The United States has the highest rate of imprisonment in the world, 716 per 100,000 residents, and Americans spend $270 billion a year to keep 2.2 million of their fellow citizens locked up. Congress undertook criminal justice reform last year, passing the First Step Act with bipartisan support. Bordt, a DePauw sociology professor, has researched the sociology of punishment. We asked her:

Why does the U.S. imprison so many of its citizens? Should state and federal government leaders do more to address mass incarceration?

Many assume that our country’s high imprisonment rate is a result of a high crime rate. But incarceration rates and crime rates move independently of each other. In the past 40 years the incarceration rate has more than quadrupled as the crime rate has steadily decreased. Any discussion of mass incarceration must be decoupled from crime; something else is driving imprisonment rates.

To understand what that is, we need an updated conceptualization of prisons. When I started studying prisons 35 years ago, it was standard to think of prisons as autonomous units loosely aggregated by state or a federal system. Today prisons are situated in a vast network linking corporations, government, correctional communities and media – the prison industrial complex. Identifying the economic, political and social interests embedded in this complex reveals why we have mass incarceration, why it is so resilient and why it is unlikely to reverse direction.

Mass incarceration is profitable: CoreCivic and the GEO Group Inc. run private prisons and have government contracts with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, U.S. Marshall Service and Federal Bureau of Prisons, among others. State-run prisons outsource most services, such as health care, food and telephone services, to private companies. Corporations “employ” prisoners to make their products or carry out services (e.g., Target, Honeywell, Microsoft, Revlon), paying them literally pennies for their labor. If you are in the prison business, more incarcerated bodies represent more profit, a hallmark of capitalism.

Mass incarceration reinforces our government’s neoliberal public policy:Central to neoliberal ideology and policy is the privatization of public services. The American Legislative Exchange Council, at the behest of its corporate funders, writes and lobbies for “model” legislation such as the “Truth in Sentencing Act” and the “Three-Strikes-You’re-Out Act,” both of which fuel mass imprisonment.

Mass incarceration is consistent with our racial order that criminalizes skin color, immigration and poverty: Scholars argue that mass imprisonment is the latest in a long line of systems that legitimize white supremacy: first slavery, then convict leasing, next Jim Crow and now mass incarceration. Others include other dispossessed groups: Latinx, immigrants and poor whites. Racism, in various iterations, fuels who makes up the mass in mass incarceration.

So should federal and state government leaders do more to address mass incarceration? Should we applaud the First Step Act? Yes and no. It is hard to argue against justice reinvestment, aiding prisoners with reentry and reducing recidivism. But none of these actions will put a dent in the structural forces that ensure the tenacity of mass imprisonment. The prison industrial complex does not just encapsulate prisoners. It envelops those of us in the free world as well. We are all implicated in mass incarceration – by the products we consume, the corporations that employ us, the politics we preach. So it will take us all in nothing short of a mass movement to begin to chip away at it.

The Bo(u)lder Question

is a regular feature of DePauw Magazine, which is published three times a year.

DePauw Magazine

Spring 2020

Leaders the World Needs: Alum who attended college against odds guides youths to do same

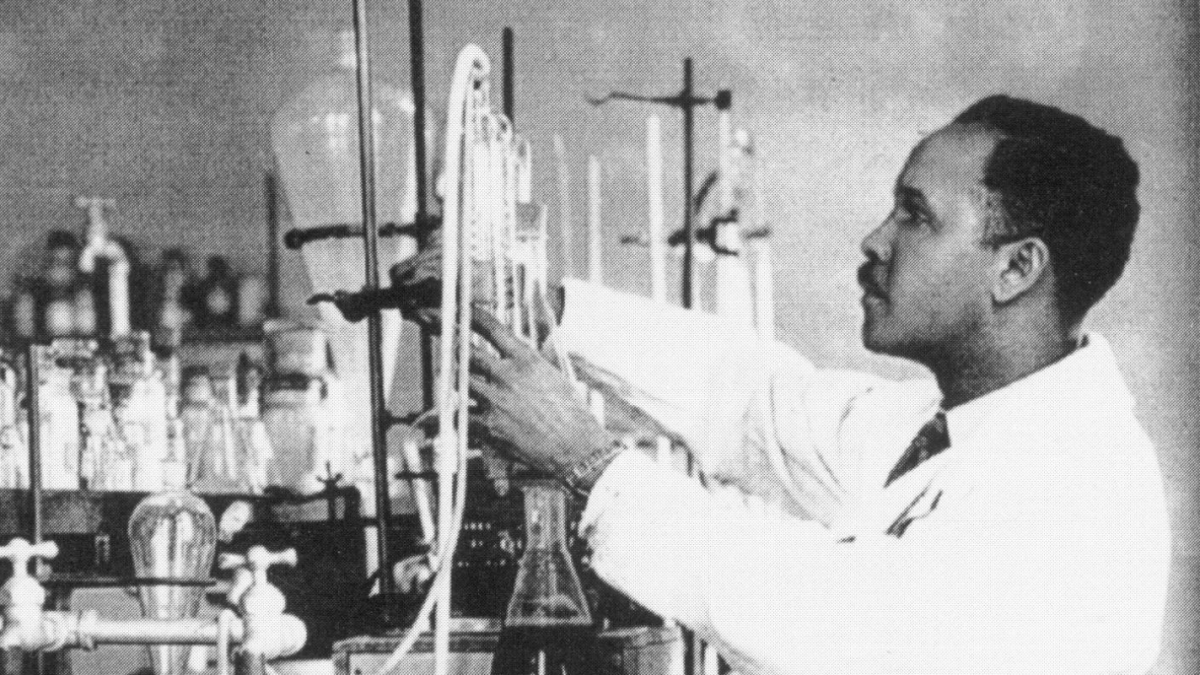

Leaders the World Needs: Alum who attended college against odds guides youths to do same OLD GOLD: Percy Julian, unappreciated in his time, inspires today

OLD GOLD: Percy Julian, unappreciated in his time, inspires today FIRST PERSON with Jonna McGinley Reilly '00

FIRST PERSON with Jonna McGinley Reilly '00  The Bo(u)lder Question By Rebecca Bordt

The Bo(u)lder Question By Rebecca Bordt The poet

The poet The iceman

The iceman The most American athlete ever

The most American athlete ever

The beekeeper

The beekeeper The juggler

The juggler The lucky guy

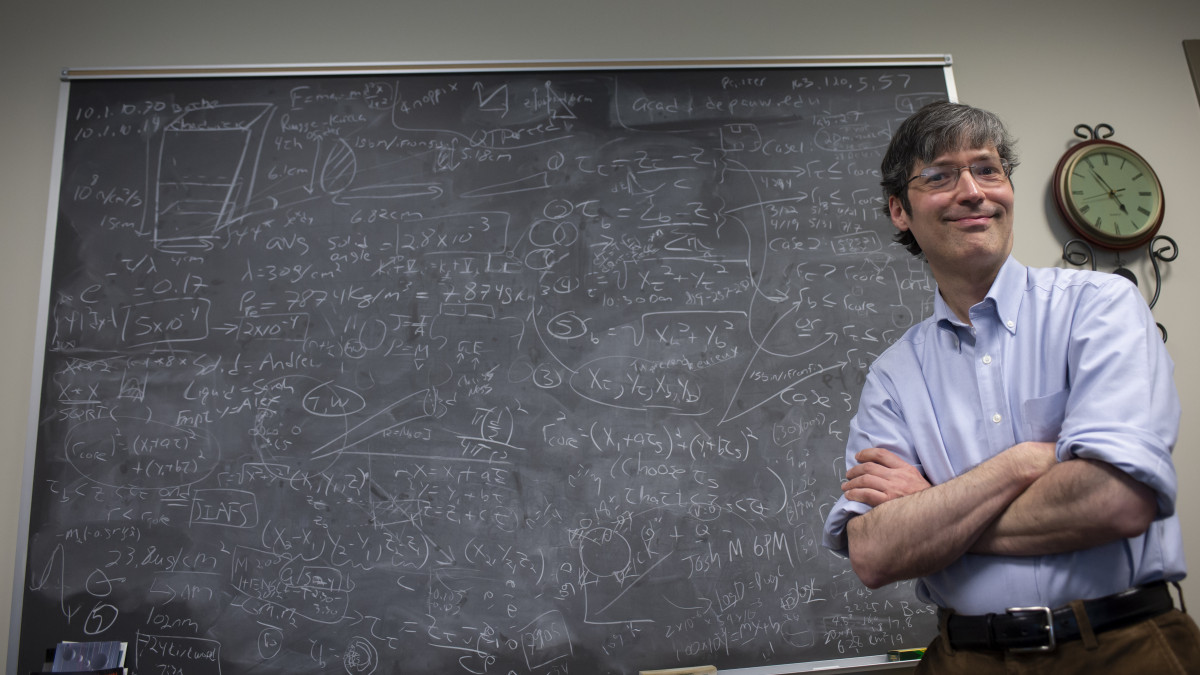

The lucky guy Aligned stars: Snowshoeing scientist studies the skies

Aligned stars: Snowshoeing scientist studies the skies Indelible images: Devastating photo, desperate need move alums to act

Indelible images: Devastating photo, desperate need move alums to act The nonconformists

The nonconformists A twist of fate: Unexpected discovery rekindles family legacy

A twist of fate: Unexpected discovery rekindles family legacy

DePauw Stories

A GATHERING PLACE FOR STORYTELLING ABOUT DEPAUW UNIVERSITY

Browse other stories

-

Athletics

-

Women's Golf - Williams Selected Academic All-America®

-

Football - DePauw-Record 190 Student-Athletes Named to NCAC's Dr. Gordon Collins Scholar-Athlete Honor Roll

-

Football - 336 Students Named to 2025 Spring Tiger Pride Honor Roll

More Athletics

-

-

News

-

Outstanding scholars named to Spring 2025 Dean's List

-

Alumni News Roundup - June 6, 2025

-

Transition and Transformation: Inside the First-Year Experience

More News

-

-

People & Profiles

-

11 alums make list of influential Hoosiers

-

DePauw welcomes Dr. Manal Shalaby as Fulbright Scholar-in-Residence

-

DePauw Names New Vice President for Communications and Strategy and Chief of Staff

More People & Profiles

-

-

Have a story idea?

Whether we are writing about the intellectual challenge of our classrooms, a campus life that builds leadership, incredible faculty achievements or the seemingly endless stories of alumni success, we think DePauw has some fun stories to tell.

-

Communications & Marketing

101 E. Seminary St.

Greencastle, IN, 46135-0037

communicate@depauw.eduNews and Media

-

News media: For help with a story, contact:

Bob Weaver, Senior Director of Communications.

bobweaver@depauw.edu.