Welcome to the VIRTUAL EXHIBIT of

Shifting Gaze: A Reconstruction of The Black & Hispanic Body

Contemporary Art from the Collection of Dr. Robert B. Feldman

March 1 - June 20, 2021

Peeler Art Center, Lower Gallery

Scroll for artwork.

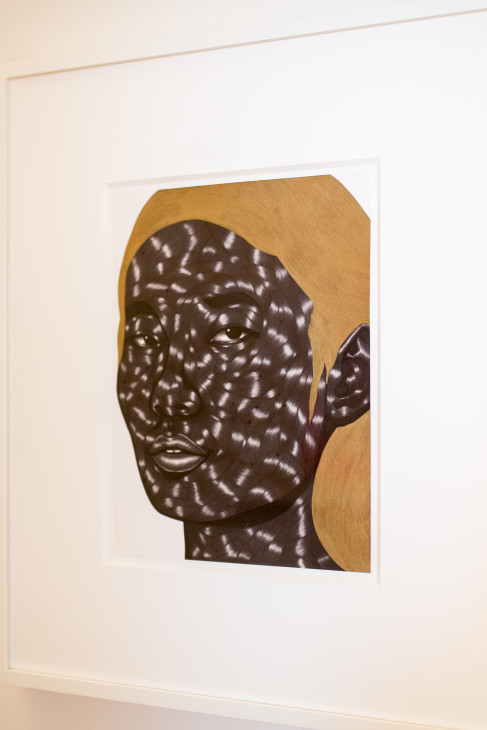

Mickalene Thomas

Mickalene Thomas Mickalene Thomas

(b. Camden, New Jersey 1971)

Lives and works in New York, NY

I’m not the Woman You Think I am, 2010, rhinestones, acrylic, and enamel on wood panel

Collection of Dr. Robert B. Feldman

Mining art history, popular culture, and the black power movement of the 1970s, Mickalene Thomas creates dazzling, sensual, and palpably confidant portraits that reconstruct multiple mythologies about black sexuality and black feminine power that shifts the gaze with immediacy, throwing charged relationships between sitter, artist, and the viewer off its preconceived historic context. The figure, classically composed as 19th-century odalisque (reclining nude) owns her space and how she is viewed as she coolly confronts the viewers directly with her gaze, as if in dialog. She dismantles stereotypes and cultural imperialism, with an Afro-humanism inspired by the 1970s Black Power movement alongside a desire to declare beauty on her own terms. Also, akin to the Pattern and Decoration movement of the 1970s, her seriously ornamental beads, rhinestones, glitter, and use of craft and domestic elements add to the decorated pastiche of the collaged surface, resulting in a tactile material bling that speaks of abundance, pride, sensuality, and ownership. Inspired by formidable women in her own life, most significantly her mother, a model and homemaker, Thomas brings strength and courage to her reclining figure that yields a nuanced sense of collaboration that breaks another cultural barrier in who is looking at who, who is subservient here—no one. This ownership radically conflates art history, black and white feminism, with political history and notions of power, without modesty and without apology, but with a refreshing and heightened sense of joy.

Jamel Shabazz

Jamel Shabazz Jamel Shabazz

(b. Brooklyn, New York 1960)

Lives and works in New York, NY

Fly Girls (1/9), 1982, photograph

Collection of Dr. Robert B. Feldman

Great photography captures the spirit of the times and places you right in the middle of an experience. —Fred Brathwaite aka FAB 5 FREDDY

Jamel Shabazz became interested in photography as a teen and by the 1970s was intensely inspired by what was going on around him in his immediate environment in Brooklyn during a period of immense change. He has powerfully documented the culture and urban life of African Americans for over thirty years. Growing up in the projects of Red Hook during the turbulent 1960s, shaped by the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement, Shabazz became fascinated by the images that inundated society through print and on TV. His introduction to the developments of 1970s, including Disco, Rhyming, Rapping, and the gangs and guns that came with it led Shabazz to set out to record what he termed the “Resurrection” of the 1980s, to include fashion, style, attitude, and positive images of the ‘cool,’ especially among the youth. He documented the generation that gave birth to hip-hop, “not only the most dominant and inclusive youth culture in history but also the most stylishly innovative and consistently advanced generation since the rock ‘n roll era.” Only one decade later, this work would also include those affected by the crack and AIDS epidemics. His eye was on the street, he knew the street and was trusted. Here, these young women represent a newly rising confidence in black women that manifest in posture, the gaze, and in fashion. His hundreds of images of Brooklyn’s youth are the subject of several books. His image capturing was instantaneous, intuitive, and fast, like the great photographer William Eggleston, Shabazz knew his material and his subject when he came upon it, and rarely did he take an image twice.

Paul Henry Ramirez

Paul Henry Ramirez Paul Henry Ramirez

(b. El Paso, Texas 1963)

Lives and works in New York, NY

Untitled I (Eccentric Stimuli Series), 2014, acrylic and flashe on paper

Collection of Dr. Robert B. Feldman

Paul Henry Ramirez creates what he terms biogeomorphic abstractions, or “a fusion of biomorphic and geometric forms” that combines smooth, shiny, delicately curving line-work with brightly colored bold forms that culminate in sensual dances. His figural-based abstractions, he coined Playconics for their playful and energetic interaction, resound off forms as if stimulated by the form itself. The curvilinear lines, with pops of color bursts, carry the weightless bulbous shapes with fabulous drips and splatters that reference the male and female body or intersections of movement between bodies. Often a collaborator with dancers and choreographers, Ramirez hones in on the grace of physical movement through the air, reduced beautifully with line, color and form here. With light gestures, the anthropomorphized forms swirl in joy, as a personification of the simplest human references, in exclamations of joy and sensuality. As a distilled Latin Baroque poem or Rocco desire, non-alphabetical and non-figurative, Ramirez whispers exchange in space with sensuality outside any representation or figurative narrative.

Samuel Levi Jones

Samuel Levi Jones Samuel Levi Jones

(b. Marion, Indiana 1978)

Lives and works in New York, NY

Love is Complicated, 2016, deconstructed encyclopedias, lawbooks, and African American reference books on canvas

Collection of Dr. Robert B. Feldman

Comprised of the torn, mangled and ripped shells of antiquated manuscripts, Love is Complicated forms a restitched crafted collage of quilt-like construction from the leather coverings of earlier accepted tomes of knowledge. Samuel Levi Jones investigates how power structures are formed, questions who observes, writes, and defines whose histories are taught and how those ideas change as society shapes them. Only two book titles are legible, the first, Ethnicity in the United States, is clearly visible while another, The Book of Knowledge Annual is inversed forcing a change in perspective to read the piece. As the viewer we are not able to know what was once contained within those pages but we can judge the book by its cover—and equally by its erasure— to explore our understanding as to what it might contain, and dually consider how ethnicity, culture, and history are perceived and or constructed, and here, de-constructed and re-constructed, conflating the past and a ubiquitous present. The body is implied here through the act of the erasure; removing the content and power of how we gain knowledge. By physically, and aggressively dismantling pages from the spinal structure of a book, the act of learning comes into question and past ideas can be rejected and reassessed based on new knowledge and new perspectives.

Titus Kaphar

Titus Kaphar Titus Kaphar

(b. Kalamazoo, Michigan, 1976)

Lives and works in New Haven, CT

Columbus Day Painting, 2014, mixed media on canvas,

Titus Kaphar is an artist whose paintings, sculptures, and installations examine the history of representation by transforming its styles and mediums with formal innovations to emphasize the physicality and dimensionality of the canvas and materials themselves. His practice seeks to dislodge history from its status as the “past” in order to unearth its contemporary relevance. He cuts, crumples, shrouds, shreds, stitches, tars, twists, binds, erases, breaks, tears, and turns the paintings and sculptures he creates, reconfiguring them into works that reveal unspoken truths about the nature of history. Open areas become active absences; walls enter into the portraits; stretcher bars are exposed; and structures that are typically invisible underneath, behind, or inside the canvas are laid bare to reveal the interiors of the work. In so doing, Kaphar’s aim is to reveal something of what has been lost and to investigate the power of a rewritten history.

Clotilde Jimenez

Clotilde Jimenez Clotilde Jiménez

(b. b. Honolulu, Hawaii 1990)

Lives and works in London, UK

Fruity Boys, 2016, mixed media on paper

Collection of Dr. Robert B. Feldman

Clotilde Jiménez creates idiosyncratic narratives, with common materials, that are both subjective while politically far-reaching in an effort to create images of unified beings beautifully made of many disparate parts. His work looks beyond binary terms to explore broader and more inclusive ways of looking at the Black, Hispanic, and Hawaiian Archipelago, Island body. The title, Fruity Boys signifies seemingly harmless and funny, yet derogatory designation about male children who dress in wild, flamboyant, or ridiculous outfits that may cause one to question their own sexuality as they get older. The three “Fruity Boys” are playfully hanging out in suburbia, imagining breasts of island coconuts, bikinis, Hawaiian Hula Leilani gesturing, the mischievous nature of childhood innocence and sexual exploration. The boundary-pushing unfolds on stage before the quintessential symbol of American domestic happiness, the white picket fence, as the figures folly and fumble toward the attainable homogenized American dream, a ubiquitous site for unpacking contradictions. Fruity Boys is part of a large series, in which Jiménez portrays boys frolicking in pursuit of something beyond, as the perceived marginalized childlike imagery make ridiculous certain boundaries of race, gender, and sexuality. The absurd is exemplified in the use of everyday materials, particularly found magazine images, and is effective in Jiménez’s work with a powerful nod to Dadaism, especially the brilliant and poignant collages of Hannah Höch, the original photomontage artist who’s shifting ideas about gender roles, queerness, and androgyny resonate here. He reconstructs the black body as not fixed, in a parody of popular culture and racist stereotypes, and in ownership of full-blown satire and wit as the gaze, his lens, powerfully focuses and follows you, the looker.

Farley Aguilar

Farley Aguilar Farley Aguilar

(b. Managua, Nicaragua 1981)

Lives and works in Miami, FL

The Night of Broken Glass, 2015, oil on linen

Collection of Dr. Robert B. Feldman

Of his work, Farley Aguilar says “I depict my feeling of how history, the past, filters through time and influences the fear and injustices we must deal with in our everyday lives." Mining historic photographs, Aguilar considers what dark complexities may happen in the image, how social issues of the past merge and reappear within the present. In The Night of Broken Glass, Aguilar depicts a group of five figures standing before a storefront, their features—from their eyes and ears to skin color—are exaggerated and mask-like. A black caricature is in the upper left hand of the window and an insult is inscribed at the top of the canvas, the building from which they emerge, as well as on the forehead of the figure closest to the shop. The title is evocative of the 1938 Kristallnacht that took place under the government of Nazi Germany, a devastating night of assault and the destruction of Jewish-owned stores, buildings, and synagogues, which was marked by a littering of broken glass throughout the streets. The event is considered now to be foreshadowing of the Holocaust to come and thus the painting alludes to how this past is concurrent with the everyday lives of people of color, and other marginalized groups.

Jennie C. Jones

Jennie C. Jones Jennie C. Jones

(b. Cincinnati, Ohio1968)

Lives and works in New York, NY

Five Point One Surround (15/15), 2014, set of 5 intaglios, on paper

Collection of Dr. Robert B. Feldman

Jennie C. Jones’s set of five intaglio prints reference her audio collages, minimalist paintings, and sound sculptures that explore the formal and conceptual intervals between modernist abstraction and black avant-garde music, particularly American jazz. Her sparse compositions work to integrate sight and sound. Jones explores how sound and culture, as located in music, are contained and shared as well as how certain music and material culture are absent from modernist history and museums, specifically the contributions made by African American artists in the 1950s and 1960s. Motivated by the gap in this American modernist story and inspired by artists such as John Coltrane, Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday, Miles Davis, and other African Americans whose contributions to modernism are significant but overlooked, inspired her term “listening as a conceptual practice.” Her reductive speakers here imply sound, resonance, sonic energy, and denote that the viewer is listening while conjuring movement across a musical score where silence (white) is as important as sound (black), with a single cutting edge in red as amplification. In this way, Jones bridges abstraction and minimalism with modes of conceptualism that moves towards a filmic, hard-edge graphic score, connecting how sound functions in a visual context. The musical speaker serves as a moving metaphor for how we hear, hold, augment, absorb, and even distort things.

Wanda Ralmundi-Ortiz

Wanda Ralmundi-Ortiz Wanda Raimundi-Ortiz

(b. Bronx, New York 1973)

Lives and works in Orlando, FL

Bargain Basement Sovereign (Reinas/Queen Series), (2/5), 2015, photograph, performance still

Collection of Dr. Robert B. Feldman

Wanda Raimundi-Ortiz is interested in the marginalized “other” and the objectification that often comes with framing meaning and defining signifiers, particularly for Latinx women balancing binary expectations: being brown, black, Puerto Rican, American, female, colonial and foreign. This piece works at the crossroads of identity and visibility, claiming value through presence in a world where women of color’s experiences can be rendered invisible, or less than. Her self-portraits and associated performances are based on a series of archetypal characters created to take on roles: actual, exaggerated stereotypes, and fictional that distance the self from that reality in healing or defense. In her narrative portrayal of Bargain Basement Sovereign (Reinas, Queen Series), Raimundi-Ortiz is transformed into royalty, of a different color, here summoning the highs and lows of every day, the banal, the dismissed, the disparaged, and injured in a psychic state of otherness. In part, biographical, but universal regarding ideas about overcoming. Raimundi-Ortiz considers the cruelty of objectification and the diminishing behavior that cheapens women, relegates one as a bargain, deemed not worthy. The Queen is confrontational, Raimundi-Ortiz reconstructs the iconic image of the female body of color from multiple intersecting perspectives: colonial imperialism, the Latin Diaspora, first generation Bronx Nuyorican, feminism, activism, and motherhood. She is peeling back multiple layers of social, cultural and political realities that resonate in contemporary discourse as she examines notions of beauty, sexuality, maternity and how each is entwined with women’s roles and power in society. In light of current identity politics and the erasure of women, Raimundi-Ortiz’s queen is present, owning her monarchy.

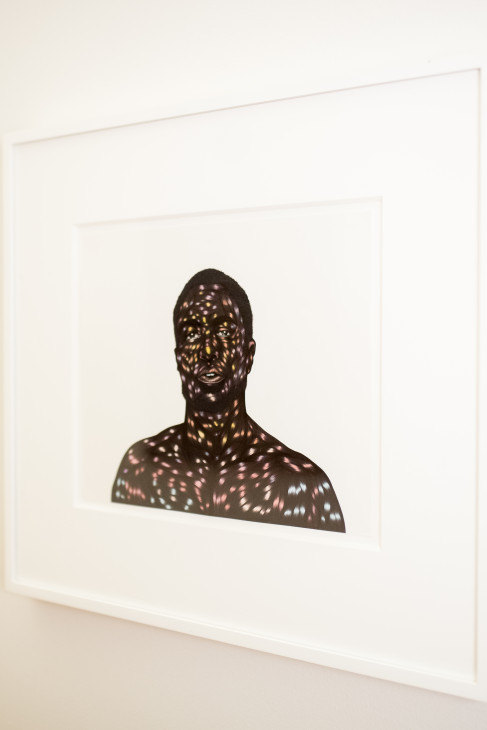

Nathaniel Donnett

Nathaniel Donnett Nathaniel Donnett

(b. Houston, Texas, 1968)

Lives and works in Houston, TX

Reflect 6, 2014, mixed media on paper bags

Collection of Dr. Robert B. Feldman

My work is rooted in Dark Imaginarence, a term I have coined that conceptually and formally ties together social critique, the poetics of the everyday, and African American creative cultural expression. It is a polyrhythmic or interdisciplinary working and poverty class approach to art-making and culture producing, or perhaps culture investigation situated in the African American experience and imagination. —Nathaniel Donnett

Nathaniel Donnett’s artworks span multiple media as he intuitively investigates human behavior in memory, now, and the future. He is interested in how certain social and political beliefs implemented throughout history and into the future have shaped and will continue to shape the psychosocial acclimatization of oneself as well as their greater social environment. In Reflect 6, the silhouetted figure of a black woman holds up a mirror to her face, her head and hair constructed of textured, melted black plastic bags, igniting painful notions of trash and discard. As the figure pauses to reflect in the present she sees a blank, red face reflected, warning and anger emerge but also remembrance, a space between action and reflection. Her body is sewn into and painted on to a backdrop of paper bags, a reference and critique to the brown paper bag tests administered during the 20th century in the United States by some African American institutions. The practice prized lightness in skin tone, closer to or lighter than that of the brown bag over darker skin tone, enforcing a western idealized standard of beauty onto a community of diverse peoples forcibly brought to the United States, a practice and mythology that led to racism within the black community itself. While these notions are no longer overtly enforced through the test, they can still be buried and expressed in destabilizing ways in popular culture but are here and have instead been undermined and removed of power by African American cultural movements such as the 1960s “Black is Beautiful” and contemporary #BlackGirlMagic, celebrating the beauty, power, and resilience of blackness, especially for women.