Sharon Crary was on the frontlines battling the deadly Ebola hemorrhagic fever, working in a country terrorized by a resistance leader who maintained power by amputating enemies’ noses, lips, ears and arms.

And yet the lasting impression that she took away from her first visit to Uganda was how much she loved the people and how much she wanted to do what she could to improve their lives.

“Somehow,” she said, “I really fell in love with it there.”

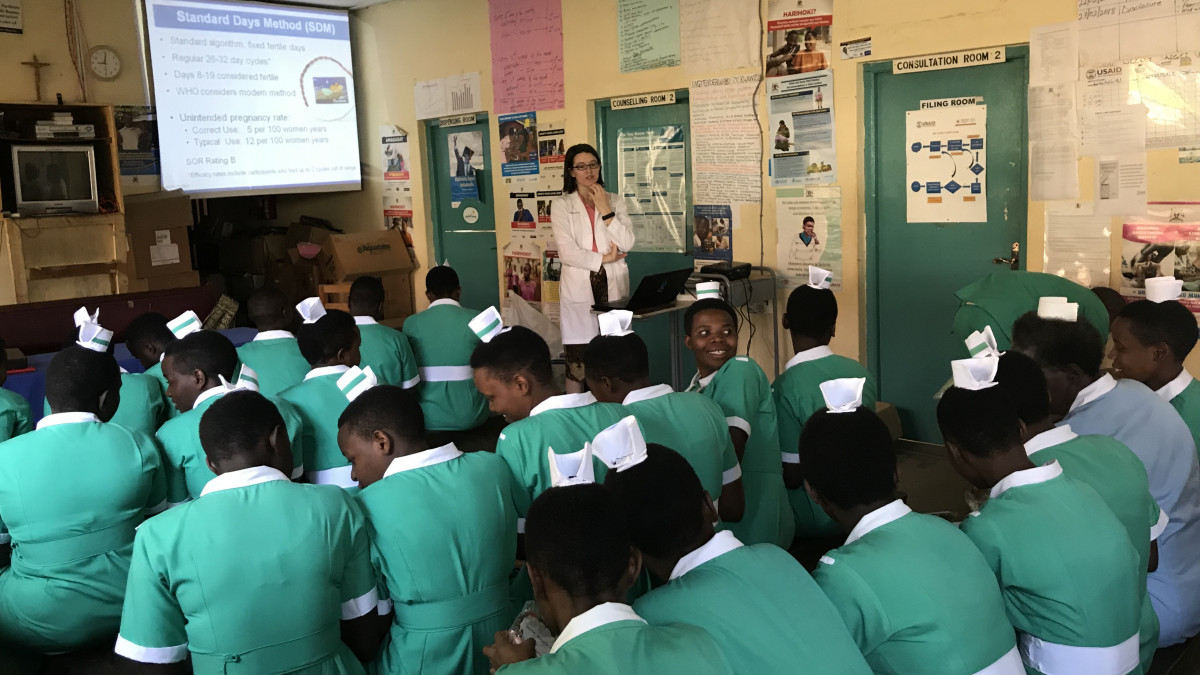

Crary, a professor of chemistry and biochemistry and co-director of DePauw’s Global Health Program, is both a research scientist and a humanitarian. She loves working in a laboratory but found her humanitarianism reinvigorated when she went to Uganda in late 2000 on behalf of the Centers for Disease Control.

Crary, a professor of chemistry and biochemistry and co-director of DePauw’s Global Health Program, is both a research scientist and a humanitarian. She loves working in a laboratory but found her humanitarianism reinvigorated when she went to Uganda in late 2000 on behalf of the Centers for Disease Control.

She had attended a Quaker high school that required its students to engage in service activities and write about them. But “that went away from me for a little while in college … (when) I got really focused on science,” she said. “Everything was just science and lab, and I think going to Uganda reopened that world for me, that there are people who are living in much more dire circumstances than me, through no fault of their own, and I can do something to change that.”

As a CDC researcher, she never expected to go into the field. But then a boss asked her if she would be willing to spell a colleague who had been toiling in the Ugandan outbreak of Ebola so that person could spend Christmas with a young daughter.

“I remember just being shocked,” she said. And scared – not of the deadly illness nor of traveling to a country unknown to her, but rather of the spiders and cockroaches she might encounter.

“I had the silliest fears, you know? Then within a couple weeks of being there, I definitely put those fears to rest,” she said. “There are other things that matter in life, like the people who are living on mud floors.”

For six weeks, she conducted testing that required her to wait several hours for the results. She would use those free hours to drive a borrowed car to St. Jude Children’s Home, an orphanage, “and hang out with kids there.” She felt safe on the journey along deserted roads, she said, because Ebola had scared people – including the resistance fighters – inside.

“What I care about is I’m training students to think really well about research and to learn techniques very well and to be able to analyze data and critique their own experiments so, whatever they do next, I know they’re going to do it very well.”– Sharon Crary

All these years later, thanks to Social Promise, an organization Crary founded her first year back home and incorporated as a nonprofit in 2011, the hospital now has a primary school on site and a center that seeks to dispel folklore that children with disabilities are all-too-public proof that the parent has done something wrong; it also teaches parents to cope with their children’s disabilities. St. Mary’s Lacor Hospital, where Crary worked during her CDC stint, also has benefited from her organization’s fundraising.

Social Promise also offers programs focused on teaching young children about life in rural Uganda and urging them to use their creativity to problem-solve. The programs also teach about philanthropy; “there’s a lot of science,” Crary said, “that shows that giving and helping others makes you feel good. … Having empathy for people has that same effect, so we try to teach about empathy.”

Meanwhile, Crary still gets into the lab, but it is with DePauw student researchers or, as she was doing before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, helping high school students complete a science fair project. Doing so, she said, “reminds me how nice it is to be in lab and how peaceful and calm it is. It’s really rejuvenating to me.”

She still works with one small – and nonthreatening – piece of the Ebola virus, but the goal isn’t to find a treatment; that’s not realistic in a lab where a rotating group of undergraduate students work just a few hours each week. “My goal is to train my students to do research,” she said. “I actually don’t even care anymore about that long-term goal. It’s just irrelevant to me, really. Oddly. What I care about is I’m training students to think really well about research and to learn techniques very well and to be able to analyze data and critique their own experiments so, whatever they do next, I know they’re going to do it very well.”

DePauw’s global health program

As best as Sharon Crary can remember, she and Rebecca Upton were at a basketball game when they started talking about a global health major at DePauw.

“For me, seeing the situation in Uganda when I was 30 years old made me realize I wish I had learned about it sooner,” Crary said. “... I went to a liberal arts college also, and I thought it’s really a liberal arts discipline because it requires math skills, logic skills, scientific skills, communication skills. Some empathy skills. Things we really stress, particularly here at DePauw.”

Crary and Upton, a professor of sociology and anthropology and previously a medical anthropologist who worked in women’s health and HIV/AIDS, got serious about writing a proposal after Upton, who already had a Ph.D., earned a master’s in public health in 2014.

“Global health has always been one of the clearest examples of the strengths of the liberal arts,” Upton said. “As Sharon and I have always said, it is inherently interdisciplinary – an applied discipline that requires students to be facile (and) fluent in both the sciences and social sciences.”

The faculty accepted their proposal and the two were named co-directors of the global health program. The first cohort of five majors graduated in 2018, followed by 22 majors in 2019 and 20 this year.

Though many students are inspired to study global health because of their study-abroad experiences, others want to delve into questions of access to health care locally, Crary said. “It’s the same question you have with access to a doctor in rural Uganda, but there might be different root problems and different solutions.”

DePauw Magazine

Summer 2020

The Bo(u)lder Question

The Bo(u)lder Question  Retired archivist reflects on 36 years as DePauw’s memory keeper

Retired archivist reflects on 36 years as DePauw’s memory keeper First Person by Connie Campbell Berry '67

First Person by Connie Campbell Berry '67 First Person by Wayne Glausser

First Person by Wayne Glausser Battling an epidemic, treating individuals: Physician alum has done it all

Battling an epidemic, treating individuals: Physician alum has done it all  Welcome, Class of 2024!

Welcome, Class of 2024! She has loved them since she was 6: vet cares for, competes with and rescues horses

She has loved them since she was 6: vet cares for, competes with and rescues horses Liberal arts taught wildlife vet to consider different approaches to patients’ problems

Liberal arts taught wildlife vet to consider different approaches to patients’ problems Scientist and humanitarian: Prof embodies disparate interests, then acts on and teaches them

Scientist and humanitarian: Prof embodies disparate interests, then acts on and teaches them Researcher follows the science toward treatments

Researcher follows the science toward treatments The ‘dura mater’ handles medical training and motherhood with aplomb

The ‘dura mater’ handles medical training and motherhood with aplomb  Evolving interests drive ’12 grad to trade test tubes for a stethoscope

Evolving interests drive ’12 grad to trade test tubes for a stethoscope Alum hopes to meet global needs by establishing med school

Alum hopes to meet global needs by establishing med school The healers

The healers Personal experiences prepared ’76 alum for work, service

Personal experiences prepared ’76 alum for work, service DePauw in the time of COVID-19

DePauw in the time of COVID-19 DePauw’s new president: A ‘visionary,’ empathetic and focused optimist ... who sings

DePauw’s new president: A ‘visionary,’ empathetic and focused optimist ... who sings

DePauw Stories

A GATHERING PLACE FOR STORYTELLING ABOUT DEPAUW UNIVERSITY

Browse other stories

-

Athletics

-

Football - DePauw-Record 190 Student-Athletes Named to NCAC's Dr. Gordon Collins Scholar-Athlete Honor Roll

-

Football - 336 Students Named to 2025 Spring Tiger Pride Honor Roll

-

Football - DePauw Unveils 2025 Athletics Hall of Fame Class

More Athletics

-

-

News

-

Outstanding scholars named to Spring 2025 Dean's List

-

Alumni News Roundup - June 6, 2025

-

Transition and Transformation: Inside the First-Year Experience

More News

-

-

People & Profiles

-

11 alums make list of influential Hoosiers

-

DePauw welcomes Dr. Manal Shalaby as Fulbright Scholar-in-Residence

-

DePauw Names New Vice President for Communications and Strategy and Chief of Staff

More People & Profiles

-

-

Have a story idea?

Whether we are writing about the intellectual challenge of our classrooms, a campus life that builds leadership, incredible faculty achievements or the seemingly endless stories of alumni success, we think DePauw has some fun stories to tell.

-

Communications & Marketing

101 E. Seminary St.

Greencastle, IN, 46135-0037

communicate@depauw.eduNews and Media

-

News media: For help with a story, contact:

Bob Weaver, Senior Director of Communications.

bobweaver@depauw.edu.