growing Up Girl” as a first-year seminar to signal to its participants that “women belong here. Women have something of value here. And when I say ‘women,’ I don’t mean one kind of woman. I mean diverse women.”

Although women make up 52 percent of the student body, “this is not our campus,” she says. “Women don’t have half the power. The social scene, the structures of power among students, are not ones that favor women.”

Beauboeuf recalls “a very disturbing experience” about five years ago that prompted her to develop the seminar, which she has taught one other time. Confused that many students in an introductory women’s studies class wrote thoughtful papers but did not speak in class, she pushed them to engage.

“A couple of them said, kind of timidly, ‘well, we talk more in this class than other classes.’ And I just almost lost it.” She was upset, she says, not at them but at the “horrible implications” that students about to declare a major were not sufficiently comfortable to be more than an observer in class.

“Growing Up Girl” considers how young girls’ behavior changes drastically over the course of adolescence, when they “have to become women,” Beauboeuf says. “It’s not a biological process simply … It’s about being perceived as not a girl anymore and being expected to behave like a woman. That’s a very different and much more constrained status. I’ve always been interested in what comes before – the identity, the person that women know themselves to have been before they had to become women.”

The class, she says, “is not about making women more into girls. It’s about opening up possibilities that I think they should have had all along the way. Maybe it’s redefining what it is to be a woman. Maybe it’s redefining what it is to be a person.”

Lily Rakow, a first-year student from Maryland, says she chose the seminar because “I just thought it was really interesting to look at how girls grow up and how society influences our upbringing and how we turn out. … Some guys just really don’t understand where girls come from and the ways in which we can feel oppressed sometimes, and that’s important to talk about in this class.”

My goal isn’t necessarily to change them but to get them to see there’s a different way of understanding this topic, of seeing this world.– Matthew Oware, Lester Martin Jones professor of sociology

The “Man Up” seminar appealed to Amelia Mauldin, a first-year student who attended an all-girl high school in St. Louis, because “I don’t know a ton about masculinity … I know there’s not just a one-size-fits-all kind of answer for it and I think also the conversation around topics like masculinity, femininity, gender and self-expression is just totally changing, especially recently. There’s a lot of new words that are being introduced and new meanings being assigned to words we already have.”

In “Man Up,” Oware, the Lester Martin Jones professor of sociology, intentionally muddles up the traditional view of manhood. At the beginning of the seminar, which he also has taught as a 200-level course and a winter term, he asks students what it means to be a man. They “tend to say the same things – being strong, being a provider, being tough, being not vulnerable,” he says. “So what I attempt to do – I mean, it’s in the title – is unpack those notions and to some degree complicate our ideas of what it means to be a man in our society to get students to move beyond the things they typically hear.”

The seminar’s title is a gimmick, he says, intended to entice students who might think that the course will reinforce their traditional views. “For the first couple of weeks, the straight male students and straight female students are sort of a bit disoriented, but that’s the whole point – to disorient them,” Oware says. “I want them to be muddied and confused. That’s the point of the class and essentially that’s the point of college.”

The class has changed some students, who recognize “that it’s OK not to be like this dominant model and, as a matter of fact, that dominant model itself is limiting,” he says. “The idea that men can’t express themselves – that is limiting to us. The idea that men can’t show a wide range of emotions – that’s limiting.”

But “if they don’t necessarily get it or fully grasp it at the end of the semester, that’s OK,” Oware says. “For me, the important part is they’ve been introduced to information that’s contrary or at least complicates what they’ve heard their previous 18 years. That’s the important part – that they got some countervailing information that says it’s OK to think about this in a different way. My goal isn’t necessarily to change them but to get them to see there’s a different way of understanding this topic, of seeing this world.”

Browse other stories

-

Athletics

-

Women's Golf - Williams Selected Academic All-America®

-

Football - DePauw-Record 190 Student-Athletes Named to NCAC's Dr. Gordon Collins Scholar-Athlete Honor Roll

-

Football - 336 Students Named to 2025 Spring Tiger Pride Honor Roll

More Athletics

-

-

News

-

Outstanding scholars named to Spring 2025 Dean's List

-

Alumni News Roundup - June 6, 2025

-

Transition and Transformation: Inside the First-Year Experience

More News

-

-

People & Profiles

-

11 alums make list of influential Hoosiers

-

DePauw welcomes Dr. Manal Shalaby as Fulbright Scholar-in-Residence

-

DePauw Names New Vice President for Communications and Strategy and Chief of Staff

More People & Profiles

-

-

Have a story idea?

Whether we are writing about the intellectual challenge of our classrooms, a campus life that builds leadership, incredible faculty achievements or the seemingly endless stories of alumni success, we think DePauw has some fun stories to tell.

-

Communications & Marketing

101 E. Seminary St.

Greencastle, IN, 46135-0037

communicate@depauw.eduNews and Media

-

News media: For help with a story, contact:

Bob Weaver, Senior Director of Communications.

bobweaver@depauw.edu.